Lessons from history on low-rate environments

Schroders study compares effect of low interest rates on equities markets in US, UK and Japan in the last century

Singapore

THE current prolonged low-interest-rate environment has been cause for concern for equity investors. But, according to Schroder Investment Management in Singapore (Schroders), history has witnessed this phenomenon before.

And it can, to an extent, teach us how our equity markets will behave now.

In its latest Talking Point report, Schroders' head of research and analytics, Duncan Lamont, examined the historical impact of low interest rates on equity markets.

He said that, while the world has been living with low rates for eight years now, such periods are not new: both the United States and the United Kingdom had rates below one per cent for most of the two decades spanning World War II, while Japan has been living with sub-one per cent rates since 1995.

"Stock markets performed very differently in each case . . . (but) this research argues that the lessons from all three were remarkably similar," he said.

In the US, short-term interest rates averaged less than 0.5 per cent between 1933 and 1950, but equities there delivered an annualised return of 11.6 per cent - or 7.6 per cent a year in real terms.

However, equity markets there were cheap to start with, following the Great Depression; government spending drove high economic growth; and company profits, when compared to the size of the economy, were historically low in 1932.

In contrast, valuations today suggest that US equities are expensive, there is less capacity for an increase in government spending, and profit margins are at historically high levels with far less room for improvement.

The US market currently scores poorly on every single indicator that supported equities between 1933 and 1950. "More challenging times are likely to lie ahead," Mr Lamont said.

Across the Atlantic, the average short-term interest rates in the UK during the same 18-year period were 0.7 per cent. But UK equities generated annual returns of only 5.6 per cent, and with inflation factored in, returns were barely positive.

This difference was due to the fall in UK shares between 1929 and 1932 being more modest, which made the British market more expensive than American equities heading into 1933. The UK's economic performance during and after the war was also relatively worse, and the two World Wars left the UK with a heavy debt burden.

In Japan, interest rates have been low since they were cut to 0.5 per cent in September 1995. Japanese equities have also returned only 1.2 per cent a year, no thanks to economic and corporate governance woes.

What this shows is that a myriad of factors come into play when trying to determine how equity markets will perform in low-rate environments.

"The valuations of equity markets probably remain the most important determinant of performance, but company profits also need to grow. Whether they do is linked to a host of factors, not least government finances and fiscal policy, demographics, the health of the banking sector and inflation.

"And of course, the past performance of markets before is no guide to future returns," Mr Lamont adds.

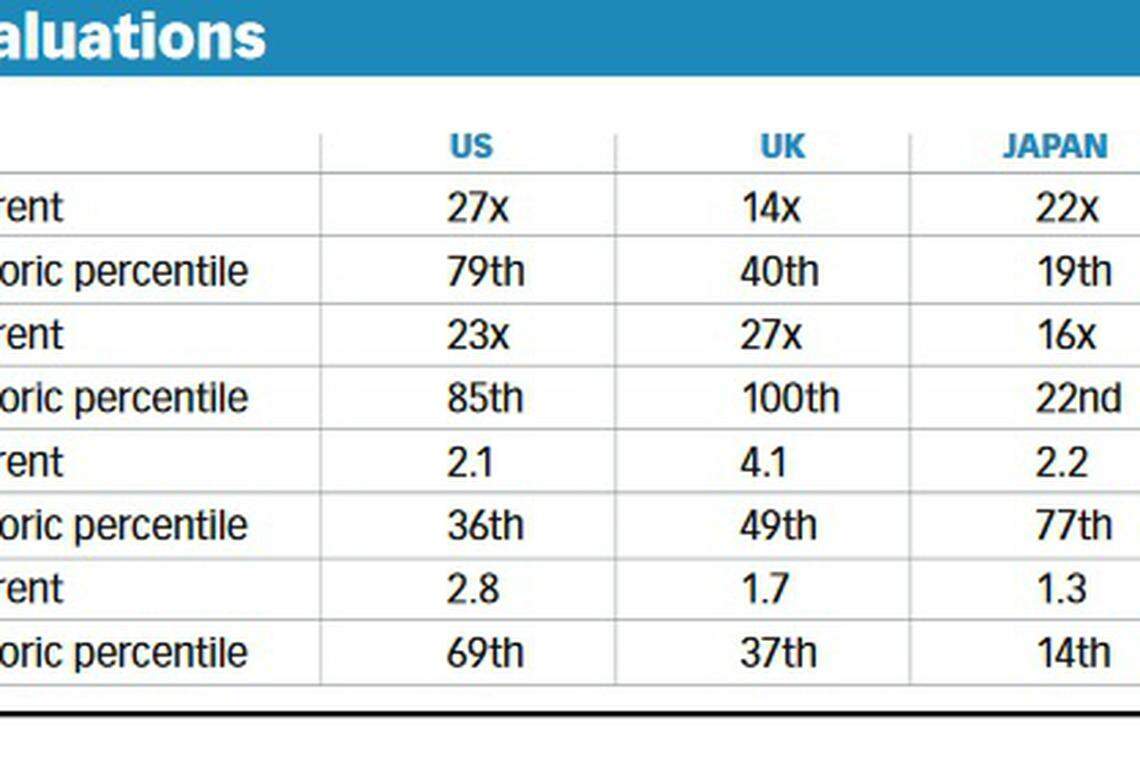

He compared the various markets' CAPE (cyclically adjusted price-to- earnings), P/E (price-to-earnings) and P/B (price-to-book) ratios, and dividend yields today with historic averages. So, for example, the historic percentile for the US CAPE at 79 suggests the market has been cheaper than it is today for 79 per cent of the time.

The US market's high P/E and P/B ratios, compared with historic norms, also show that US equities may be expensive now.

"However, this valuation could be viewed as justified to some extent: the US economy is in better shape than much of the developed world, the banking sector is in reasonable health, core inflation has been running above 2 per cent, and the country has better demographics than elsewhere," he said.

Japanese equities, meanwhile, look reasonable relative to their own history, but less so against other markets.

UK demographics are in better shape, while the country's banking sector is less troubled. But its equity market is dominated by the commodity and financial services sectors, both of which are expected to face structural weakness. A cheap rating on a CAPE basis may be misleading if earnings do turn out to be as low as expected on average over the next economic cycle, Schroders says.

Emerging market equities look cheap, benefit from favourable demographics, healthier government finances, positive inflation and an untroubled banking sector. But growth is expected to remain lower than before and the build-up in Chinese debt is worrying.

Mr Lamont therefore believes no one market stands out as being particularly attractive in these terms.

If global economic growth stabilises or improves, then emerging markets and Japan look best placed, while the highly rated US market may struggle. However, if global growth slows, both emerging markets and Japan, along with Europe, could come under renewed pressure and the US is likely to prove more resilient.

"Investors need to be flexible and ready to seek investment opportunities where evidence of innovation and growth is strongest. (And) though volatility is often viewed in negative terms, investors should also take some comfort in the bumpy ride that Japanese equities have experienced over the past two decades. These conditions, if repeated in this or other markets, should allow skilful investors to add value through timely allocations," Mr Lamont said.

BT is now on Telegram!

For daily updates on weekdays and specially selected content for the weekend. Subscribe to t.me/BizTimes

International

India’s inflation at risk from extreme weather, geopolitical issues: central bank

Thailand to replace military-appointed Senate, reduce its powers

Bankers lose hope of London IPO revival for another year

Decarbonisation schemes are generating hot air

BOJ will hike rates if trend inflation accelerates, says Ueda

India tells spice makers to give details of quality checks after Hong Kong allegations