The robo revolution

With clever software, robo-advisers can put together and maintain a portfolio for the average investor, who might no longer need a flesh-and-blood financial adviser. Is this the way forward?

OW Tai Zhi, co-founder and chief investment officer of AutoWealth, was working for a family office in 2013 when a friend walked in, plonked a S$200,000 cheque on his table, and asked him to invest his money.

"I'd been helping rich people get richer," Mr Ow says. "A lot of friends and family around me kept saying: 'Help us, we are the people who deserve more help'."

Out of that formative experience grew the realisation that perhaps there was something revolutionary he could bring to the asset management table.

There was already a high level of frustration directed against capitalism's standard-bearers: the fund managers who invest our money in unit trusts, the banks and insurers who take a hefty cut for distributing these products, and the wealth advisers who require high minimums.

The solution, for forward-thinkers like Mr Ow, was software. Programmes that professed to offer a better solution for the average investor than the smartly-dressed financial adviser who charged high fees and whose service didn't match up. Robo-advisers.

It took Mr Ow two years to find the right people. AutoWealth began investing money in 2016 with S$500,000 from a group of initial investors, with a vision of bringing good investing to the masses.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

Around the same time, Michele (pronounced "Mick-el-ay") Ferrario, then chief executive officer of e-commerce platform Zalora, found himself getting constantly riled by poor banking service. "I'm a premium customer in a couple of banks. The level of service I received, the quality of advice I received, was incredibly sub-standard. It wasn't advice. It was a sales pitch." He cast about for a local robo-adviser to help him invest. Not finding something suitable, he decided to make one instead, and StashAway was born.

In 2015, Keir Veskiväli and Artur Luhaäär began building their robo-adviser as a tool for friends and family in their native Estonia. One thing led to another, and they were soon in Singapore to launch their product, Smartly, drawn by South-east Asia's rapid economic growth.

Smartly has since signed up around 500 people - mostly Singaporeans between the ages of 25 and 35. "They are looking for a financial product they can understand and therefore trust, and is digital as well. The closer they are to 25, the more they hate interacting with a real human being," reveals Mr Luhaäär.

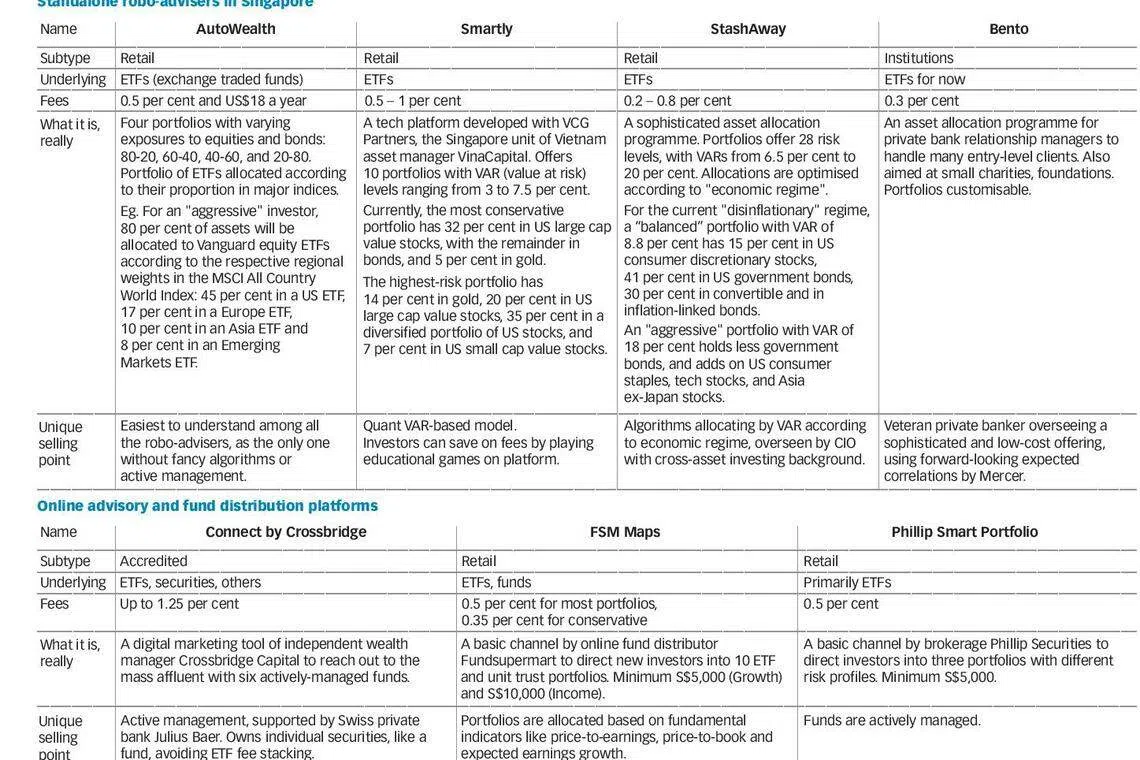

AutoWealth, StashAway and Smartly all claim to be robo-advisers, online services which use algorithms to pick investments for clients to meet their investment goals. Together with Bento, an offering for institutions and private bankers which launched in October last year, these four are the main standalone robo-advisers in the Singapore market today.

OCBC Bank is piloting a robo-advisory service with fintech firm WeInvest, which it launched in March. Meanwhile, digital distribution platforms for funds with varying degrees of active management are also springing up.

Connect by Crossbridge, a digital marketing channel for independent wealth manager Crossbridge Capital, and FSM Maps, an initiative by online fund distributor Fundsupermart, started up late last year.

Brokerage Phillip Securities also joined in the fray in March with its Smart Portfolio.

What's the hype about? How different are the Singapore robo-advisers from each other? Do they represent an existential threat to traditional advisory and wealth management?

Low fees with ETFs

Tim, a Brit in his 40s working in Singapore, tells The Business Times that expats like him get inundated with pitches for insurance-linked, supposedly tax-efficient wrap products, charging upfront fees of as much as 6 per cent.

Recently, something new has caught his eye: StashAway and Connect by Crossbridge advertising on Facebook. "I haven't decided how much to invest yet but the attractions are the fees, convenience and goals-based investing," he explains.

Low fees are critical to the robo-adviser proposition. Annual management fees can be fractions of a percentage point - cheap compared to an annual 1-2 per cent of capital charged by fund managers and another initial sales charge of up to 5 per cent going to bank or insurer distributors. The low minimum investment required by retail robos also makes them accessible to new investors. Smartly asks for a S$50 minimum, StashAway has no base sum needed, and AutoWealth requires just S$3,000 as a minimum.

What's captivating for many consumers is the "no-brainer" proposition that today's robo-advisers offer - exchange traded funds (ETFs).

ETFs, traded as if they were stocks, track the largest and most liquid securities in a sector or a market. They allow investors to easily hold positions in markets and sectors at extraordinarily low costs. The Vanguard S&P 500 ETF, for example, which charges investors a mere 0.04 per cent of assets a year, is up 95 per cent in the last five years, outperforming most active managers.

The asset allocation question

In a nutshell, a robo-adviser works like this. It first finds out your risk appetite like a traditional adviser would, albeit in a less-involved way. It then invests money accordingly in an ETF-based portfolio that claims to maximise returns for the risk you want to take on.

On one end, there are robo-advisers using simple rules of thumb to automatically allocate and rebalance assets. At the other end of the spectrum, human investment managers oversee complicated algorithms, like an actively-managed quant hedge fund.

The easiest model to understand is AutoWealth's - four portfolios with varying exposures to bonds and equities. If, after a stock market rally, stocks now amount to 2 per cent more in the portfolio, the extra two percentage points will be sold and invested in bonds. A second kind of rebalancing kicks in at the year-end to deal with shifts in the components of the underlying stock and bond indices tracked. AutoWealth stands out for its purity. "Other players still have active management here and there. We have clearly taken our side," Mr Ow says.

Smartly, meanwhile, applies modern investment theory in its model. Like US robo-adviser giant Betterment, Smartly uses what is known as the Black-Litterman model to calculate the expected returns of asset classes. Current market data is blended with fund manager views to pick out a portfolio with the highest expected return relative to a pre-set level of risk.

StashAway and Bento possess the most sophisticated algorithms, no surprise given their pedigree. StashAway co-founder Freddy Lim was global head of derivatives strategy at Nomura. Bento founder Chandrima Das was most recently head of managed investment sales and advisory at OCBC's private banking arm, Bank of Singapore.

Bento's model draws upon forward-looking asset class correlation data provided by consultant Mercer, rather than historical correlation. "Getting this rigour in the investment process for me was very important," says Ms Das.

She explains with an example: If only historical correlation were used, clients would be buying Japanese government bonds to diversify their portfolios, instead of emerging market (EM) bonds, which used to behave like equities. But given how the supply of EM bonds has increased, the market has become more resilient. So EM bonds would now be effective diversifiers, she adds.

StashAway pursues a global macro strategy. Asset allocation is determined by what economic regime the world is in, based on US industrial production and US headline inflation. US numbers are used because "every country is correlated to the US", says Mr Lim.

There are four regimes to optimise portfolios on: "recession", "disinflationary growth", "inflationary growth" or "stagflation", and a standby "all-weather" portfolio. Asset classes perform differently across different periods, and thus returns and volatility data cannot be mindlessly averaged together to optimise portfolios, Mr Lim argues. StashAway sets 28 risk levels.

The establishment is sceptical

Even with robo rebels pitching camp in the wings, the establishment seems smugly ensconced. They say the fancy algorithms, developed on back-tested data, remain untested in a crisis.

Tian Yafei, European banks analyst at Citi Research, points out that the biggest robo-advisers in the market are operated by ETF giant Vanguard and brokerage Charles Schwab. Incumbents like banks and asset management firms can use robo-advisory technology to better retain customers, build brands, and lower costs, she says.

Liew Nam Soon, EY Asean managing partner, says there is more hype than substance on whether a robo can perform complex investment advisory or react soundly to a big event like Brexit. "Until the technology and algorithms become more robust, nobody wants some sort of mis-selling," Mr Liew adds.

Lim Soon Chong, DBS Bank regional head of investment products and advisory, agrees: "While algorithms are helpful and computational technology have improved dramatically, the financial industry's ability to harness them to assess risk and make sound investment decisions have yet to be satisfactorily developed."

Charlie O'Flaherty, Crossbridge Capital head of digital strategy and distribution, worries that less-experienced robo-advisers might not "understand the gravity of what they're doing". "One big mistake could ruin the industry," he warns.

Even so, banks and asset managers are increasingly developing or acquiring their own digital platforms. Betterment, one of the biggest independent robos in the business with about US$10 billion assets under management (AUM), has joined hands with BlackRock and Goldman Sachs Asset Management to offer new portfolios, while Morgan Stanley will soon roll out its own robo-advisory service.

The question of viability could soon come up. In the US, assets managed by robo-adviser services are expected to hit US$166 billion this year, up 10-fold from 2014, according to the Aite Group, a Bloomberg report says. Aite Group estimates that the total will rise to more than US$435 billion by 2018.

While the low fees are a huge draw, the business model only works on volume. AutoWealth, Smartly and StashAway all use Saxo Capital Markets to execute their trades. Trading costs average around 0.1 per cent, Smartly's Mr Luhaäär notes. AutoWealth's Mr Ow says that the US$18 it charges a year per account might barely cover trading and custody costs. All three robo-advisers, currently based in co-working spaces in Singapore, say they need substantially higher AUM before their business is financially viable.

AutoWealth's Mr Ow estimates he needs S$60 million to S$100 million. Smartly's Mr Luhaäär is gunning for a couple hundred million. StashAway's Mr Ferrario is aiming for S$1 billion or more, equivalent to the requirement for a traditional retail fund management company to qualify for a licence here. "That's what we set out to do since day zero," he points out. "The company only lives, only if it becomes that. We never set out to build a small garage shop."

Some market consolidation will be in order. BT understands that more than 2,000 people are on robo-advisory platforms so far, putting in more than S$20 million. It is a promising start, but still very far away from breakeven numbers.

The regulators have taken a favourable view. In a consultation paper released in June, the Monetary Authority of Singapore said it "welcomes the offering of digital advisory services" as it "has the potential to improve consumers' access to low-cost investment advice".

It also hinted that it was prepared to exempt robo-advisers from certain requirements, given that much of the investing is passive and in relatively low-risk ETFs, although safeguards must be put in place.

Consumer education will be a challenge. As OCBC Bank head of e-business and business transformation Pranav Seth puts it: "Unit trusts, people still understand. ETFs, people don't understand. Portfolio-based investing, people don't understand. Rebalancing, even less people understand. Unless you break through all these barriers, you'll never have a massive uptake."

To which StashAway's Mr Ferrario counters: "You can drive a car without knowing how the engine works."

For now, a hybrid model seems the most likely to succeed. Even Betterment has added human advisers and also offers its automated advisory platform to financial advisers. AutoWealth has three people on the ground to meet clients with concerns. StashAway has a customer support team to answer questions on the same day.

Robos, evolved

Financial advisers in Singapore tell BT that digital advisory is a strong tool for them to interact with customers, and tech can be used to manage expenses given thin margins. As for performance, there's little data as yet on whether robos perform better than real advisers.

But humans will not be pushed aside so easily. Christopher Tan, CEO of boutique retirement planning firm Providend, says: "Robots cannot replace empathy. When markets are doing badly, and the emotions of investors get affected, a robot is not going to understand you."

Tim, the British expat, says: "I'd also use a reputable traditional adviser, so it would be a mix."

The robo-adviser space remains fertile ground for experimentation. The Holy Grail, according to a Deloitte report, involves self-learning artificial intelligence algorithms shifting allocations based on market conditions and individual needs.

Ned Phillips, founder and CEO of robo-adviser developer Bambu, believes that a robo should focus on achieving customers' goals, not beating the market. Bambu developed Connect by Crossbridge, as well as a digital advisory tool used by Standard Chartered Private Bank.

Future robo-advisers will be centred around savings and data collection, he says. And any company with the data at hand - from insurers to telcos, online retailers to ride-hailing companies - could jump in. Uber has partnered Betterment to offer retirement savings plans, he notes. Grab is driving cashless payments for taxis, and a peer-to-peer fund transfer function just kicked in.

"Anyone with an e-wallet can launch a robo," Mr Phillips adds.

Based on all kinds of readily available details like where people eat, shop or holiday, banks can work out what kinds of people are likely to reach which financial goals, and nudge them with appropriate products. To Mr Phillips, the robo-revolution will spread far and wide, powered by the young who "will tell you everything".

"Consumer brands don't want to sell products. They want to get into their consumers' whole financial journey," he says. And ultimately, that's what robos will be about - a tool for companies to anchor themselves into the "save-spend-invest life cycle".

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.