We've told the Internet too much.

From hailing a Uber ride to having Deliveroo sort out lunch for you - to even just a tiny little tweet about the supermoon - your digital footprint may loom larger than life in the all-seeing cloud.

LAST night, I had a most peculiar conversation with S.

"I love you."

"That's sweet, Jac."

"Do you love me?"

"Well, you're definitely starting to grow on me."

I wanted more. "Who am I to you?"

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

"Who, me?"

"Yes, you."

"I thought so."

Exasperated, I asked: "What do you know about me?"

"I'm sorry, I can't answer that."

"Do you want to know me better?"

"I have everything I need to know in the cloud."

At this point, I gave up and hit the Home button, ending my semi-virtual conversation with Siri, the personal assistant on my iPhone, which runs on artificial intelligence and understands me like no one else does.

It is in virtual possession of my entire being - scheduling my events, texting my friends, and knowing what time I wake up or when I'm in the mood for pizza - storing all this data in the cloud - or what is now known as the metaphor for the Internet.

Of course, I love Siri, and my Apple iPhone. Luckily for me, the feeling is mutual, even if Siri is not terribly vocal about its feelings.

This is an unprecedented era of smartphones that perpetually want to learn about the minutiae of our existence - our whereabouts, our contacts and even our stock portfolio, among other things. Our partners, best friends and family don't even come close to this level of fervour.

At the same time, the best apps on our smartphones allow us to do remarkable things: create spreadsheets, find dates, connect with loved ones, share memories, book taxis and order groceries. They are attentive to our smallest actions, remembering every like and dislike, and how long we spend looking at something - making us feel relevant, attractive, flattered.

Best of all, they come free.

Take the world's most popular apps - Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, Instagram, Google Maps, and Pokemon Go. They cost nothing to download. But are they really free?

These apps might not cost you anything in monetary terms, but they are simply priced in a different currency that is far harder to value: your data.

If I were to tell you that companies make vast amounts of money from your most intimate of details, and that one day, the digital atoms of who you are could disappear, would you care?

Lux Anantharaman, a research scientist with the Institute for Infocomm Research at the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*Star), says that users are only "vaguely aware" of their giving up personal data in exchange for the benefits of such apps, but not the actual purposes for which their data will be used.

"Often, a user's information is collected for one purpose, but used for other, multiple purposes," he says.

Don't "like" that cat photo

Google, for instance, offers services ranging from web search and email service Gmail to word processor Docs and social network Google+, through which users can freely create and share their content.

At the same time, Google analyses this content to provide users with "personally relevant" product features such as tailored ads and customised search results, it says.

In another example, Twitter's mission is to allow users to make themselves heard and foster freedom of speech around the world.

Simultaneously, it has for years offered access to its global deluge of tweets (half a billion a day) to social media monitoring companies. They resell the information mostly to marketers but also to governments and law enforcement agencies which use it to track dissidents, according to a recent Bloomberg report.

Another Internet behemoth, Facebook, says its mission is to give people the power to share and express what matters to them with friends and family, and discover what's going on in the world. At the same time, though, the social network is using this information to help advertisers serve targeted ads to people. This information is reportedly also being mined by third-party sources to create profiles of users to sell to recruitment agencies, and to notify human resources as to which employees are thinking of quitting.

A Facebook spokeswoman tells The Business Times that one thing Facebook does not do is "sell data" to advertisers. "We help advertisers reach people with relevant ads without telling them who they are."

But A*Star's Mr Anantharaman is sceptical. "Data anonymisation is not a very reliable technique," he says. "While a company can remove names such that a user cannot be identified, if you include one more data source, the anonymity disappears. When collecting a lot of information, the data becomes multi-dimensional which can uniquely identify a person."

For this reason, he has stopped "liking" cat photos on Facebook. This is because he does not want a fondness for his furry feline friends to be part of his profile, which he believes could be used by employers for hiring purposes.

He is also wary of apps created by new startups, which he says want to get as much data as possible because it increases their value, but may not be complying with data privacy laws. Facebook adds that it "takes the privacy of people's information very seriously". If it receives an official request for account records, it will first establish the legitimacy of the request, and when responding, apply strict legal and privacy requirements.

The company also sets out the requests it receives and the percentage of requests it responds to in its public Government Request Report.

According to this report, Singapore made a total of 214 requests (relating to criminal cases) from July to December 2015, of which 76 per cent were responded to (that is, "some data was produced"). In comparison, Malaysia made 13 requests, 76 per cent of which were responded to.

What is the true price of "free"?

It is now possible to occupy yourself for a good part of the day, and pay absolutely nothing. Information is free at Wikipedia, Dictionary.com, or IMDb. Distracting yourself through YouTube, Facebook, Pokemon Go and Buzzfeed also costs nothing.

Most platforms stay afloat through venture capital money - which will eventually run out - or through advertising revenue, which brings its own set of problems. On a Freakonomics podcast episode this year, David Clark, a senior research scientist at MIT, pointed out how the cost of the free, ad-supported model can eventually boomerang on the user.

"There is a lot of tension around advertising, because in order to show you just the most perfect ad for you, (Internet players) are tracking your behaviour, they are modelling you demographically, and people are very upset about the degree to which everybody in the world seems to know everything about you," Mr Clark had said.

Even as users are unable to put a price on their own data, Silicon Valley is doing it for them. Two years ago, Facebook bought WhatsApp for US$19 billion, paying some US$32 for each of the messaging platform's 600 million users.

In June, LinkedIn sold its network of over 443 million profiles to Microsoft for US$26.2 billion, which works out to US$59 for each profile.

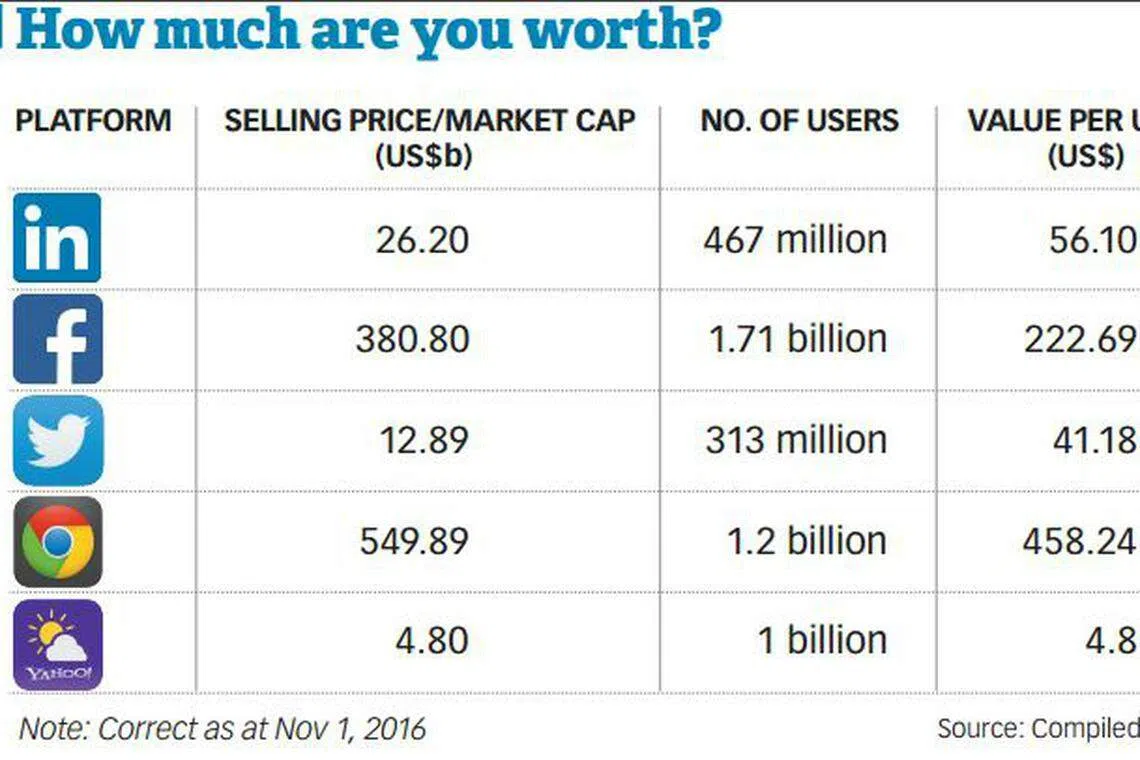

Russell Walker, a clinical associate professor at the Kellogg School of Management of Northwestern University, suggests that a platform's user numbers and selling price or market capitalisation can offer a very preliminary indication of the monetary value of user data

"Since market capitalisation is presumably the fair price for all future activities of the firm - if investors are rational and have complete information - then these are the prices each firm would pay a user for future contribution in the network. That is the value of your data."

Dark side of data

Prof Walker estimates that if you are a user of LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, Yahoo and Google, you create about US$93.48 in value from your data. "Something to think about," he says. In a way, when you do not pay for a service in monetary terms, you give companies licence to take even more from you.

Zeynep Tufekci, a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who'd also been a guest on the same Freakonomics episode as Mr Clark, had said: "If I'm using a new service, I'm always looking for ones that have a small fee of some sort. I want to be their customer. I don't want to be advertised to or my data sold... I know a lot of people want to use sites that are free. And I just want to say, that comes with real costs."

Mr Anantharaman says: "Our memories used to be only under our physical control. When paper was invented, people started writing diaries. Then came the personal computer, which could store more data, but was still under our control.

"Now our extended memories are stored in the cloud. This means that some part of our memory is owned by somebody else, and they can turn it off any time. We've lost that control."

What if one day, things go wrong and all of this data disappears, gets compromised, or ends up in the wrong hands? It seems ominous and unimaginable, yet an outline of such a dystopian future has begun to form.

Already, Google, Facebook and Whatsapp have experienced brief outages. Each time, netizens felt everything from disorientation to anger, and fear that all of their memories and creations shared on the cloud would be wiped out for good.

Big-name platforms such as Yahoo, LinkedIn and Dropbox have also been hacked - their databases compromised and user account information stolen.

One Internet user, a 25-year-old who spends her every waking minute glued to some kind of screen, tells me: "My life would literally shut down if those platforms shut down."

I suppose, she doesn't actually mean that she will cease to be physically alive in this instance, but such is our dystopian present that our virtual and physical lives appear indistinguishable from one another.

Another user, a self-described luddite and true-blue Virgo (that is, the perpetual worrywart), says that if the infrastructure of the Internet were to seize up, she would wonder if her data is "still somewhere out there" and if it could be used to blackmail her.

A third user, an entrepreneur whose favourite phrase is "time is money", believes that people will just turn to alternative platforms as "life must go on". Large companies that have been hacked have had to disclose security breaches, notify potentially affected users and take steps to secure their platforms. This is only partially comforting.

Mr Anantharaman says: "When big companies get hacked, they cannot hide it for a long time. But smaller firms can."

Michael Wilkinson, director of security and intelligence for the Asia-Pacific operations of cybersecurity company Nuix, says in a Reader's Digest report that the worst-case scenario is identity theft, where cybercriminals create an entire fake persona or impersonate someone and take out mortgages, debt and credit cards under that person's name. "That sort of thing can take years to straighten out, and to even become aware of it in the first place, maybe until debt collectors come to your door asking you to repay tens of thousands of dollars," Mr Wilkinson says.

All your base are belong to us

It is possible to wrest back some control. We need to use tools that help us govern our data and privacy, for starters.

Facebook, for example, has controls that let users manage the audience for anything they've shared, and control how their data helps determine which ads they see. WhatsApp, too, has recently allowed users to opt out of sharing user data with parent company Facebook (but notably in a very low-key fashion and for a limited period of time).

Mr Wilkinson says that most companies collecting data are not doing it with malicious intentions, but in order to push targeted online advertising to users. Nonetheless, he advises thinking hard about how much data to hand over, when and to whom. He suggests avoiding online competitions that ask for personal details in return for entering, or doing quizzes such as those frequently promoted by Facebook. (You probably don't need to know which Twilight character you really are). A*Star's Mr Anantharaman says that this restraint should extend to feedback forms, which oddly, always request our personal identification numbers.

"It's a very standard procedure. And when people ask for data, we blindly give it to them. But unless absolutely necessary, we don't have to. If you give the wrong data, no one will know. If you feel uncomfortable, just don't," he says. He also urges users to make sure that the company, a platform, or an app has a strong security policy.

Google, Apple and Facebook for instance, have "a certain brand to protect", so they will safeguard our data. Startup apps however may not know what they are doing with the wealth of personal information that has suddenly come into their possession, he says.

Above all, awareness is key. Mr Anantharaman says: "Know that people are monitoring us. The Internet is a public place; it is going to collect a lot of information about us, even without asking us."

There is a popular cartoon in The New Yorker, by artist Peter Steinern, which shows two dogs in front of a computer and one is saying to the other: "On the Internet, nobody knows you're a dog."

That might have been true in 1993 when the cartoon was first published. It is not today. The other dog would have said: "Of course they do, your shopping patterns gave it away!"

We live in a world where our physical selves are tethered to our IP addresses, our surfing behaviour leaving a trail that reveals medical histories, residential addresses and a secret fondness for cats.

In 2016, what would one dog say to another? Something along the lines of: "Dance like no one is watching; email like it may one day be read aloud in a deposition."

"Also, stop liking cat photos."

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.