Trump tariffs cast a cloud over Jaipur, India’s gemstone capital

Few believe the city will lose its crown as the gemstone capital of the world

[JAIPUR, India] Inside a bright, bustling room in a factory in the city of Jaipur, Rajasthan, Neeraj Lunawat held out a piece of rubellite, its deep red glinting faintly under the fluorescent lamp.

“Do you see the imperfections?” he asked.

To my untrained eye, the gemstone looked flawless.

But Lunawat, 58, pointed out a line in it – foreign substances like another mineral crystal, liquid or gas can often get trapped inside a gemstone as it forms.

He explained that jewellers like himself have to get the stone cut in such a way that the colour and shine of the stone would absorb the trapped substances.

For generations, Jaipur has been known for the unmatched expertise of jewellers and artisans who can transform unpolished rocks into dazzling emeralds, rubies and other coloured gems. But in recent months, the livelihoods of thousands who depend on the jewellery trade have come under threat.

In August, the US – India’s largest export market for gems and jewellery – imposed a 25 per cent tariff that was later doubled to 50 per cent as punishment for India importing oil from Russia.

The impact was immediate: Orders were halted, shipments were put on hold, and buyers were left wondering if they should start developing alternative markets.

The timing of these developments was particularly inopportune because almost half of all jewellery sales in the US occur during the Christmas quarter, a period that jewellers look forward to.

Ankur Daga, 47, who co-founded Angara, an online bespoke jewellery platform specialising in diamonds and coloured gemstones, noted that the jewellery trade would be unable to recover its losses in 2025 even if an India-US trade deal is in place by October or November.

The fourth quarter of the year accounts for 40 per cent of total jewellery sales in the US, with shipments taking a minimum of 10 days to reach the US from Jaipur.

“We are going to run into a situation of a tremendous shortage of goods; there is no way to fix the issue. People will suffer from cash flow problems,” said Daga.

He has stopped manufacturing for the US market from his Jaipur factory, which churns out 40,000 jewellery pieces a year and employs 75 people, with the slack being picked up by his other two locations.

Daga’s company also has factories in Bangkok and Los Angeles, and he is planning to launch his website in Singapore on Oct 6.

Referring to the heavy tariffs, Lunawat, whose company has around 800 workers and handles nearly 200 gemstones at any given time, said: “It’s like you are standing somewhere and lightning strikes.”

Cut above the rest

India is home to several jewellery hubs. For instance, Surat, in the state of Gujarat, dominates diamond cutting and polishing, while Mumbai thrives as a gemstone and diamond trading centre.

But Jaipur, the capital of Rajasthan, holds a special place.

Here is where the art of coloured gemstone cutting and jewellery-making has been nurtured for centuries. Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II, who founded Jaipur in 1727, had invited artisans, painters, weavers and jewellers to settle in his new capital.

When it comes to coloured gemstones, a human eye and touch are still essential.

Unlike diamonds, which are cut and graded using machines, coloured gemstones are more fragile. They chip easily, and the trapped substances, called inclusions, need to be cut in such a way that they enhance the shine of the gem. Jewellers point out that it is the inclusions that ensure each gemstone is unique.

As a result, the expertise of artisans and jewellers in Jaipur is not easily or immediately replaceable, said those in the trade. They call it “the eye” – the ability to recognise the quality of a gem and to figure out how to splice and cut it to maximise shine and minimise flaws.

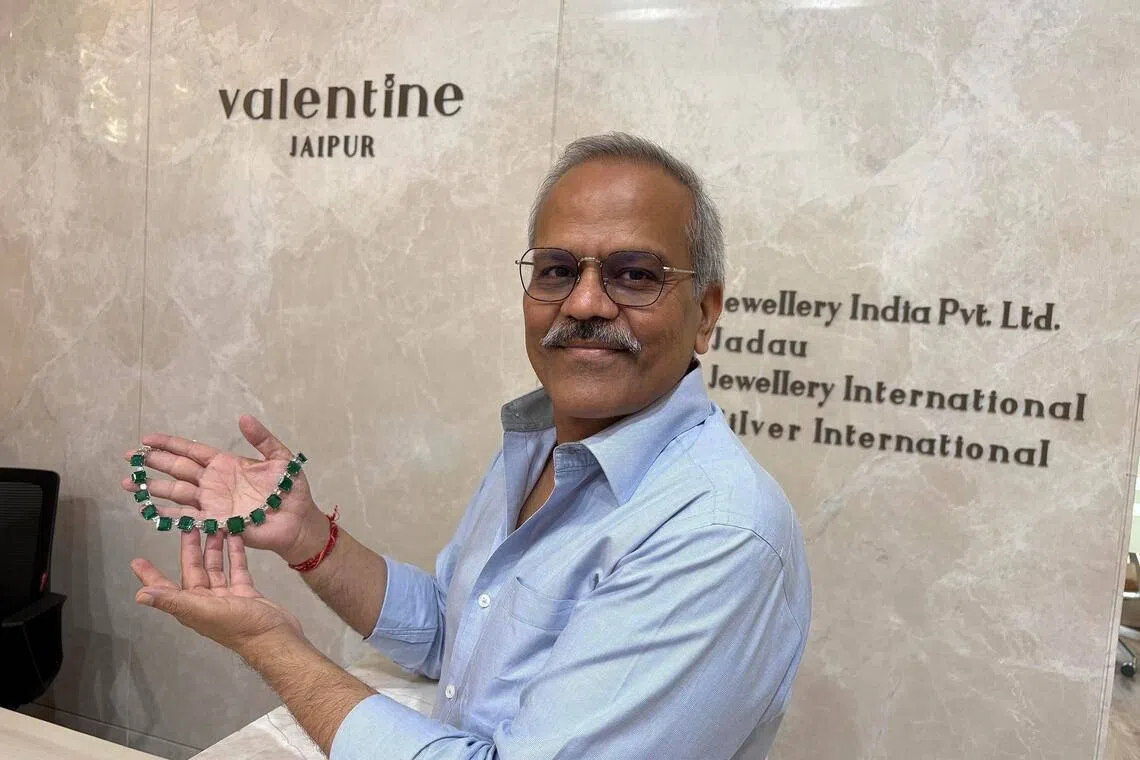

“A lot of the knowledge is here because natural gemstones are not totally machine-orientated,” Alok Sonkhiya, president of the Jewellers Association Jaipur, told The Straits Times (ST) at his office in Jaipur.

He held up an iridescent emerald necklace studded with diamonds.

“All of these stones were cut by hand. Machines can assist, but they can’t replace the skill of the artisan.”

Jewellers in Jaipur consider Thailand, which has been slapped with a 19 per cent tariff by the US, to be Jaipur’s only true competitor.

Long connection

Jaipur has a deep connection to the US built up over several decades when it comes to the gemstone trade.

The city exported jewellery and gemstones worth 178.9 billion rupees (S$2.6 billion) in the financial year from Apr 1, 2024, to Mar 31, 2025, with 17 per cent of that bound for the US.

Traditionally, many family-run jewellery houses in Jaipur have been sending a member of the family to live in the US to help source for gemstones from the mines in Latin America and facilitate exports to the US market.

Devendra Surana, now 72, went to New York in 1972 to support his family business in Jaipur.

“My uncle had already gone in 1966,” he recalled. “When he retired, I took over. The idea was to buy rough emeralds from Colombia and Brazil and ship them back to Jaipur.”

When he arrived in the US, there were very few jewellers from India. Now, there are around 100 offices in New York alone, he added, underlining how the connection has deepened over the decades.

But with tariffs making jewellery and gemstone imports from India unfeasible, inventories in the US are dwindling, and replenishment from Jaipur has slowed to a trickle.

“This is the biggest challenge we have faced,” said Surana, who has battled recessions, the 2008 financial crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic.

Similarly, Lunawat faces the challenge of keeping his business afloat; roughly 25 per cent of his company’s exports go to the US, with the rest headed to Europe and Asia. “I can’t replace the artisans I have. I won’t get these skills very easily in the market again,” he said.

Surge in popularity globally

Ironically, tariffs have struck just as coloured gemstones are enjoying a surge in global popularity.

A decade ago, they accounted for only 5 per cent of engagement ring sales in the US. Today, that figure has tripled to 15 per cent, said Daga, who is the chief executive of Angara.

“People feel a spiritual connection to gemstones,” he said. “The flaws make the gemstones beautiful. Natural gemstones come in hundreds of shades, and people are drawn to that,” said Daga.

Coloured gemstones are also cheaper than diamonds, with prices ranging from US$10 (S$12.90) per carat to hundreds of thousands of dollars per carat.

Celebrity endorsements have only added to the growing fascination with gemstones.

Princess Diana’s iconic blue sapphire engagement ring, with which Prince William proposed to his future wife, Princess Catherine, remains one of the most famous pieces of jewellery in the world.

In India, Nita Ambani, wife of tycoon Mukesh Ambani, Asia’s richest person, recently showcased multimillion-dollar emerald necklaces at high-profile events, sparking demand for knock-offs. Celebrities like Beyonce and Victoria Beckham have also flaunted ruby and emerald rings.

“More and more people are preferring individuality and self-expression and going away from a singular pursuit of excellence, which diamonds used to signify. There is a cultural shift. Also, gemstones as an asset are appreciating quickly,” said Daga.

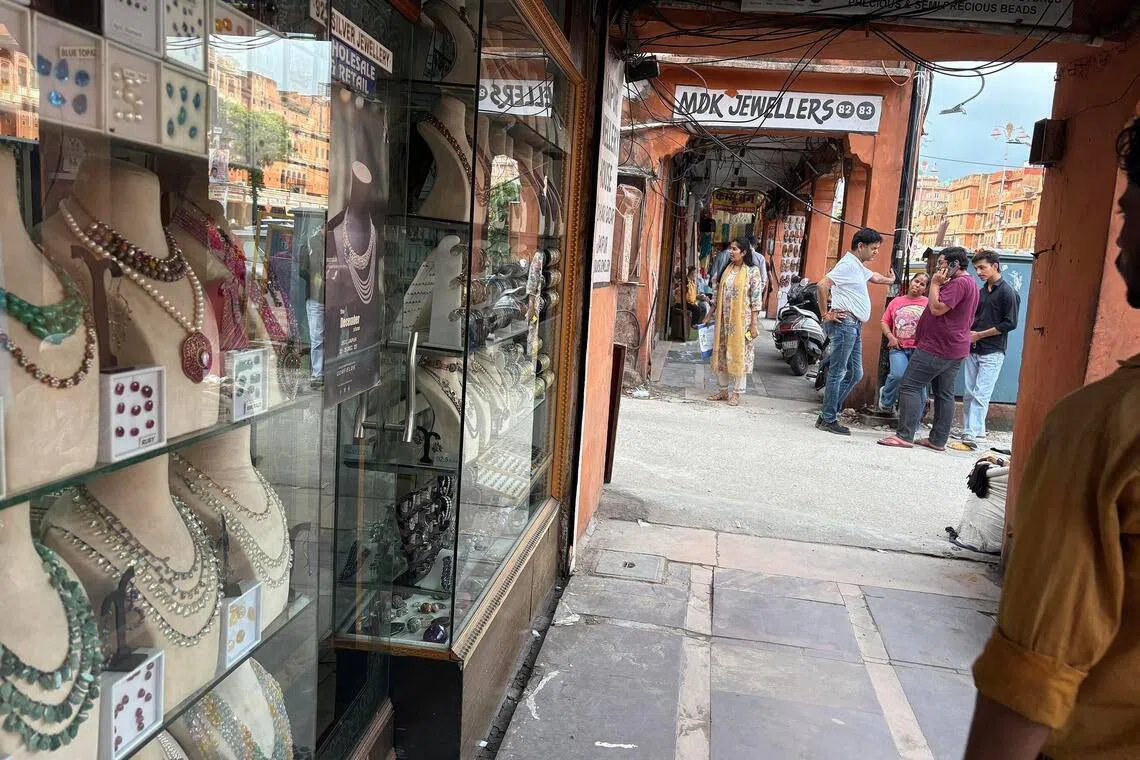

Despite the uncertainties sparked by the US tariffs, there were no signs of anxiety in the most historical part of Jaipur on a recent weekday in August when ST visited.

Johari in Hindi means jeweller, and at this bazaar, as old as Jaipur itself, shops painted in the city’s trademark pink offer necklaces, bangles and gemstones in every imaginable colour. These shops line the roads leading up to the 18th-century Hawa Mahal, a red-and-pink sandstone palace boasting 953 honeycomb-like windows.

Behind the shopfronts, cramped lanes lead to modest workshops where artisans hunch over stones worth millions, weighing, counting and cutting. In the narrow lanes, hand-drawn rickshaws loaded to the brim with goods jostle with bicycles, pedestrians and cars.

In one office, emeralds, worth millions of rupees, are scattered casually on a table as one man weighs stones on a scale and another counts them.

Few believe Jaipur will lose its crown as the gemstone capital of the world.

Industry players said training a new workforce elsewhere for the gems business will take time.

Daga said: “By the time another city is ready, the world will have changed again.”

Still, industry leaders see the crisis as a wake-up call.

Over-reliance on the US and other Western markets has left Jaipur’s jewellers vulnerable, and diversifying into Asia, Africa, Latin America and India itself is becoming more important now.

Said Sonkhiya of the Jewellers Association: “At least for a short period of time, it’ll be a bit tough. But it should serve as a clarion call to people, because we are normally in a comfort zone. Most of us would go to the US or Europe.”

For now, the future is clouded for Jaipur’s jewellers and artisans, with nobody knowing what US President Donald Trump will do next.

“He is a businessman, not a politician,” said Kailash Mittal, 60, general-secretary of the Johari Bazaar Market Association, sitting in his shop surrounded by necklaces. He added, a little perplexed: “He does one thing in the morning and another by night.” THE STRAITS TIMES

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.