Benefits of forcing banks to adopt taxonomies outweigh costs: former PBOC chief economist

It can become a very powerful incentive for poorer performers to improve

[SINGAPORE] Central banks should consider making it mandatory for financial institutions to adopt their respective national sustainable finance taxonomies, as the benefits would outweigh compliance costs, said Dr Ma Jun, former chief economist at the research bureau of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC).

When central banks mandate financial institutions to report their green lending with the criteria set out in their sustainable finance taxonomies, it allows for better data collection and comparability of these transactions among different banks.

“Taxonomies become useless when they are not used. You should recognise the benefits of forcing banks to use them... The benefits of usage on a mandatory reporting basis are much, much bigger than a very small cost of being compliant,” he added.

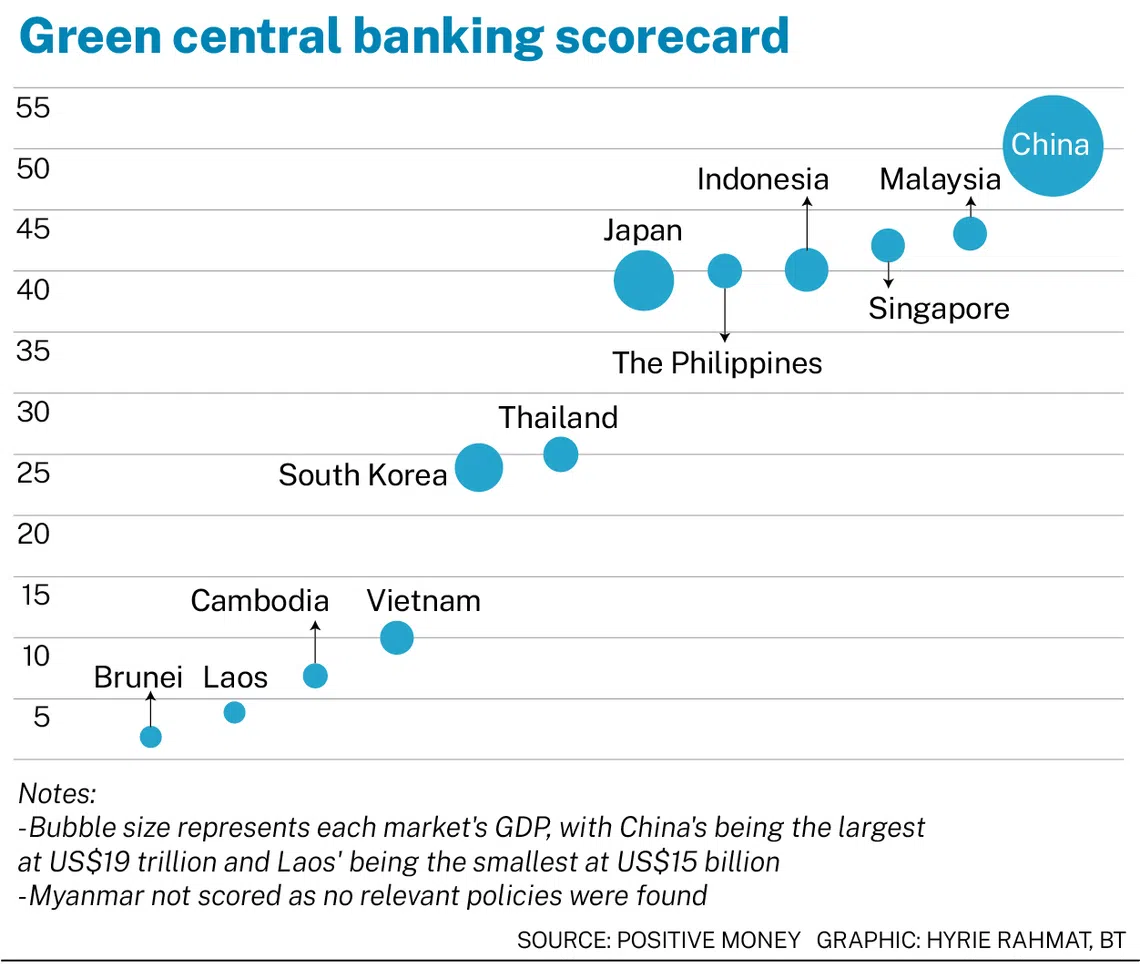

Dr Ma was speaking at a panel organised by Positive Money – a non-profit that advocates for central bank policies to align with climate objectives – which launched its first green central banking scorecard focusing on the Asean Plus Three markets. These refer to the 10 Asean countries, as well as China, Japan and South Korea.

While China had mandated its banks to adopt its green finance taxonomy since it was first launched in 2016, there are not many central banks in the rest of the world that have done so.

The Monetary Authority of Singapore, for example, had encouraged the financial sector to reference the Singapore-Asia Taxonomy as a complementary tool in their green and financing objectives. It had also assessed the extent by which the taxonomy has been adopted by the three local banks, but has not made it a requirement.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

Sustainable finance taxonomies set criteria and thresholds for a range of economic activities that would be considered eligible for sustainable and transition financing.

With the mandatory adoption, banks in China also had to report to the PBOC the amount of green loans issued, the level of growth, as well as the green loan ratio out of their total outstanding loans.

Dr Ma said that these collated numbers can help to compare green performance. For example, if one bank shows a very high green loan ratio, and another shows a very low figure, the contrast can become a very powerful incentive for the poorer performer to improve. So making it mandatory for financial institutions to adopt their national sustainable finance taxonomies can help to strengthen the green initiative within the banking system.

SEE ALSO

However, Laura Canas da Costa, global policy co-lead at the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative, said that voluntary frameworks have also been instrumental first-movers in allowing financial institutions to innovate and experiment.

Many advances in the sustainable finance landscape, such as corporate disclosures, climate risk pilots, started out as voluntary frameworks in many markets, she added.

“It’s not an either-or (choice). Mandatory or more regulator-led initiatives are really key for levelling the playing field and to create the kind of transparency and consistency... I think we need an element of both to drive this market and this whole trend forward,” said da Costa, who was also speaking at the panel moderated by The Business Times.

Green central banking scorecard

The mandatory approach has helped China score the best among Asean Plus Three countries in Positive Money’s inaugural green central banking scorecard focusing on this region.

China’s strength among these 13 central banks comes from its spread of monetary and financial policies assessed to have medium impact.

For example, there are requirements on banks and insurers to further integrate environmental considerations into their policies, and the central bank carries out climate stress testing of Chinese banks.

However, the report recognises that countries with higher gross domestic product, as well as GDP per capita should generally be expected to be further along in the development of green central banking policies, as they are better resourced and often have greater institutional capacity to develop and implement such policies.

Countries that have contributed a greater proportion of total historical carbon emissions also have a greater responsibility to be leading the implementation of robust green central banking policies.

For these reasons, there should be high expectations on China in terms of leading on the development of green central banking among Asean Plus Three.

“Given the level of political and economic influence China has, its progress in green central banking is not just of domestic importance, but has the capacity to shape and expedite decarbonisation and economic transformation away from ecologically damaging activities throughout the region,” read the report.

Across the region, however, none of the Asean Plus Three countries has implemented policies that meet Positive Money’s criteria for “high impact” actions, which is defined as measures that actively shift finance away from the most ecologically destructive sectors, notably fossil fuels.

This, however, is unsurprising given the region’s heavy reliance on fossil fuels to power its growing economy.

While Indonesia was considered to be a strong performer in the scoring, the report noted that one critical flaw with the country’s taxonomy is its classification of some coal-fired power plants as transitional, which undermines its wider integrity.

Also speaking at the panel, Dr Heru Rahadyan, deputy director at Bank Indonesia’s department of inclusive and green economy and finance, said that the central bank needs to integrate climate carefully given the country’s dependence on carbon-intensive sectors.

“A transition that is too fast risks instability, but too slow would risk climate vulnerability,” he said.

While he agrees that there is an absolute need to phase out the use of fossil fuels, it is not a central bank’s duty to make a decision on whether to turn off the tap, but the government’s.

What Bank Indonesia has done is set financing and capital requirements on green lending, and to gradually tighten the criteria.

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.