Climate tech beckons

The global race to net zero presents an abundance of opportunity for investors in areas such as technology and green infrastructure

ROUNDTABLE PANELLISTS:

- Xiaying Zhang, director, private investments, Apac client group, Wellington Management

- Rachel Teo, managing director, head of sustainability and head of total portfolio sustainable investing, GIC

- Mathieu Forcioli, global and Asia-Pacific head of alternatives, investments and wealth solutions, HSBC

Moderator: Genevieve Cua, wealth editor, The Business Times

THE race towards a net-zero world is unrelenting, but there remain many challenges – not just in terms of funding, but also in the development of solutions to speed up the transition at scale. Technology is a powerful enabler.

We speak to the experts about the opportunities in climate-related tech.

Q: What is the opportunity set in climate tech for investors, and what types of innovation are most promising?

Xiaying Zhang: We believe the market opportunity for mitigation- and adaptation-related climate solutions is enormous and necessary. While some individuals and companies may be willing to make trade-offs for more climate-friendly solutions, it is unlikely that society will accept trade-offs at the scale needed. People are unlikely to stop travelling and consuming, and businesses are unlikely to stop producing.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

Regulation will be essential, but ultimately, solutions will need to be market-driven and stand on their own to be truly scalable.

The range of investable climate solutions continues to broaden and expand. We continue to see declining costs and increased market adoption in areas such as renewables and electric vehicles (EVs), and this is likely to ramp up over time with ongoing scientific and technological innovation – for example, advances in solar materials and battery technology.

Regarding adaptation, improved near-term weather and longer-term climate forecasting should help companies adjust their operations in real time to account for extreme weather events and to incorporate future climate risks into long-term asset planning. Parametric weather insurance is emerging as a way for businesses and consumers to hedge their revenue or asset risk around weather-related risks.

Together, these combine into a wide range of potentially high-return, high-impact opportunities, particularly within growth-stage climate-tech companies.

We also think several secular trends support disruptive climate-focused entrepreneurs. For example, as the list of countries and corporations committed to net-zero emissions grows, we expect high levels of global infrastructure spend, creating a foundation for innovative, asset-light companies to build on. In addition, consumers are demanding transparency and choices that match their climate-related values, and companies are in search of innovation that can help them meet that demand.

In our view, this creates an enormous opportunity for innovations and technology that address climate change while delivering a superior user experience without trade-offs. We see all of this reflected in the growth of climate-related investments across public and private markets.

Rachel Teo: Based on the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) Net Zero by 2050 report – which sets out a pathway for the global energy sector to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 – the investable opportunity until 2050 in the scenario where net zero is indeed achieved by mid-century is approximately US$126 trillion, or US$4.2 trillion a year over the next 30 years.

However, even in a Stated Policies Scenario, as the IEA calls it, there is still significant momentum behind green solutions because of favourable conditions – such as existing and committed climate actions by governments, and the fall in climate change-related technology costs.

The opportunity set for investors when it comes to technology solutions that aid the transition lies both within transition assets and green solutions providers. The former focuses on supporting high-carbon businesses that are credibly transitioning towards low-carbon business models, while the latter is about funding companies that are providing decarbonisation solutions for transitioning businesses and the economy at large.

In both categories, the opportunity set for investors is broad – spanning public and private markets and across the full capital structure.

Among six sectors that climate technologies can be categorised into (such as electricity, transport, buildings, industrial processes, low-emission fuels, and agriculture, forestry and other land use), electricity and transport represent the largest investment opportunities.

Some technological solutions are already well established, such as solar and wind. But many are still nascent or early-stage, such as direct air capture (DAC), green hydrogen and nuclear fusion.

While we do see many promising innovations, GIC’s investment decisions are based on value creation and returns, including factors such as attractive risk-reward proposition and a good path to commercialisation.

At GIC, we invest across both the entire technology spectrum and various stages of a company’s growth because of our long-term orientation, flexible capital, and multi-asset portfolio. Our investments range from private equity (in technologies such as carbon capture or green steel) to infrastructure (in a company building EV charging infrastructure) to public equity (in an environmental, social and governance or ESG data provider), to debt financing (for companies working on geothermal energy solutions). This breadth allows us not only to invest in multiple innovative solutions, but also to support firms at various stages of development.

Mathieu Forcioli: As a bank, we have a leading role to play in mobilising the transition to net zero by supporting our customers in their own transition to lower emissions. This involves helping companies access sustainable finance and expertise, and investing in climate solutions in collaboration with our partners and investors all over the world to scale up new technologies and approaches at pace.

The global race to net zero presents an opportunity for investors, such as opening up new asset classes and products targeting, for example, technology and green infrastructure. At this stage, however, it is estimated that around half the technologies needed to meet the challenge are not yet commercially deployable and require rapid scaling-up.

To date, the major focus in terms of decarbonisation has been low-carbon power generation, but we know this will not be enough to meet targets. Reducing emissions in the transport sector is another focal point, helping to drive substantial disruption in the auto and mobility industries from new competitors and technologies.

Therefore, one pertinent theme for investors today is “future transport”. The IEA estimates that 6 per cent of cumulative emission reductions in 2021-2050 could be achieved by using hydrogen-based fuels. Globally, government policy is driving both infrastructure development and vehicle transition via fuel standards, emission targets and incentives. Major vehicle manufacturers are accelerating their push to launch zero-carbon electric truck models, based both on battery and hydrogen fuel cell drivetrain technologies.

And, more broadly, the convergence of mobility and technology underscores the structural importance of semiconductors and software. This is an exciting opportunity for investors.

Cutting-edge, smart technologies and tech-based solutions can also help preserve nature, thereby indirectly contributing to net-zero emissions. We see many compelling examples of this, such as the deployment of artificial intelligence (AI) technology to convert food waste into insect-based animal feed, thereby helping reduce waste, carbon emissions and deforestation, and the use of agricultural methane detection technology to help cut emissions, reverse forest loss and regenerate biodiversity.

In addition, the application of financial technology to the climate change challenge is bringing new investment solutions and opportunities to the VC space, which are all important in the transition towards net-zero emissions.

Q: Venture capital is an avenue for investors to get exposure to climate tech. What are some of the challenges investors face when investing in climate tech?

Zhang: The climate crisis represents a useful example whereby many venture-stage companies are developing new technologies, which may play a key role in helping every sector of the economy transform by reducing energy consumption, increasing energy efficiency, and making global energy supply more sustainable.

At the same time, investors should not overlook that investing in these more illiquid private companies comes with specific risks. Therefore, this is only appropriate for investors who can take a long-term approach, as exiting an investment in the event of financial or sustained underperformance may be difficult. Moreover, transparency and governance may be more limited compared to investments in publicly listed companies.

Overall, some of these management teams may have less experience with public shareholder scrutiny and engagement than existing public companies.

Investors need to ensure that the investee companies ultimately deliver real-world solutions in the fight against climate change – meaning the rigorous measurement of actual impact is critical when identifying and monitoring investments.

However, impact measurement in private markets – particularly in VC – has specific considerations, including data availability and uncertainty, given that many of these companies are innovators and disrupters aiming to transform the industry. Further, if the investment thesis involves an innovative company with a new, first-to-market solution that is expected to be widely adopted, it is important to consider both the individual company and the potential ecosystem change.

Teo: Given the early-stage nature of venture investing, there are many challenges for investors, particularly in evaluating the technology and the commercialisation risk.

For some climate technologies, the solutions are still pre-commercialisation or scale-up. These require significant upfront capital and potentially years of research before any revenue is generated.

In some cases, there may be significant asset management requirements to help company management teams develop business strategy, support growth, and monitor performance. For investors, the bar for domain expertise to be able to evaluate opportunities is thus very high.

Additionally, business models may not be proven yet, and investors face significant uncertainties regarding the supporting ecosystem or infrastructure, including policies and regulations. The upshot, however, is that a climate tech startup which successfully achieves commercialisation is likely to have deeper competitive moats, making it tougher for competitors to replicate its products.

Climate technology presents unique organisational challenges for investors. As climate technology covers a wide range of sectors and markets, investment teams require broad-based sector and regional experience.

Furthermore, a long-term mindset is required to understand the full value of climate-tech solutions, as well as patience to support companies in their scaling-up.

The climate-tech ecosystem is a quickly evolving one, with new companies having the potential to disrupt incumbents. Engaging early in this space in a considered and controlled manner allows GIC to understand the evolution of these promising technologies and better discern the winners.

All investments, however, still carry risks. We look at these very carefully, put them through our stringent investment due diligence process, and subject them to risk controls which include starting with small investments and scaling up only when investments are sufficiently de-risked.

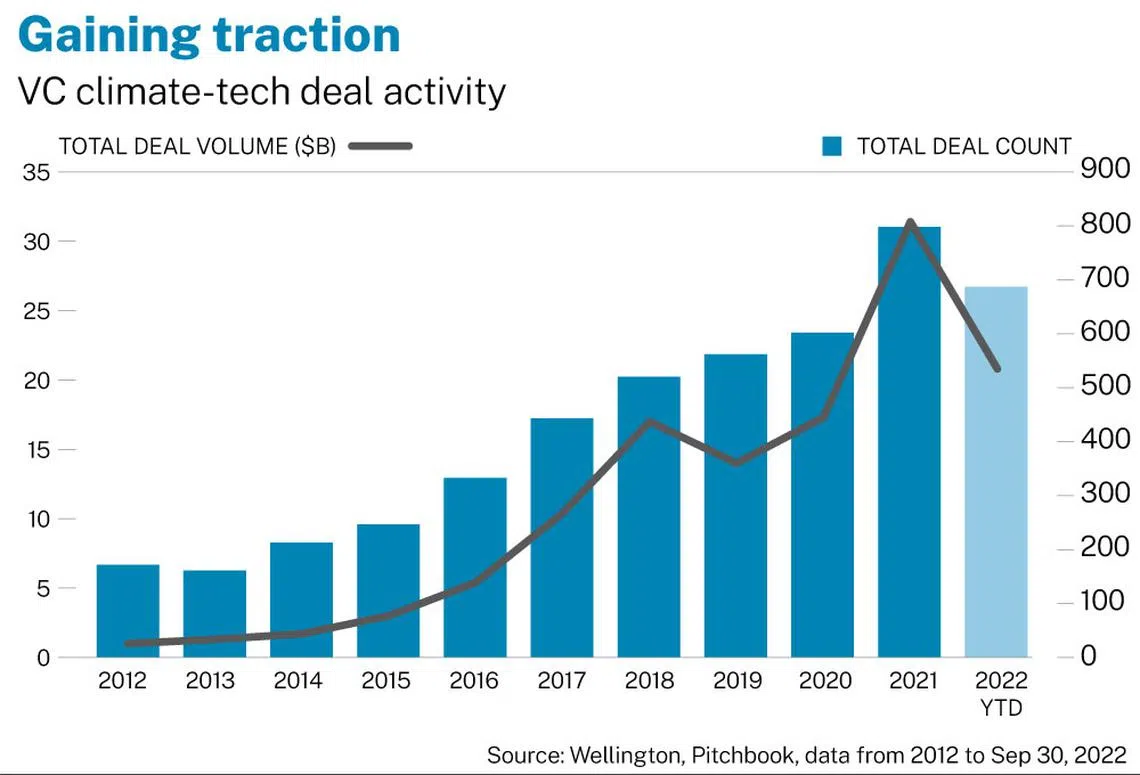

Forcioli: By some estimates, over a quarter of all VC funding goes into climate technology, with strong growth over the last decade. Still, the amounts we are speaking about represent a fraction of total flows into private equity and VC, and fluctuate each year, which may impact the sustainability and growth of the climate-tech ecosystem. Thus, challenges remain along the road to fulfilling the climate objective.

For example, while the long-term nature of private market investments lends itself to investing in technology, the illiquid nature of the investment and the uncertainty of cash flow generation later in life may suit a smaller pool of investors from a risk-return perspective.

Factor in the time and risk involved in research and development – and, in many cases, a fund’s lack of track record – and it is reasonable to see how this combination of longer time frames and unproven technology does not work for many VC investors, who typically want to see returns in five to seven years.

On top of this, investors can find it challenging to monitor impact outcomes or assess the alignment of sustainability objectives to a portfolio company or fund manager due to a lack of benchmarks and data, which makes reporting and disclosure more difficult.

But with challenges come opportunities. We see promising structural growth opportunities in clean energy and green technologies, including in innovations in solar, wind and hydrogen power, EVs, and green infrastructure such as flood walls which increase resilience of urban areas to natural disasters. Nature-based solutions in “climate smart” city planning can benefit city dwellers, reduce the carbon footprint and promote biological diversity.

Q: In climate tech, how should impact be measured and tracked; and how do you set investor expectations for the likely outcomes?

Zhang: We believe there are a few best practices that may help companies and investors navigate the unique challenges of measuring impact in this constantly evolving space. In setting investor expectations, there are four ways to authentically measure the progress companies create:

- Use existing wisdom to inform your approach. Generally accepted frameworks and principles in the industry include Impact Management Norms and Global Impact Investing Network’s Iris+ system. Each provides a holistic view of impact and how best to derive key performance indicators (KPIs).

- Commit to assessing real-world impact with KPIs. Gathering regular data over the life of an investment speaks to actual outcomes.

- Ensure business model alignment. Considering that companies may have several different growth options, impact investing is potentially most powerful when there is strong alignment between the profit-seeking objectives and the ability to solve a pressing social or environmental problem.

- Do more than report the data. Data should be analysed and benchmarked over time to embed feedback. This helps to inform ongoing discussions with the company, as well as influence future investments in similar sectors.

Teo: At a baseline level, tracking the financial performance and subjecting the company to the same standard of financial discipline as non-climate-tech companies are important and a key focus at GIC.

Impact measurement is an evolving space and best practices are still developing. Some possible measures could include activity-based metrics, such as the amount of fossil fuel-powered energy usage the technology replaces (or has the potential to replace), or the amount of clean energy generated.

We could also look to emissions-based metrics, including avoided emissions, which is something that GIC is evaluating. For solutions such as DAC, the relevant metric could be how much carbon dioxide is removed from the atmosphere.

Metrics could also be revenue-based, such as measuring the percentage of green revenues generated by the company based on globally accepted taxonomies.

Forcioli: Investors are looking for a greater level of transparency in portfolio companies and a higher utility level from deployed capital. The measurement and tracking of impact largely depends on the level of disclosure from portfolio companies and the availability of data. In general, impact measurement can be conducted via quantitative assessment and mission-alignment measurement.

For a quantitative assessment, a manager may employ a proprietary impact assessment tool to identify and assess ESG objectives, which are tracked using indicators such the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals or other climate-related science-based targets. For example, corporates may report active emission-reduction targets by years or Scope 1, 2 and 3 greenhouse gas emissions.

Alternatively, an investment manager may select bespoke KPIs for each investment to align mission and measurement. However, this approach may limit the ability to make comparisons across different investments, as the metrics can differ.

With the rapid development of climate tech, investment managers have also evolved their own measurement methodologies with the help of sustainability consultancies and agencies, but industry standardisation remains a work in progress.

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.