From LED lights to reverse osmosis, Ghim Li stays ahead of the sustainability curve

The home-grown clothing maker has taken steps to decarbonise its manufacturing process, but its next hurdle is getting businesses and consumers to pick greener options

THE fashion industry has a bad reputation when it comes to sustainability. This is arguably deserved: It accounts for 10 per cent of annual global greenhouse gas emissions – more than international flights and shipping combined, according to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

Part of the problem is that fashion houses need to sell a constant stream of clothing to stay profitable. But the other issue is cost: Sustainability can be expensive.

Singapore clothing manufacturer Ghim Li Group, however, is not allowing higher prices to deter its green ambitions. The company makes about 65 million pieces of apparel a year, and chief executive officer (CEO) Felicia Gan wants those pieces to be produced more sustainably.

Retailers and brands have shifted towards offering more sustainable and ethical clothing options, on the back of rising demand from environmentally conscious customers.

But that comes at an added cost for suppliers and manufacturers such as Ghim Li, which have had to pour money into cutting emissions at their factories and improving their abilities to produce sustainable products.

Gan sees this as a logical investment: “If you’re going in with the mindset of: ‘I’ll have to upcharge (for sustainable options)’, then you won’t have a healthy partnership … and you can never grow your business.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

“If you don’t start now, how are you able to react in the future when everybody is running faster than ever?”

Starting small

Ghim Li got its start in 1977, when Gan’s mother, Estina Ang, founded the company with just S$3,000 and six sewing machines.

Today, the company hires 9,000 workers across six countries. It has factories in Malaysia, Cambodia and Indonesia that are capable of knitting, dyeing and finishing apparel in-house.

It mainly serves the North American market, and supplies clothing to household names such as Walmart and Macy’s.

Gan, who took over as CEO in 2021, describes Ghim Li as a one-stop shop for retailers. The company not only manufactures apparel, but also provides market intelligence and design services.

By controlling the entire production chain – save for spinning its own yarn – Ghim Li is able to split orders into multiple batches and replenish stock based on how well they sell.

That helps retailers cut down on overstocking, which often ends up as waste, Gan said.

“For example, if you want to buy 10,000 pieces, I will make 5,000 pieces and store the other 5,000 in uncoloured form,” Gan said. “You then tell me which print or colour is selling well and I will react.”

Ghim Li’s control over its production chain was also what prompted the Singapore government to approach it to create the millions of reusable antibacterial masks that were distributed to residents. The company converted 20 per cent of its production lines for this.

Sustainability initiatives

The year 2016 was pivotal in the company’s journey towards sustainability. A major retail client started a project engaging its suppliers to reduce carbon emissions by a set amount.

Gan started small by switching to light-emitting diode (LED) lights, which use less energy.

The company also started installing transparent roofing at some premises, to let natural light in and to reduce its reliance on electricity. The two projects have reduced Ghim Li’s energy use by 30 per cent.

“People think that being sustainable is a cost driver,” said Gan, adding that many businesses get turned off by the large expenditures they need to fork out in the beginning.

“But we started with the low-hanging fruits. And when you start measuring the returns, it’s very encouraging for the team – and it gets you addicted to doing more and more.”

The fashion industry has taken flak for is its heavy reliance on water throughout the garment production process.

Making a pair of jeans takes 3,781 litres of water, which equates to around 33.4 kilograms of carbon emissions, UNEP figures show. Furthermore, fabric dyeing and treatment contribute to around 20 per cent of wastewater worldwide.

Ghim Li installed systems to condense the steam from its boilers into water that can be reused. That helped the company to save 50 per cent, or 1.1 million tonnes, of water that would otherwise have evaporated.

It also installed a reverse osmosis plant at its fabric mill to recycle 30 per cent of its wastewater discharge.

It has removed harmful chemical substances from its manufacturing process, and stopped buying any products that are on a restricted substance list provided by industry certification group Zero Discharge of Hazardous Chemicals Foundation.

Getting its entire supply chain free of toxic chemicals was particularly difficult, said Gan. Ghim Li’s mills provide around 65 per cent of its fabric needs. But the company buys the remaining fabric from other suppliers, which can be sensitive to cost.

“Toxic chemicals are very, very cheap. The cheaper it is, the more toxic it gets,” she added.

Ghim Li’s efforts have earned it some unexpected financial perks, as the global financial industry begins to pay attention to the sustainability profile of loans. When Ghim Li attained a set goal for emission reductions, one bank offered it a lower interest rate on its loan.

The company has also been using UOB’s sustainability compass. This is a tool that provides companies with step-by-step guidance on the different phases of going green. It includes information on regulations, standards and certifications, as well as recommended sustainable financing solutions.

Polyester problems

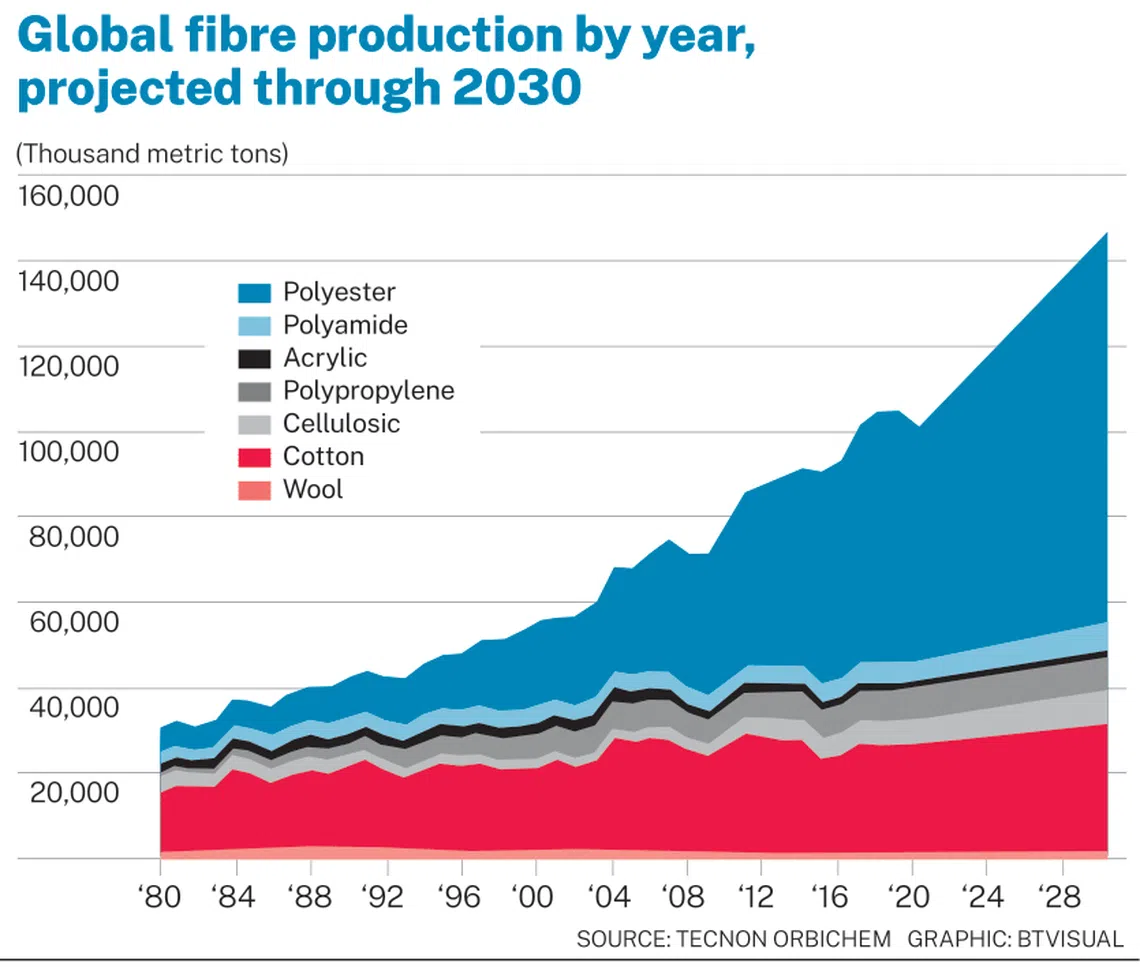

The fashion industry today relies heavily on petrochemicals in its use of cheap synthetic fibres.

The major culprit is polyester, a form of plastic derived predominantly from petroleum. It is the most commonly used fabric in clothing, with global production overtaking cotton in the early 2000s.

In 2021, Ghim Li had to deal with a doubling in cotton prices after the United States banned cotton imports from China’s Xinjiang region – making it even more difficult for retailers to justify using cotton over polyester.

Some of the clothing Ghim Li produces make use of recycled polyester from Repreve, a brand that makes these fibres out of plastic bottles.

But a majority of garments in the market are made with blends of different fibres. This allows the clothes to have different textures but makes recycling textile waste difficult, said Gan.

A major hurdle for the industry now is educating the public to support environmentally friendly fabric options instead, she added.

That includes getting businesses to shift away from blended fabrics and consumers to buy more sustainable forms of clothing.

“We have to educate them well so that they know what they are paying more for,” said Gan.

For its part, Ghim Li frequently encourages its clients to pick more sustainable fabrics by sharing its latest innovations.

In Singapore, Gan has also been working with government bodies and trade associations, such as the Singapore Fashion Council, to encourage more small and medium-sized enterprises to embrace sustainability.

One project she has been working on is to standardise the way the fashion industry in Singapore collects emissions data to prevent “greenwashing” – the process of making consumers believe their products are more eco-friendly than they truly are.

Ghim Li has also been working on developing botanical dyes made out of plants such as Indian gooseberries that are naturally biodegradable. The company will also be installing solar panels at its facilities.

“That way, we stay ahead of the curve,” Gan said.

She is cognisant of the impact the fashion industry has had on the environment.

“Our generation was spoilt for choice with fast, throwaway fashion that became cheaper and cheaper over the years,” she said.

But consumers are waking up to the perils of over-consumption, Gan added.

“We’re the last generation that can make a change to the environment. For your children and their children, you want to make sure that they’re not living in a rubbish environment.

“That is something we all have to think about.”

This is the second of a 5-part Green Business series, in collaboration with UOB, exploring sustainability trends across businesses and industries.

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.