Is the Progressive Wage Model making enough progress?

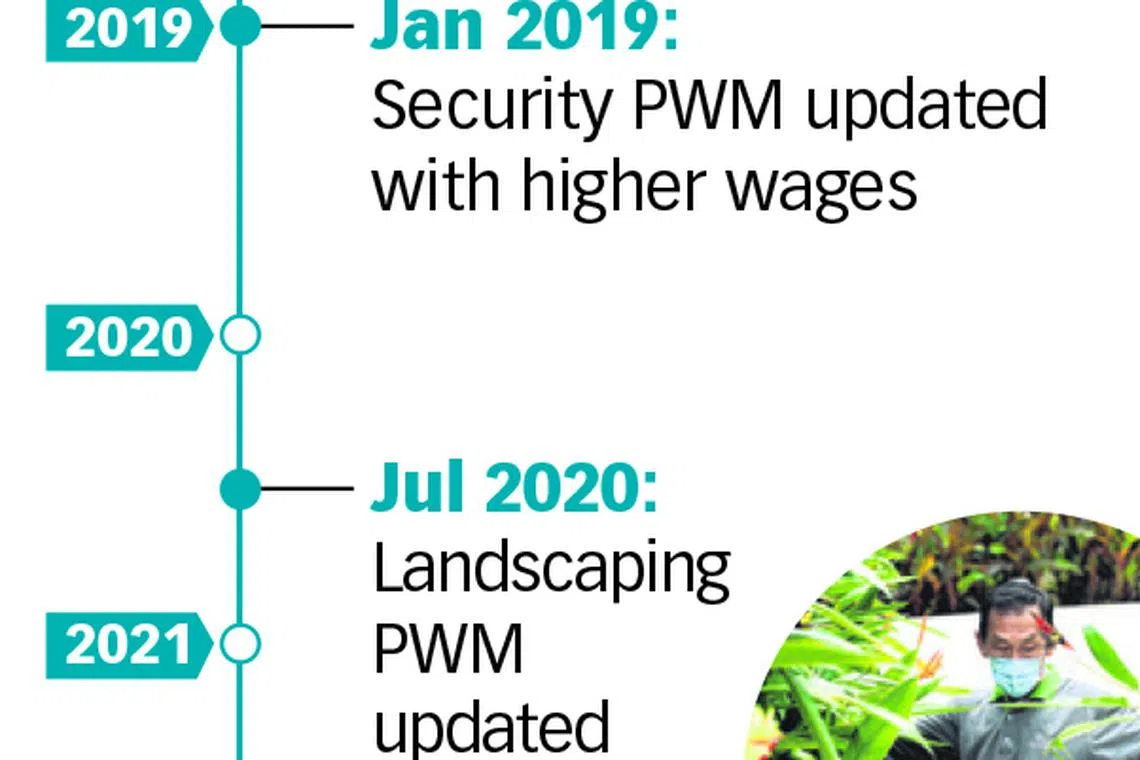

NEARLY a decade after the idea of the Progressive Wage Model (PWM) was introduced in 2012, this sectoral approach to lifting wages in Singapore covers just 85,000 workers. The government's eventual goal is for it to cover all sectors. But the question is how and when this can be achieved, and whether more needs to be done. In his National Day Message, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong spoke on providing "more sustained support" for lower-wage workers. A tripartite workgroup has been developing proposals that build upon Workfare - which tops up incomes - and the PWM, which sets out wage ladders and training and career pathways. For now, the PWM is mandatory in three sectors: cleaning, landscape, and security. As then National Trades Union Congress deputy secretary-general Koh Poh Koon noted in September last year, current PWMs cover only about 15 per cent of workers in the lowest fifth of income earners. PWMs are in the works for other sectors (see timeline below), including food services and retail, where up to 80,000 local workers could gain. Existing PWMs, which apply to outsourced workers, will also be extended to in-house workers, helping up to 50,000.

But this practical question is non- trivial. Current PWMs are enforced through licensing requirements; it is less clear how they might be enforced in industries without such regimes.

If PWMs will be rolled out to all sectors, one might wonder if this implies economy-wide legislation - and how that differs from a minimum wage.

Indeed, one idea is complementing the PWM with a minimum wage, as National University of Singapore senior lecturer Ong Ee Cheng and undergraduate Jennifer Yao Chenyin suggested in The Straits Times in May. "I think the main challenge is that the PWM is complex and takes a long time to execute," Dr Ong told The Business Times. It takes a few years from announcing a PWM to eventually implementing it: "From the perspective of workers, this lengthy period is extremely costly. That is months and years of wages that they could have been earning."

In theory, due to competition for workers, PWMs should have had a spillover effect in pushing wages up for other low-wage jobs, said Singapore University of Social Sciences associate professor Walter Theseira. "I suspect the spillover effect has not been that noticeable, because if it were, then there would be no need to expand the PWM," he said. A minimum wage floor would accomplish "what the PWM spillover was meant to, but did not achieve fast enough". In July, Monetary Authority of Singapore managing director Ravi Menon raised the idea in an Institute of Policy Studies lecture in his personal capacity, saying: "A minimum wage also signifies a societal value: That no one should be paid less than this amount for his or her labour." In its Labour Day message this year, the Workers' Party also continued to call for a minimum take-home wage of S$1,300, adding that it does not object to the PWM approach.

The idea of a complementary minimum wage found some support from the business community in The Business Times' Views from the Top column last week. But it is distinct from the PWM philosophy that higher wages must be tied to productivity. Dr Ong pointed out one problem with assuming that skills justify wages: "In most cases, we are not paid according to our productivity." When employers have greater bargaining power, workers may be underpaid. Many economists would agree that "relying solely on the wage-productivity-skill nexus doesn't make sense", says Prof Theseira. "It is really worth thinking about why we keep arguing cleaners must improve productivity to be paid more, but we don't question why we peg salaries in the civil service, or many administrative jobs, to the market benchmark and use that as the main justification for why salaries must go up," he added. Prof Ho identified a practical issue: "Ideally, PWM will see wages grow in tandem with skills and productivity but in reality, it is not always possible to continually raise productivity in some types of jobs." "We have to accept that in these instances, wages must still rise to keep pace with the rest of the labour market and the cost of living. Concepts such as minimum income standard can help to inform the societal consensus on wages at the lower end." He pointed to an existing policy lever: the local qualifying salary of S$1,400, which is how much a local employee must be paid to count towards the firm's workforce, in determining its foreign worker entitlement. As Mr Menon also noted, this could act as a "de facto minimum wage". Yet despite openness from some parts of the business community, it seems unlikely that the government will deviate from its approach - which, as reiterated by Mr Zaqy in March, is to have the PWM "on top of Workfare as the fundamental layer of support for our lower-wage workers".

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

Beyond the PWM, there lie larger questions of what it means to have "inclusive growth". Singapore must also consider the unemployed and those outside the labour market, such as retirees; and pay attention to affordability, and the availability of affordable options for housing, food, transport, healthcare and other public services and amenities, said Prof Ho. Prof Theseira sees inclusive growth as about "using policy to correct how the structure of modern economic growth in Singapore has tended to provide much higher rewards or returns to some of the most skilled workers, as well as to those who own investments in property and assets." Wealth inequality and social mobility are other issues to tackle for inclusive growth, he added. For Dr Ong, inclusive growth requires that "everyone has the opportunity to achieve their potential". Barriers to this include, for instance, inequality caused by private tuition: "The way the education system is structured, families who cannot afford tuition classes or enrichment classes are shut out of opportunities." In his National Day Message, Mr Lee closed his point on lower-wage workers by focusing on education, and providing opportunities "no matter where you start in life".

Even if and when people have opportunities to go as far as possible, however, there will always be workers at the bottom of the income ladder. The PWM and other measures will remain necessary to ensure that no matter where one ends up, it is still possible to make a living.

READ MORE:

- 'Real progress' for lower-wage workers is essential part of inclusive growth: PM Lee

- Appreciating work value equitably

- Some business leaders want a minimum wage to go with progressive wage model

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.