Circular economy key in battle against global warming

Recycling and composting is not enough to improve resource efficiency, says OVAM’s Christof Delatter

THE uncontrollable warming of our planet is all too often reduced to a problem of energy policy, which is a rather short-sighted approach, says Christof Delatter, interim secretary-general of the Public Waste Agency of Flanders (OVAM), which acts as the Flemish ministry responsible for waste management and soil remediation policy.

Flanders, Belgium has been one of the leading regions within Europe in setting out ambitious policies and targets on household waste management. OVAM is one of the founding figures of the Circular Flanders network, which brings together all societal actors that could play a role in the shift towards a more circular economy. It is also active internationally as a leading partner in developing an ambitious European and international policy.

Studies by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, which are also used as a basis for an analysis on the impact of material use by the region of Flanders, show that the consumption of resources causes more than 65 per cent of the impact in the form of greenhouse-gas emissions.

“Circular economy will therefore be key in the battle against global warming. We need a lot more resource efficiency than is the case now. Our resource footprint has to go down,” Delatter tells The Business Times (BT) in an interview.

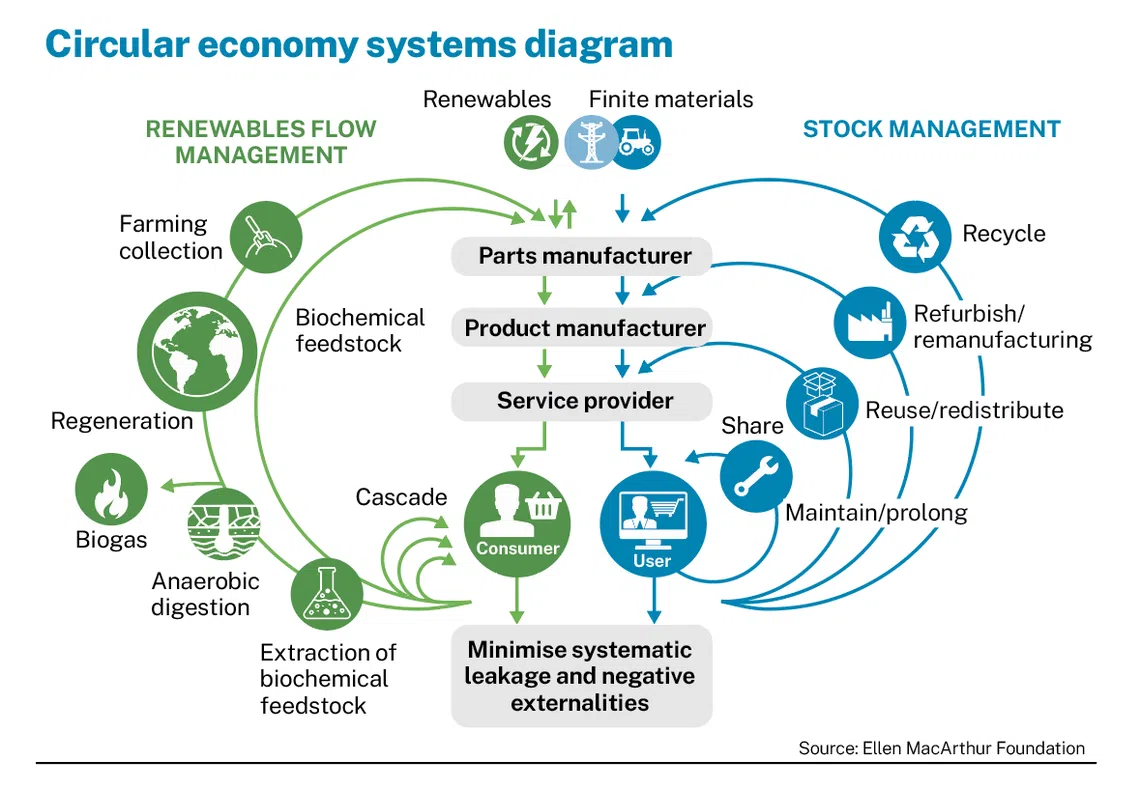

Asked what is a circular economy, Delatter refers to the butterfly diagram created by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Circular economy has a biological side and a mineral side, and there is a need to develop policies on both elements. In Flanders, there is already quite a good system of recycling and composting, as it collects almost 70 per cent of the household waste separately for that goal.

“However, the inner circles of the Ellen MacCarthur diagram are the key components. It is good to recycle and compost, but we need a real shift to more prevention, more sharing of goods, prolonging life expectancy of appliances, and more reuse and repair. Those are the key components,” he stresses.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

Delatter, an expert with almost 30 years of experience in waste management policy, says implementing a circular economy entails a clear choice of sharing of goods as this has a direct impact on a lower use of resources. “This also goes without saying, to a lesser extent, for maintaining goods and prolonging their life of use and for reusing goods for the purpose they once were produced,” he says.

“Recovering resources for remanufacturing and recycling avoids demand for primary resources. Product design is key for that. Every new product should be designed in such a way that it has a long-life span, that repair is an option, and that recycling can be done without harm to the environment.”

Key building blocks

“We far too often see new products containing substances of high concern. This is one of the biggest threats to circularity. For the biological feedstock, cascading the use of it can create different forms of carbon sinks, where we fixate carbon for longer periods and where we avoid turning it into carbon dioxide in our atmosphere.”

SEE ALSO

As for the key building blocks of a circular economy, he tells BT that there is a need to focus on product design. “In my opinion, every product designer should first work in the remanufacturing and recycling sector for at least 6 months. It is stunning that even in these days, we still see products that have short life spans, that you cannot dismantle in order to repair or recover components. New products still far too often contain dangerous chemicals, which has an impact on the recyclability of the materials after use.”.

“Eco-design – design for repair, design for recycling – is a condition for circular economy. Different instruments should be used to favour eco-design. Producer responsibility and internalising the environmental cost of a product in its price can give an incentive for better and more eco-design, supporting the transition towards a circular economy.”

At the same time, there is a need to measure the progress towards building a circular economy. In Flanders, Circular Flanders has created a Circular Economy Monitor for the region of Flanders. The monitor looks at more than 100 indicators to assess how far the model has progressed in Flanders.

“It starts from a top layer of macro-indicators giving insight in the consumption of materials, water, soil and space. A second layer links to the needs in housing, food and water, consumer goods and mobility. Adding figures for certain specific products or services gives a representative sample of daily consumption. All of these indicators give an idea of the level of circularity in our economy and the evolution of that in time,” Delatter tells BT.

‘Every penny for the right goal’

Green financing, in his opinion, also shows a clear shift where financial institutions clearly favour circular and climate-friendly approaches when supporting industrial investment. This should also apply to government subsidies and policies – high prices for fossil fuels should be seen as an opportunity to speed up the phasing-out of their use; rising costs for resources should trigger a policy that looks at more resource efficiency.

“Every penny should be used for the right goal, regardless of whether it comes from government or private financing,” says Delatter. “I realise that it is not always easy to clearly define what the right investments are. Should we support recycling of certain plastics, when phasing out their use might be a better option? Governments and scientific institutions should cooperate worldwide on gathering knowledge on these questions.”

Governments, development banks and commercial banks all have a role to play in green financing. To Delatter, it is logic that taxpayers’ money should only be used for circular and sustainable goals, focusing on a just transition. Development banks can play an important role in developing nations, supporting the right policy choices.

Policy decisions in many of those countries in the next decades might have an important impact on reaching certain climate goals (or not). Commercial banks can give a strong signal to the private sector by clearly favouring sustainable investment.

But again, financial institutions will need the support of universities, researchers and knowledge institutions in making the right choices, he tells BT.

Can green financing pay for waste management and recycling efforts?

“There was a strong debate on the European Union level on the so called taxonomy for sustainable activities: what activities can be accepted as sustainable so that investors, financial institutions can make the right choices and avoid the trap of greenwashing. This debate was, as could be expected, characterised by strong lobbying from different industrial sectors. I believe that our sector has to be exemplary and clearly should promote the inner circles of the Ellen MacArthur butterfly diagram. Those are the activities that should always be favoured in green financing,” says Delatter.

“I also see a great need for financial support for better waste management in general, especially in developing countries. The environmental gain of 1 euro (S$1.41) spent on waste management in those countries might have much more effect than a similar investment in a region with high separate collection rates. Climate change and resource scarcity are global problems, and should be addressed globally,” he adds.

“Waste management policy has a direct impact on the everyday life of every citizen. It defines the simple decision taken in every kitchen of which bin to throw a certain product in once it has been used,” he tells BT. “We try to influence what is put on the market. We work on individual behaviour – at home, in the office, or while being outdoors.”

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.