Amid growing anti-foreigner sentiment in Japan, Hamamatsu still welcomes foreign talent

Experts fear that Japan is at a tipping point

[HAMAMATSU (Shizuoka)] He was a wide-eyed 24-year-old when he first stepped onto Japanese soil in 1998, barely able to speak a word of the language. Now, Dr Binu Lal Sadanandan has built a life in Japan and witnessed the country’s evolving demographic landscape.

He took a leap of faith when he decided to pursue a PhD in geosciences at Shizuoka University, arriving in a pre-smartphone era with no easy access to online maps and translation apps, and fuelled by a fascination with a country known for its anime, omotenashi hospitality and monozukuri craftsmanship.

Now 51, the Indian national has spent more than half his life in Japan, where he is a permanent resident working at asbestos analytics start-up Alfred, based in the central Japan city of Hamamatsu. He has a 15-year-old son with his Vietnamese wife, an interpreter whom he met in Japan.

“My wife did not want to move to India, nor I to Vietnam, and we both felt Japan was a better place to raise our child,” he told The Straits Times (ST), adding that their son is enrolled in a Japanese school.

When Dr Sadanandan came to Japan in 1998, there were 1.25 million foreign residents, or less than 1 per cent of the then population of 126.4 million.

They now number nearly four million, making up 3.21 per cent of the population of 123.3 million as at June 2025, according to the latest government figures on Oct 10. In just six months, the foreign population grew by 187,000 people.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

Currently, the top 10 territories the foreigners come from are China, Vietnam, South Korea, the Philippines, Brazil, Nepal, Indonesia, Myanmar, Taiwan and the United States. While India does not feature in this list, Japan is now making a concerted push to woo skilled talent, like Dr Sadanandan, from the South Asian country.

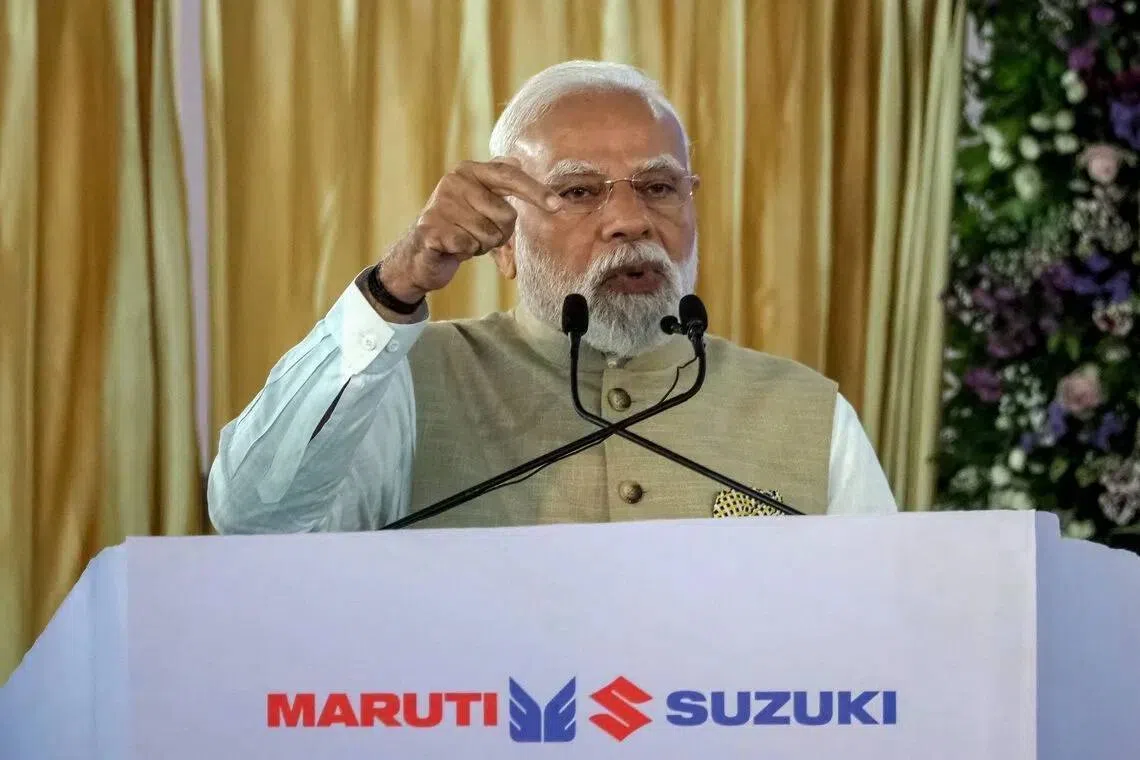

Under an agreement inked between Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba and his visiting Indian counterpart Narendra Modi in August, 50,000 people are set to arrive in Japan over five years.

This is despite the fast-growing ranks of foreign residents, alongside record numbers of inbound tourists, that have made foreigners significantly more visible in a society that views itself as homogeneous. Xenophobic and anti-foreigner attitudes have already surfaced.

Experts fear that Japan is at a tipping point. There is still no semblance of an official immigration policy, with generations of conservative ruling Liberal Democratic Party politicians preferring to ignore the contentious issue.

Now, they might be tempted to overcompensate, with the issue of foreigners having been weaponised by the far-right Sanseito, with its populist “Japanese First” platform, en route to huge gains at the Upper House election in July.

Traditional and social media amplify bad behaviour by bad sheep among foreign residents and tourists, highlighting crimes and disrespect for culture. An influx of foreign money has also been blamed for pushing real estate prices beyond the reach of the average Japanese household, thus fostering “us-versus-them” mindsets.

Dr Sadanandan admits to feeling concerned, telling ST: “Foreigners must realise they are guests in their host country. Rather than behaving like they would at home, they should respect cultures and feelings, and act accordingly.”

Most jobs in Japan are concentrated in metropolitan areas – and that is where most foreigners reside. The top five prefectures with the largest foreign population are Tokyo, Aichi (where Nagoya is located) and Osaka, with Kanagawa and Saitama in the Greater Tokyo region completing the list.

But many smaller cities and municipalities across Japan are likewise foreigner-friendly.

The Shizuoka prefecture city of Hamamatsu, an industrial heartland located 90 minutes from Tokyo and Osaka via bullet train, is home to 30,892 foreign residents spanning 90 nationalities. This is nearly 4 per cent of its population of 779,453 people, a proportion that surpasses the national percentage.

Like many other cities, it has suffered from incognito complaints from what experts attribute to those who feel emboldened by shifting political winds and the anonymity afforded by the internet or phone.

Hamamatsu is standing firm in its belief that given Japan’s economic and demographic realities, having more foreigners in its midst would only benefit the country. One in three of its foreign residents hails from Brazil, and it has set its sights on wooing more Indian talent.

Other local governments across Japan, from bustling metropolises to rural towns, are also welcoming foreigners.

After the July election, the National Governors’ Association, noting that unfounded claims about foreigners are heightening public anxieties, said in a statement: “We strongly urge the government to take responsibility and work towards accepting foreign nationals and realising a multicultural society.”

On Sep 30, Tokyo launched an International Residents Support Centre in its bid to attract more highly skilled foreign talent, as part of ambitions to become a global financial city. Services are free of charge, and its five staff accompany individuals to provide on-site assistance on the typical stumbling blocks of housing, banking and administrative issues.

Kouji Fujimura, director for global financial city promotion at the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, told ST: “There are some political parties that are expressing harsh opinions about foreigners, but we will not be influenced. We must continue to do what we need to do.”

Over in the Hokkaido town of Yoichi, home to wineries such as Domaine Takahiko, whose pinot noirs fetch more than S$3,000 a bottle at Michelin-starred restaurants in Singapore, mayor Keisuke Saito told ST that foreigners who can contribute are more than welcome. Foreigners are already volunteering at Domaine Takahiko during harvest season.

“As an island nation, Japan has had a long-time allergy to foreigners. But we now need thorough national discussions to formulate proper policies to ensure economic vitality,” the 43-year-old said. “I’m Japanese and I will naturally put Japan’s interests first. But because of that, I’m happy to welcome anyone who can contribute to the country.”

Foreigners leave their mark

In 2023, the government-linked National Institute of Population Policy and Studies forecast that foreign nationals will exceed 10 per cent of Japan’s dwindling population of 87 million in 2070.

However, Kansai University of International Studies visiting professor Toshihiro Menju, who studies immigration policy, believes foreign resident numbers will likely hit 10 million – and account for 10 per cent of the population – by the 2040s, or 25 years sooner than official estimates.

Already, the indelible impact of foreigners on Japanese society is pronounced. The ratio in healthcare, for instance, was one foreigner per 634 Japanese in 2014, but that figure surged to one per 79 in 2024. In construction, the ratio soared from one foreigner per 246 Japanese, to one per 27. In fisheries, it climbed from one foreigner per 99 Japanese, to one per 19.

“Yet, Japan only has a stealth immigration policy, owing to the longstanding taboo. For a long time, there have been right-wing politicians who insist that Japan has a mono-ethnic population and is unsuitable for foreigners,” Professor Menju said.

Associate Professor Yasutaka Saeki, an expert on intercultural studies at the Shizuoka University of Art and Culture, agreed that the government’s long-time reluctance to openly discuss immigration policy has sowed distrust.

“People used to ignore the presence of foreigners because of their limited numbers. But now, the rising numbers of residents and tourists have made them impossible to ignore,” he told ST. “Diversity should be a strength. Rather than focusing on the downsides, such as frictions that will inevitably arise, we must think of how this can help revitalise Japan’s economy and society.”

With most foreigners living in metropolitan areas, Prof Saeki said Hamamatsu’s experience could be a case study for other mid-tier cities and rural areas that are grappling with the question of multiculturalism.

Wooing India

Hamamatsu has a long history of innovation – it was where the world’s first television image was projected in 1926, and today, is where start-up EX-Fusion aims to achieve the world’s first commercial laser-powered nuclear fusion reactor.

It is home to companies such as carmaker Suzuki Motor and Yamaha, known for its musical instruments and motorcycles. With Toyota Motor based nearby, Hamamatsu also has a concentration of vehicle component-makers.

This industrial environment drew an influx of Brazilians in the 1990s, after Japan revised immigration laws to allow South Americans of Japanese descent to relocate to Japan as residents. Nearly a century before, many Japanese had migrated to flee domestic poverty and unemployment.

Yusuke Nakano, 55, who in 2023 became mayor of his hometown, said: “It is true that in the early days, there was friction between communities. The problem was insufficient information on how to live in Japan, including such issues like garbage disposal. The lesson learnt was that close communication on a regular basis was crucial for multicultural integration.”

Over the decades, Hamamatsu has rolled out a slew of community initiatives to foster assimilation, including by offering tuition to foreign children and subsidies for Japanese education support for foreign workers.

Hiroko Kato, a 77-year-old resident, told ST: “It now feels so natural to be living with foreigners in (our) midst. It makes me sad, looking at the state of Japanese politics.”

The city holds regular international celebrations, like an annual two-day India Festival in September that featured ethnic food and performances, as well as activities from cricket to yoga. Suzuki’s chief executive Toshihiro Suzuki attended that event.

Nakano stressed that everyone is welcome: “It’s not about taking away jobs from the Japanese.”

While there are today just 675 Indian residents in Hamamatsu, the city aims to grow its ties with the South Asian country. In August, it entered a “friendship city” pact with Ahmedabad in western India to foster the exchange of human resources, following a separate agreement in 2024 with the Indian Institute of Technology Hyderabad over the recruitment of talent.

In 2027, an international school with an Indian operator is set to open in Hamamatsu, with Nakano recognising this as necessary to attract highly skilled Indian talent and their families.

When asked why the emphasis on India, Nakano told ST: “India was where the number ‘zero’ was discovered; it has many talents with science and engineering backgrounds that we need as a manufacturing hub.”

He added that Hamamatsu already shares a strong affinity with India through Suzuki, which first invested in the then state-owned Maruti in 1982 before raising its stake and making it a subsidiary in 2002.

Suzuki has such deep roots in India that in 2022, Modi attended the 40th anniversary celebrations of the company’s foray into the country. In August, he attended the launch of Suzuki’s first battery electric vehicle, which was made in India.

As it is, Suzuki’s Indian-made models such as the five-door Jimny Nomade and Fronx have proven so popular in Japan that the company is second only to Mercedes-Benz in terms of imported vehicles to Japan from April to September 2025, according to Oct 6 data from the Japan Automobile Importers Association.

Suzuki’s managing officer Junya Kumataki declined to reveal details of its foreign workforce in Japan, citing confidentiality, but said the company was increasingly recruiting from Indian universities, with “more than 10 young engineers” joining in 2025.

In the past five years, the company has also recruited graduates from countries such as China, South Korea, Indonesia, Hungary, Nepal and Sudan.

To help them assimilate, Suzuki has begun a mentoring system, while company communications are sent in both Japanese and English. Given its burgeoning Indian workforce, Indian curry meals are also served at its in-house cafeteria, which proved such a hit that the company began selling four types of packaged vegetarian curries to the public on June 25.

Also in Hamamatsu are car parts manufacturers like Kunimoto Kogyo, which counts Toyota as a major customer for its lightweight metal pipes. Its 70 employees include two Filipinos, and president Kenji Kunimoto said he has his “antenna raised” over Hamamatsu’s ongoing efforts to draw Indian talent.

Another firm is FCC, whose clutches are found in one in every two motorcycles worldwide, with clients from Suzuki and Yamaha, to Harley-Davidson and Ducati.

FCC has seven foreigners among its 1,000 employees in Japan, including Praveen Sundarampillai, a 26-year-old engineer from India.

General affairs manager Shingo Iida told ST: “It is now getting more difficult to find talent. If we cannot hire, whether Japanese or from abroad, then our business operations will be affected.”

But he recognised the need to first create an environment that is more conducive to foreigners, with FCC taking “baby steps” by holding diversity meetings.

Sundarampillai, a graduate of Mahalingam College of Engineering and Technology in Tamil Nadu, told ST that he felt at home at FCC, bonding with his colleagues over their shared love for two-wheelers. While he cannot understand technical jargon in Japanese, his colleagues have been patient.

He first came to Japan in October 2022, first attending a language school in Tokyo before moving to Aomori, where he worked at the National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology. The self-professed bike-head then discovered his dream job.

“I love motorbikes very much, and anyone who is into bikes will know of FCC,” he said. “Now I enjoy spending my free time with my colleagues, going motorcycle riding in the nearby mountains. Everyone has been very welcoming.” THE STRAITS TIMES

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.