South-east Asia evolving into multi-hub industrial network: Roland Berger

Its vast reserves of critical minerals, and booming consumer market, could be the region’s strongest bargaining chip in a world hungry for both resources and growth

[KUALA LUMPUR] Low labour costs still attract manufacturers to South-east Asia, but the region is fast evolving into a network of specialised industrial hubs – minerals in Indonesia and the Philippines, mid-stream electronics in Malaysia and Vietnam, electric vehicle assembly in Thailand, and finance in Singapore.

The winners will be those who can choreograph this regional web by designing dual sourcing, embedding sustainability, and using Singapore’s re-export routes as tariff shock absorbers, according to a September report by business consultancy Roland Berger titled Asia’s supply chain reconfiguration.

“Once we change our mindset from competing to collaborating, ‘Made in South-east Asia’ won’t just be a label. It will be an advantage,” said John Low, co-managing partner for South-east Asia at Roland Berger.

He added that the region’s vast reserves of critical minerals, combined with a booming consumer market, could be the region’s strongest bargaining chip in a world hungry for both resources and growth.

The challenge now is transforming that advantage into real strategic leverage, particularly as global supply chains realign, he told The Business Times in an interview.

According to the report, regional integration and industrial relocation have shaped a multi-tiered Asian manufacturing ecosystem – Chinese technological leadership, South and South-east Asian production capacity, and Japanese-South Korean know-how.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

Together, this evolving structure could lift the region from its traditional role as the “world’s factory” into a coordinated network of cross-border industrial synergies, according to the report.

From rivalry to collaborations

Low noted that the region’s weakness is not capacity but fragmentation. “Many South-east Asian countries are offering the same semiconductor services. The question is: How do we work together to become a regional powerhouse instead of isolated players?”

The report supports his view. It identifies inefficient regional collaboration as one of Asia’s three systemic challenges, alongside overcapacity in low-end industries and weak foundations in high-end manufacturing. Without a clear supply chain leader, standards and strategies remain fragmented, delaying integration.

SEE ALSO

Low’s prescription is straightforward: collaborate more, compete smarter.

“We have a market of 750 million people. If I can source from within Asean rather than outside, I should give preference to my regional partners.”

He suggested common logistics and customs standards to make trade “as seamless and cheap as possible”, and for targeted fiscal policies that support reliability of power and transport instead of blanket tax breaks.

In the private sector, collaboration could be achieved as well. Take Malaysia’s Penang Automation Cluster (PAC) as an example.

PAC was established in 2017 by three of Penang’s most technologically advanced firms – ViTrox, Pentamaster and Walta Engineering – to serve as a one-stop precision engineering and metal component hub that supports multinational companies’ operation in Penang and Kulim in Kedah.

Low noted that each firm brings different strengths to the semiconductor chain and delivers complete solutions that are globally competitive.

Resources as bargaining chips

South-east Asia’s natural resources now sit at the heart of the region’s new bargaining power. The report noted that Indonesia, which holds 42 per cent of the world’s nickel reserves, is turning that advantage into a battery-cell industry expected to expand from 10 gigawatt-hours (GWh) this year to 140 GWh by 2030.

The Philippines ships out over 370 kilotonnes of nickel every year, and the country is also quickly growing its clean energy sources by 5 per cent annually.

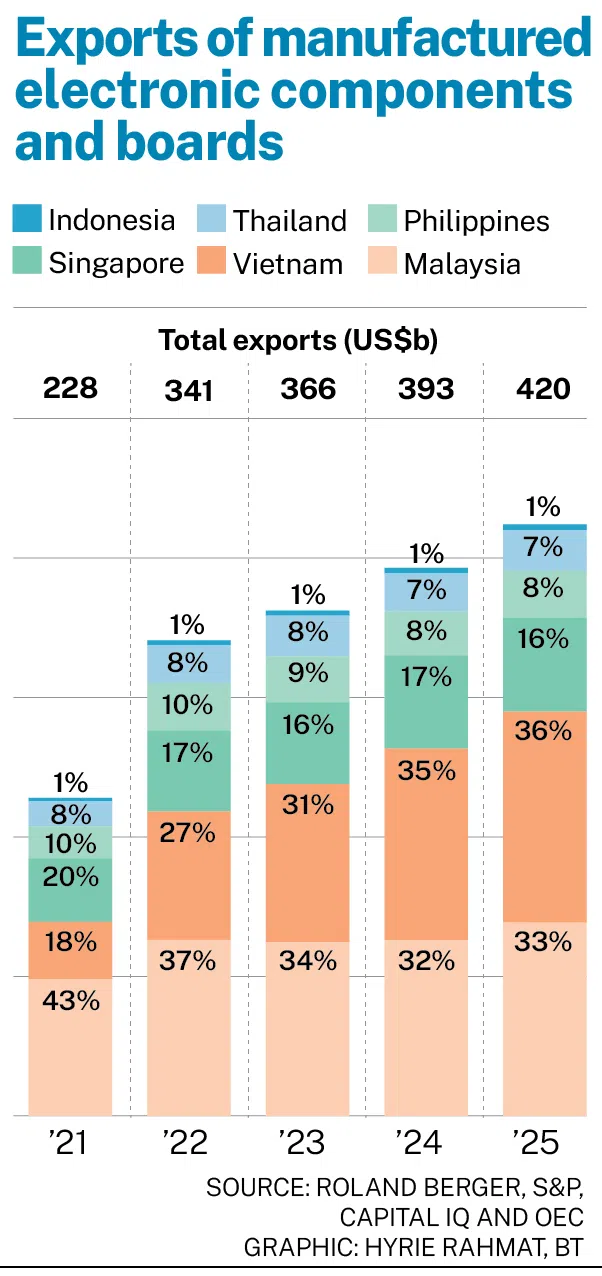

Malaysia, meanwhile, handles roughly a third of global outsourced semiconductor assembly and testing exports, and is channelling US$11 billion into new wafer fabrication capacity.

Low believes these advantages should be used to negotiate for technology transfer and joint research and development.

“It’s like the old barter trade: you buy my palm oil, I buy your machinery. We can leverage raw materials to secure training, knowledge and partnerships,” he added.

Such leverage could help address Asia’s weakness in mid to high-end manufacturing. By insisting on technology partnerships tied to resource access, South-east Asia can climb faster up the innovation ladder rather than remain stuck in low-margin assembly work, said Low.

Infrastructure and logistics: the critical enablers

For regional collaboration to work, both goods and data must move freely. Logistics and infrastructure will be “game changers”, said Low, pointing to Malaysia’s East Coast Rail Link and transnational corridors linking Singapore, Thailand and China as anchors for the next phase of integration.

The report highlights the same trend – regional integration under the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership is boosting component flows, with parts now moving from Batam to Binh Duong to Penang before a single export declaration is filed.

Shipments linked to Indonesia have grown 5.6 per cent a year since 2019 to exceed US$106 billion – a “living diagram of Factory Asia knitting itself tighter”.

Even so, bottlenecks persist. Indonesia’s logistics performance ranking remains low, Thai port customs are slow, and inland haulage costs in Vietnam are high.

Artificial intelligence-driven platforms now cover more than 70 per cent of logistics operators, but skilled-engineer shortages and high energy costs still limit automation. Low agrees: “Anything that helps the movement of goods and people – cheaper, faster, more stable – benefits everyone.”

Decoupling from US?

Low cautioned that South-east Asia cannot yet decouple from US technology.

“Short term – five to 10 years – no. Everything we use is embedded in US systems. But within 20 years, maybe less, it will happen,” he added.

Roland Berger’s report similarly highlighted China’s climb up the value chain, through initiatives such as Made in China 2025 and the “dual-circulation” model.

As China localises more high-end production, South-east Asia’s role becomes that of partner and hinge – hosting capacity that complements, rather than competes with, China’s push into advanced manufacturing.

Low noted that China, Japan and South Korea will anchor the high-tech layer. “South-east Asia can supply what they lack, such as resources, manufacturing scale and market access, and in return, we learn.”

He said the region should push for joint innovation tailored to local needs. Products built for Japan or the US may not fit Asean markets; co-developed versions can leapfrog the innovation gap while embedding local firms in global supply chains.

Malaysia’s reboot

Low acknowledged that Malaysia has fallen behind some of its neighbours, citing political volatility that has turned investors cautious. However, he believes Malaysia can regain its footing by building on its solid semiconductor base and widening its industrial footprint beyond Penang.

Strategic projects, such as industrial developments in Carey Island and the East Coast Rail Link, could improve logistics and attract new investment, while the Johor–Singapore Special Economic Zone offers a blueprint for cross-border synergy.

“Singapore has world-class R&D but lacks land and resources; Johor can offer midstream manufacturing and high-skilled jobs,” Low said.

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.