‘We survived to 100’: Ho Kwon Ping on Banyan Group’s homecoming with Mandai resort

It is looking at potential conversions under its Dhawa brand in Singapore and acquisitions of small management companies

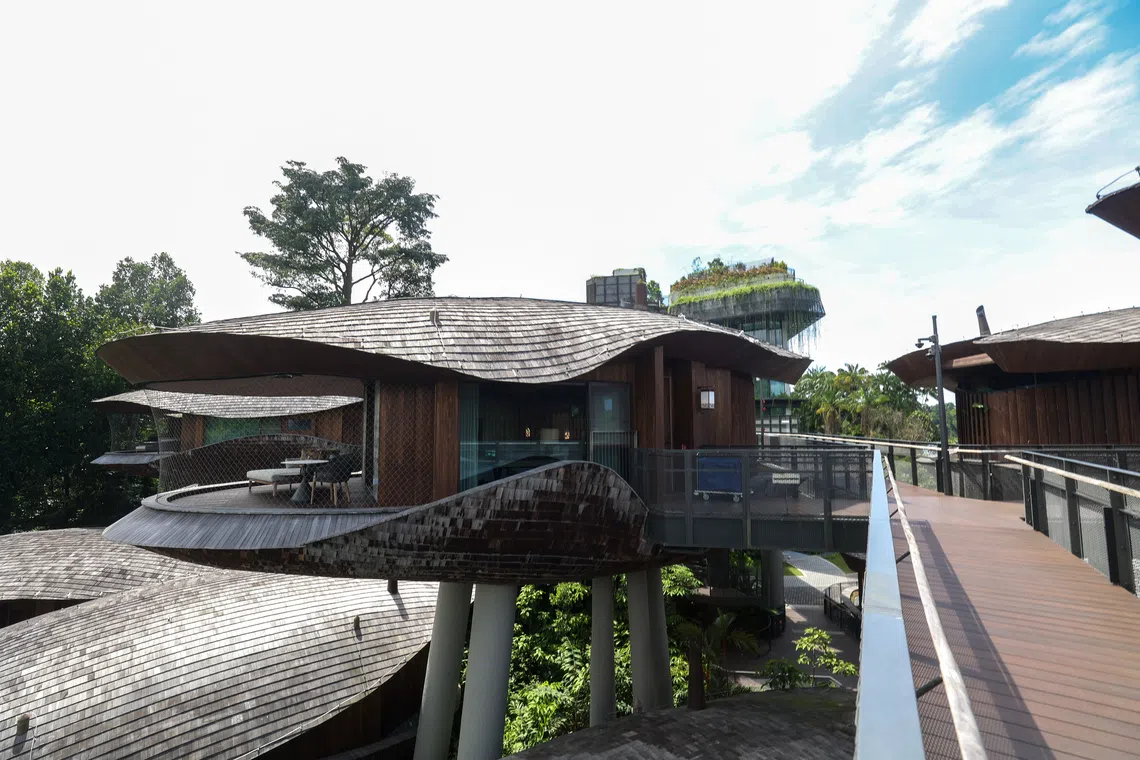

The strategies and stories that shape today’s leaders. [SINGAPORE] When Banyan Group officially opened its 100th property – the Mandai Rainforest Resort by Banyan Tree – in November, the occasion was marked by a grand celebration, with a visit by President Tharman Shanmugaratnam, a gala dinner and a festival.

But for founder and executive chairman Ho Kwon Ping, 73, the opening was not just a moment of triumph, but one of great relief.

“It’s more like beating our chest, to say: ‘Phew, we survived to 100’. Not, ‘How great we are, at 100’,” he told The Business Times in an interview. “When you go from zero to 100, that’s almost necessary for survival.”

Ho has previously described Banyan Group’s journey as one of an antelope crossing a river, wary of the crocodiles that could snap it up before it reaches the far bank. Reaching 100 hotels is like finally crossing the river, and exploring what the other side has to offer.

The next steps forward will focus on quality, not quantity.

“I don’t think 200 hotels or 300 will ever be a (goal),” Ho said. “We definitely don’t want to ever set for ourselves a numbers game.”

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

Innovating for felt needs

Banyan Group’s origins are well documented. In the 1980s, Ho and his 75-year-old wife – Claire Chiang, who became a co-founder – acquired a plot of land in Phuket, only to learn that it was an abandoned tin mine not fit for habitation.

However, after years of rehabilitation, they opened Laguna Phuket, a self-contained resort destination. Still, one parcel of land remained unappealing to operators because it lacked a beach. To counter this, the first Banyan Tree property, pioneering the all-pool villa concept, was created.

These are now a dime a dozen, Ho pointed out. “So you have to keep on innovating.”

The new resort in Mandai – Mandai Rainforest Resort by Banyan Tree – is a sustainability-oriented eco-resort facing a reservoir. This is in itself innovative within urban Singapore’s concept of resorts, Ho said, not to mention its innovative sustainability features.

These include guest rooms designed for natural ventilation, temperature regulation and water conservation, as well as solar panels, rainwater harvesting systems and wildlife-friendly lighting.

Ho believes that Banyan Group has proven its sustainability credentials.

But he also believes that a holistic approach to sustainability is needed.

“My personal bugbear is the fact that sustainability today seems to refer to only climate change and the physical environment,” he said, calling this interpretation “completely wrong”.

Instead, he believes it is about total social, economic and climate sustainability, and corporate governance and the way staff and shareholders are treated should all be considered.

“If you’re going to talk about sustainability, the word implies: What can last?”

From rainforest to city streets

Mandai Rainforest Resort by Banyan Tree also marks a homecoming for the homegrown hospitality group, which has never had a property in Singapore.

With the momentum created by having an “iconic” property, Ho believes that the impetus for other property owners interested in having Banyan Group manage their properties in Singapore will grow.

In Singapore, at least, Banyan Group plans to stick to its asset-light approach and keep its focus on management, rather than ownership. Currently, of the 100 hotels it manages, it only owns about 15 or so, most of them in places where land is cheap.

Opportunities for more luxury Banyan Tree-branded hotels, which are expensive to do in the land-scarce city-state, “are not going to be that common”, Ho said. But he sees opportunities for its other brands, particularly those designed with smaller rooms.

Its Dhawa line of hotels is designed to be contemporary and casual. Rooms in these hotels are about half of the size of those in Banyan Tree hotels. Existing three-star hotels in “very good locations” such as Chinatown and business areas could be converted under this brand, making them “much more contemporary, much more design oriented, much more suitable for a sophisticated clientele”.

Entry-level Folio, with its micro-hotel concept and rooms measuring just 16 to 18 square metres, could also be well-suited for Singapore.

Multi-brand, but shared ethos

In the first place, the group diversified its offerings partly to provide options for collaborations with hotel owners, when opportunities came, but were not suitable for the luxurious Banyan Tree brand.

There is a commonality in the brands’ DNA, not just operationally, but in its ethos and emphasis on sense of place, he said.

Branding has always been intentionally a key source of strength for Banyan Group, a takeaway from the disadvantages of the family business Ho inherited from his father, a contract manufacturer that “had no branding whatsoever”.

And economically, many famous independent hospitality brands were too narrow in scope and were ultimately acquired.

“I’m determined to be independent, and if you’re determined to be independent, you need to have a more diversified revenue base, customer base and everything else,” Ho said.

Diversification also makes a company more resilient – a valuable trait in hospitality. Compared with other industries, it is one of the most influenced by event risks, whether they are natural disasters, political problems, geopolitical tensions, or health scares, noted Ho.

On whether guests can expect more brands, Ho said “never say never” – but it is early days yet for some, and the group may have to “wait and see” which take off, which need help, and maybe even reconceptualise.

A global POV

Banyan Group now has a “conceptual difference” in its growth strategy.

Rather than one hotel at a time, it is looking at buying over small management companies, which could mean acquiring 15, 20 management contracts at one go. Under this arrangement, Banyan Group takes fees to handle the daily operations and offer its management expertise.

After more than three decades, the group now has the management capability and depth to absorb such a large-scale acquisition and digest it, he said.

And with the growth of its branded residences segment – Banyan Group is the single largest branded residences developer in Asia and fourth globally – its financial wherewithal has increased enough to support inorganic growth.

Within Asia, Banyan Group is “growing quite fast” in Japan and sees potential in Indonesia, not just for its luxury clientele but also its mid-scale brands, given the large population.

It is also going to open new hotels in Tanzania and Lapland – “from an Asian point of view, very exotic places”.

Ho credits his global upbringing as one reason Banyan Group has been able to operate in more than 20 countries.

Born in Hong Kong, he lived in Thailand, Taiwan, and the US, before coming to Singapore to enrol in National Service.

“I was completely an outsider. I was a banana. I was an Asian in America,” he said. And while this identity crisis made him feel vulnerable, it also gave him an advantage: “Because you don’t closely identify with anything parochial, you’re actually more open to unusual environments.”

Rather than thinking like an American, a Singaporean or a Chinese, his thinking was based on what he calls his “weird background”. “Therefore, nothing that I encounter which is new is all that new to me.”

Family and legacy

Chiang and several of the couple’s children are involved in the running of Banyan Group. But the accidental hotelier – as Ho calls himself – had not opened his first resort with the ambitious dream of building a family empire.

“We didn’t have a clue what we were doing,” he said, calling the endeavour “a stab in the dark”.

“Then it was this growing realisation that perhaps it could be something that my wife and I would like to put our life towards.”

Ho and Chiang’s children, having grown up with the business, have seen what their parents have done with it and share their values.

Their oldest son, Ho Ren Hua, is chief executive officer of agri-food company Thai Wah, the original family business; their daughter Ho Ren Yung and younger son Ho Ren Chun have taken up senior management positions in Banyan Group.

But he added: “I don’t want to fool ourselves into thinking that if we keep on as a family business, or that all my children, my grandchildren, offspring, are the best people to manage the business.”

Managing a family business is a responsibility to protect the business, not a place to grandstand, he said.

The advantages of Banyan Group being a family business is that it has its values, and a long-term view. But family members in the next generations do not always need to be management.

Citing Warren Buffett, Ho said: “How many children of Olympic athletes become Olympic athletes themselves?”

Three questions with Banyan Group founder Ho Kwon Ping

Q: Was there a pivotal moment in your career or personal life that changed your approach to leadership?

Probably when I was kicked out of Stanford, and I could have gone on to Cornell, or I could have come back to do National Service.

That was the first time in my life when I had to make a decision which was very uncomfortable for me – to uproot myself from a very comfortable lifestyle in the US as a student activist, to come back and do NS in a country I had never lived in before.

Leadership is not oratorical skills. It’s not rallying people to do things. The source of leadership is your own ability to detach yourself from your own feelings and make a decision which is right, but is personally difficult to make.

Q: What is one piece of “unconventional wisdom” you swear by that most business schools would tell you is wrong?

Ditch due diligence and do what your intuition tells you to do. Because if I had done my due diligence, I would never have bought Laguna Phuket. Also, keep Asking Why, incidentally the title of one of my books.

I think too many people, particularly in Singapore, perhaps because of our schooling system, are told what to think. We’re not told how to think. Teaching someone how to think – critically, with independence – is very important for leadership, entrepreneurship and everything else.

Q: When you feel burnout creeping in, what’s your non-business-related “panic button” activity or routine that reliably resets your focus?

Whenever burnout creeps in, I go to nature. Many of our Banyan Tree resorts are surrounded by nature, like here in Mandai. Sit here, look around, and you can de-stress and tune out everything.

Learn the principles and the stories that shape today’s leaders. Get more of The Leadership Playbook here.

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.