Will the AI bubble pop in 2026? Why South-east Asia won’t shake if it does

In South-east Asia, AI startups raised over US$2.3 billion as of June 2025

Will the AI bubble pop in 2026? It’s one of the hottest questions going into the new year.

The implications are enormous for South-east Asia and India, with governments and companies in these regions investing heavily in the tech across software, enterprise platforms, robotics, and infrastructure.

In South-east Asia, AI startups raised over US$2.3 billion as of June 2025. Money has been pouring into data centres and infrastructure projects: For instance, Malaysia alone saw almost US$2.7 billion in infrastructure investments in the first half of 2025.

In the US, however, the stakes are higher. AI-related stocks accounted for roughly 44 per cent of the S&P 500’s value, which corresponds to about US$25.5 trillion in market value.

Tech in Asia reached out to founders and investors to ask about the possibility of a bubble bursting in 2026. While most were concerned, few thought that any fallout from a downturn in AI would be catastrophic, and none of them believe that artificial intelligence is a passing fad.

The concerns focused on a few common themes: expectations running ahead of reality, costs rising faster than revenue, and a growing dependence on capital markets to keep the system afloat.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

At the same time, most also see reasons for optimism, especially in South-east Asia. If a global AI bubble does deflate, they believe the region may feel the impact later and less violently than the US. As a result, South-east Asia will emerge with a more disciplined industry focused on execution rather than hype.

Does it exist?

Is there even a bubble to begin with?

It depends on how you define a bubble and which component of the AI stack you look at. There’s the model layer, which refers to the large, general-purpose AI systems that require massive amounts of computing power to train and operate. Then there’s the application layer, which comprises the products and services built on top of AI models.

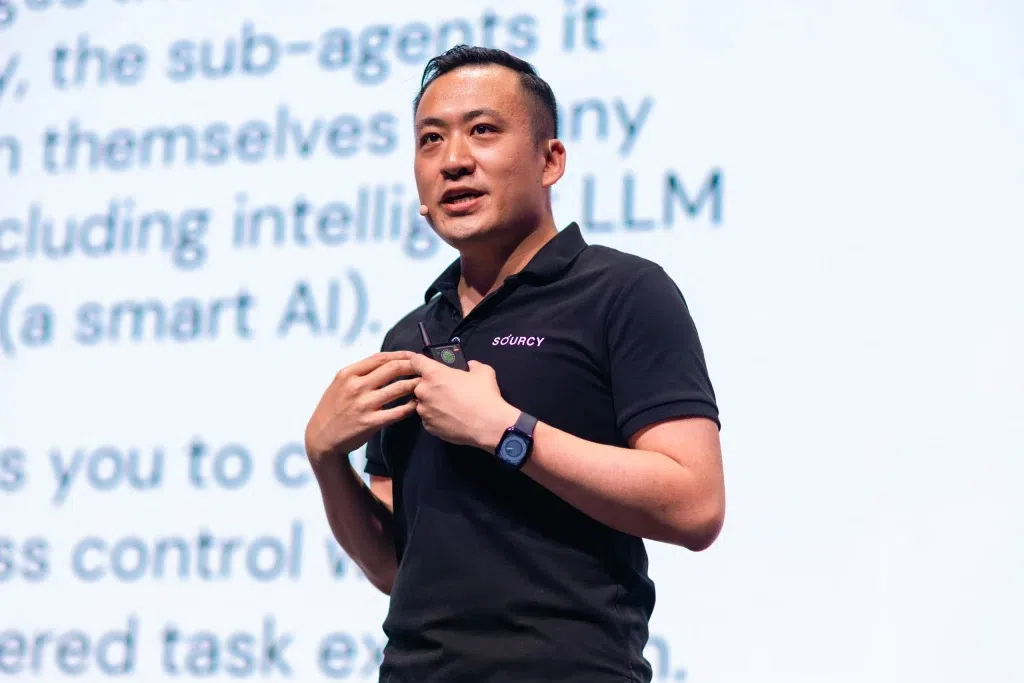

“The question is not whether these models are valuable – they clearly are – but how many years the capital markets can continue subsidizing this cost structure,” says Karl Chan, founder and CEO of Sourcy, an agentic AI firm that helps companies source products.

At the model layer, Chan sees clear economic strain. Training and running frontier models – the industry shorthand for the most advanced systems available – costs hundreds of billions of US dollars a year. Much of that cost is currently absorbed by investors rather than customers, with many companies competitively pricing themselves out of profitability.

At the application layer, Chan’s view is far more optimistic. He thinks that most industries are still figuring out how AI can replace manual workflows with automation that can save time and money. If application companies succeed in delivering those gains, the value created could eventually justify the costs upstream.

The application layer is also largely dependent on companies using frontier models on a subscription basis or developing open-source versions, both of which cost considerably less than creating a model.

“At the application level, though, we’re still barely scratching the surface of real use cases,” Chan adds.

That distinction between layers is echoed by Partha Rao, founder and CEO of Pints.ai, an AI business intelligence company based in Singapore.

Rao is concerned about a valuation bubble in parts of the market, “especially where pricing is running ahead of proven revenue and deployment maturity.”

But he draws a line between financial excess and technological progress: A correction in valuations would not erase the underlying utility of AI systems already being used.

“Sometimes you need the bubble to pop in order for prudence to set in,” he says.

Willson Cuaca, co-founder and managing partner at East Ventures, takes a similar position from an investor’s perspective. He regards AI as a foundational technology, not a standalone industry.

While he is confident about the long-term adoption of the tech, he is still cautious about hype-driven valuations. He explains that the danger comes when expectations are allowed to outrun what the technology can reliably deliver in the short term.

“We are closely monitoring areas where the intense hype and fast rise in valuations, driven partly by the high costs of building advanced models, may be outpacing the short-term delivery capacity of the technology,” Cuaca says.

Expectations and reality

Most executives Tech in Asia spoke to think there is a widening gap between what AI is perceived to be capable of and what it can actually do.

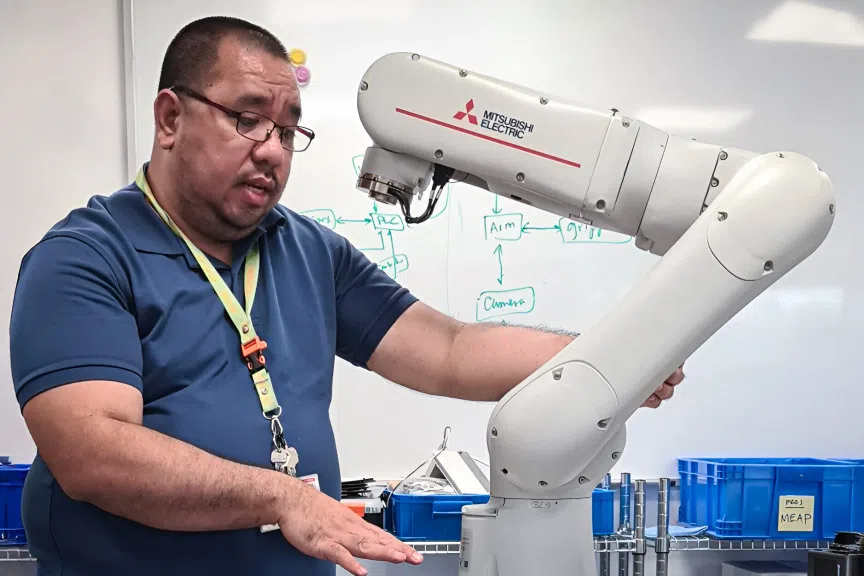

This gap is especially visible where AI and robotics intersect, says Albert Causo, CEO and co-founder of One Hand Robotics. The two are often treated as interchangeable, leading customers to assume that advances in AI automatically translate into more capable robots.

As a result, his team frequently has to explain that many desired capabilities are either not technically feasible yet or are possible only at a cost that makes them impractical.

That mismatch risks eroding confidence in AI. While the tech can already deliver improvements in certain tasks, repeated disappointment across industries could lead to a broader loss of trust.

Amit Verma, founding head of technology at Neuron7, sees a similar dynamic playing out in enterprise software. He observes that many organisations are buying AI tools because they feel pressure to keep up, not because they have a clear understanding of how those tools will generate returns.

The ease of building early prototypes with large language models, he adds, can be misleading. Turning those prototypes into reliable, scalable products still requires significant engineering effort – something many teams underestimate.

“Somehow, unit economics has taken a back seat,” Verma says. “AI or no AI, if returns don’t materialise, it’s all theatrics.”

Datature CEO Keechin Goh also cites underdelivery as a central risk, noting that many AI tools fail to live up to their marketed capabilities, particularly once they are tested in real operating environments.

With the high costs of computing power, cloud services, and specialized talent, a company can drain cash quickly if customers fail to convert from being pilot clients to long-term contracts.

In July 2025, MIT’s Project NANDA reported a 95 per cent failure rate in enterprise AI initiatives, despite substantial investments – estimated at between US$30 billion and US$40 billion – in generative AI this year.

How a correction could start

While opinions on timing vary, most of the people that Tech in Asia spoke to agree that any correction would likely begin quietly rather than with a stunning collapse.

Verma of Neuron7 expects early signs to emerge in the second half of 2026 if organisations begin tightening budgets and demanding clearer returns on their AI investments.

The hardware and infrastructure layer is a potential pressure point, Verma says. Today’s demand for high-end chips assumes that AI training and deployment will continue to accelerate indefinitely. If companies realise they can achieve acceptable results with fewer resources, orders for expensive hardware could slow sharply.

Goh of Datature does not expect the burst to be a “single dramatic event,” either. Instead, he foresees “multiple cracks showing over time, leading to a potential negative loop.”

One Hand Robotics’ Causo and Pints.ai’s Rao both argue that what lies ahead is more likely to resemble “a balloon deflation rather than a bubble pop.” In their view, clients will gradually recalibrate expectations and scale back overly ambitious projects, but they will continue to adopt AI where they think it can be of use.

“AI (and robotics) can already deliver on certain things, just not on all,” Causo says.

South-east Asia’s position

On the question of regional impact, almost everyone that Tech in Asia spoke to believes that South-east Asia is less exposed to a violent AI correction than the US.

Chan of Sourcy argues that startups in the region are already accustomed to operating under constraints. High costs and limited access to capital have pushed many teams towards open-source models, self-hosted infrastructure, and efficiency-focused design.

A global pullback, he says, would accelerate trends that are already underway.

East Ventures’ Cauca agrees, pointing out that AI adoption in South-east Asia has been pragmatic rather than speculative. He says that any downturn would likely result in a “flight to quality,” with investors favouring well-governed companies that can demonstrate real revenue and defensible business models.

But the region still faces some risks. Goh warns that pre-revenue startups and companies attempting to replicate US business models without adapting to the local market would be particularly vulnerable.

Demand in adjacent industries such as data labeling and annotation work, much of which is based in South-east Asia, could also fall quickly if AI spending slows.

Causo notes that sectors such as business process outsourcing and robotics could face short-term delays as companies reassess spending. But he believes the region’s caution could ultimately serve as a buffer, limiting overreach and preserving confidence.

The AI aftermath

So what happens after the bubble bursts?

According to Verma, even if valuations fall, trained talent, data centres, software infrastructure, and institutional knowledge will remain. As with previous technology cycles, that foundation could support a healthier phase of growth once expectations realign with reality – similar to what happened following the dot-com crash.

Verma anticipates consolidation, with stronger firms acquiring weaker ones at discounted valuations.

“A correction will not kill AI – it will make it healthier,” he says. TECH IN ASIA

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.