Luxury brands cut price of exclusivity as Chinese spending drops

Premium-goods consumers – typically professionals in urban centres or younger generations in rising cities – are tightening their belts

ON A recent spring afternoon, models paraded Louis Vuitton’s latest collection inside the French brand’s Beijing flagship store, to the clink of champagne flutes and polite applause from a select batch of clients.

These private fashion shows – known as VIC, or “very important client” events – were once reserved for only the biggest spenders. Today, they are being deployed by luxury brands more often, and the bar to entry is lower.

“These events usually used to be for customers spending at least 500,000 yuan (S$90,130) a year,” says Liu Yu, a luxury goods enthusiast. “I’ve spent just around 100,000 yuan per brand, and I was still invited twice in one week in March.”

Such VIC events, which are widely shared on Chinese social platforms like Douyin and Xiaohongshu, are part of a growing effort by luxury brands to chase waning demand.

These shifts are emblematic of a cooling in China’s once-thriving luxury market as premium-goods consumers – typically professionals in urban centres or younger generations in rising cities – are tightening their belts.

A market in retreat

The Chinese mainland luxury market shrank by up to 20 per cent in 2024, according to projections by Bain & Co in a January report, ending a short-lived post-pandemic recovery.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

This is in part due to more people spending abroad instead, with Chinese purchases in Japan and across Asia now exceeding 2019 levels. Yet, total global luxury spending by Chinese consumers is still down around 7 per cent from a year earlier, and 16 per cent below pre-pandemic levels, according to the report.

“Interestingly, while VICs have demonstrated greater resilience, they have also become more conservative in their luxury spending, opting to diversify their wealth across a broader range of assets during this economic downturn,” Bain analysts said.

At the heart of the pullback is a shift in consumer psychology. Many Chinese middle-class families aren’t necessarily poorer, but they are increasingly risk-averse.

Job insecurity and asset value losses are all weighing on how people perceive their financial future, said Lisa Hu, a partner and managing director at consultancy AlixPartners.

Consumers are choosing to sit on their cash instead. Chinese central bank data shows a record 17.99 trillion yuan in new deposits in 2024, with household savings accounting for nearly 80 per cent. An AlixPartners survey in January found middle-income earners in second-tier cities, Gen Z buyers in major metros, and high earners in towns are all cutting back on luxury spending.

“Before, we could rely on younger shoppers to make up for the drop-offs in spending,” said one luxury executive. “Now, even they are not buying.”

Feeling the chill

No segment is immune. Watches and jewellery – often considered investment pieces – are taking the hardest hit. Bain estimates that watch sales in China are down as much as 33 per cent in 2024, with jewellery slipping by up to 30 per cent.

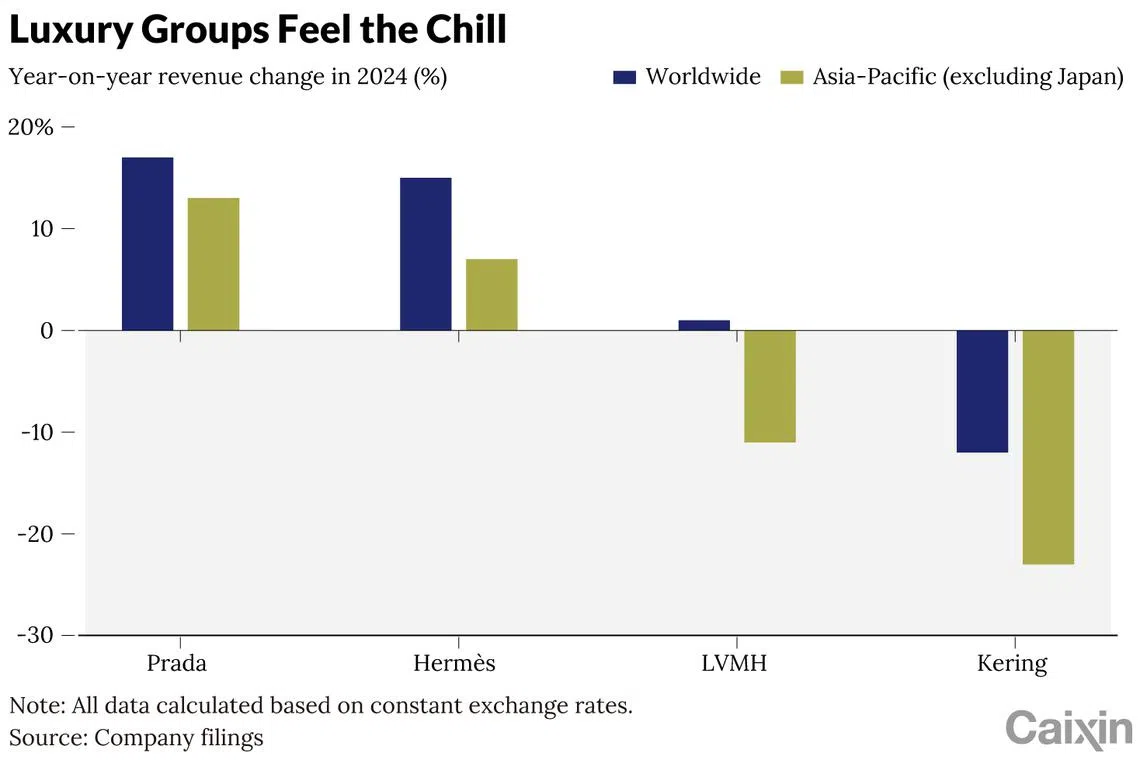

Swiss giant Compagnie Financiere Richemont, owner of Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels, reported an 18 per cent year-on-year sales drop in Greater China in the fourth quarter of 2024. LVMH’s watch and jewelry division fared slightly better, down 2 per cent globally, but sales in Asia excluding Japan were down 17 per cent.

Watch lovers like Yang Mushi, who once saw timepieces as assets, are now holding back.

“There’s always a voice in my head saying that it’s better to keep the cash in hand,” he said. Secondary market prices for high-end watches have fallen, undermining confidence in their value retention, said Yang, who operates a second-hand watch business.

Jewellery demand has also dried up. Shen Feng, a seller, said many of his biggest clients have stopped buying diamonds and other precious stones for the past two years. “Diamonds don’t have a reliable resale benchmark like gold does, so people hesitate,” he said.

Even fashion and leather goods, the industry’s core, are sliding. Leather bag sales in China dropped up to 25 per cent in 2024, while apparel and accessories declined up to 20 per cent, according to Bain. Gucci’s sales in Asia-Pacific slumped 32 per cent, while Yves Saint Laurent’s dropped 21 per cent, according to parent company Kering.

Two of luxury’s most resilient names – Hermes and Chanel – seem to be weathering the storm better. Hermes reported 14.7 per cent global sales growth, though its Asia-Pacific growth slowed to 7 per cent from 19 per cent a year earlier.

Brands like Hermes and Chanel feature exclusivity and have strong brand discipline, said Pablo Mauron, a managing partner of marketing firm Digital Luxury Group’s China region. They focus on their VICs and are less affected by changes in the spending power of the middle class, he said.

“Even when middle-class buyers scale back, they still want to buy ‘the best’ if they buy at all,” said Gao Ming, a senior vice-president at communications firm RF Thunder China.

New strategies to grow sales

Despite the downturn, no brand is pulling out.

At the China International Import Expo last November, LVMH, Kering, Tapestry and other giants reaffirmed their long-term commitment to the Chinese market.

Josie Zhang, president of Burberry China, said the company will keep investing in the country and introduce more products and services tailored to local consumer needs. Alfonso Dolce, global CEO of Italian luxury brand Dolce & Gabbana, echoed those plans, saying that the company is looking to expand its operations in China and deepen customer engagement.

But brands will have to get creative to compete. Many brands are experimenting with new tactics – expanding into smaller cities, adding new hybrid experiences, prioritising customer engagement, and innovating digitally.

American brand Coach, for instance, opened its first fourth-tier city location in Daqing (in Northeast China’s Heilongjiang province) in 2020, followed by another in Baoji (in Shaanxi province) in 2022. The brand is not about being exclusive or selective, but “close to where our customers are”, said Yann Bozec, Asia-Pacific president of parent company Tapestry was quoted as saying in a Reuters interview then.

Demand for luxury goods is shifting from first-tier cities to emerging lower-tier markets, said Ma Jintao, a partner at consulting firm Kearney. In smaller cities, the relatively low cost of living gives affluent residents stronger purchasing power.

Smaller cities such as those of second and third tiers are “showing vitality due to population migration, which is boosting consumption power in both volume and average selling price”, the Bain analysts said in their report. “This presents a new battlefield for luxury brands seeking first-mover advantages.”

Other innovations include hybrid retail experiences. Coach opened its first Coach Coffee Shop in Shanghai last April, and a Coach Apartment in Nanjing that merges fashion, food and furniture. Last month, Prada opened its first stand-alone restaurant Asia in the historic Rong Zhai mansion in Shanghai.

Brands are also adapting to the evolving preferences of high-net-worth clients.

“Some prefer to shop from home for privacy and convenience. Others seek unique experiences like at luxury hotels, golf courses, or iconic landmarks,” said Tina Zhou, CEO of Yaok Institute, which conducts research and provides consulting services for luxury brands.

Luxury brands would need to overhaul their retail system around personalization, she said. This shift raises the bar for sales personnel – demanding stronger interpersonal skills, deeper product knowledge, and better customer acquisition capabilities.

Brands’ digitalisation strategies will also be key, Zhou said, but it must go beyond merely launching accounts on e-commerce platforms.

“Technologically, opening an e-ecommerce shop is no longer a barrier,” she said. “The real challenge lies in the fact that there’s no platform in China where high-net-worth individuals naturally gather. This makes it difficult for luxury brands to reach their target customers effectively online.”

In fact, many brands still struggle with sustainable digital engagement. For example, Hermes’ WeChat Mini Program saw its monthly active users swing wildly between 120,000 and 9.24 million in 2024, while Gucci’s ranged from 200,000 to 1.2 million, according to QuestMobile data.

Still, some brands believe the best shopping experience is offline. A senior executive at a luxury group said the company is now prioritising bringing customers back to brick-and-mortar stores and enhancing the in-store experience.

She added that in a volatile market, it is even more important for luxury brands to stay the course.

“When foot traffic in malls declines, we should proactively guide customers back offline. We cannot chase short-term sales by offering discounts online,” she said.

“Also, the drop in sales over the past year should be viewed in light of the high base in 2023. We will need another couple of years to see clearly where things are headed,” she added. CAIXIN GLOBAL

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.