100 Years of Solitude: Magic fades in TV adaptation

Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s lush novel resists Netflix’s noble efforts to recreate its beauty

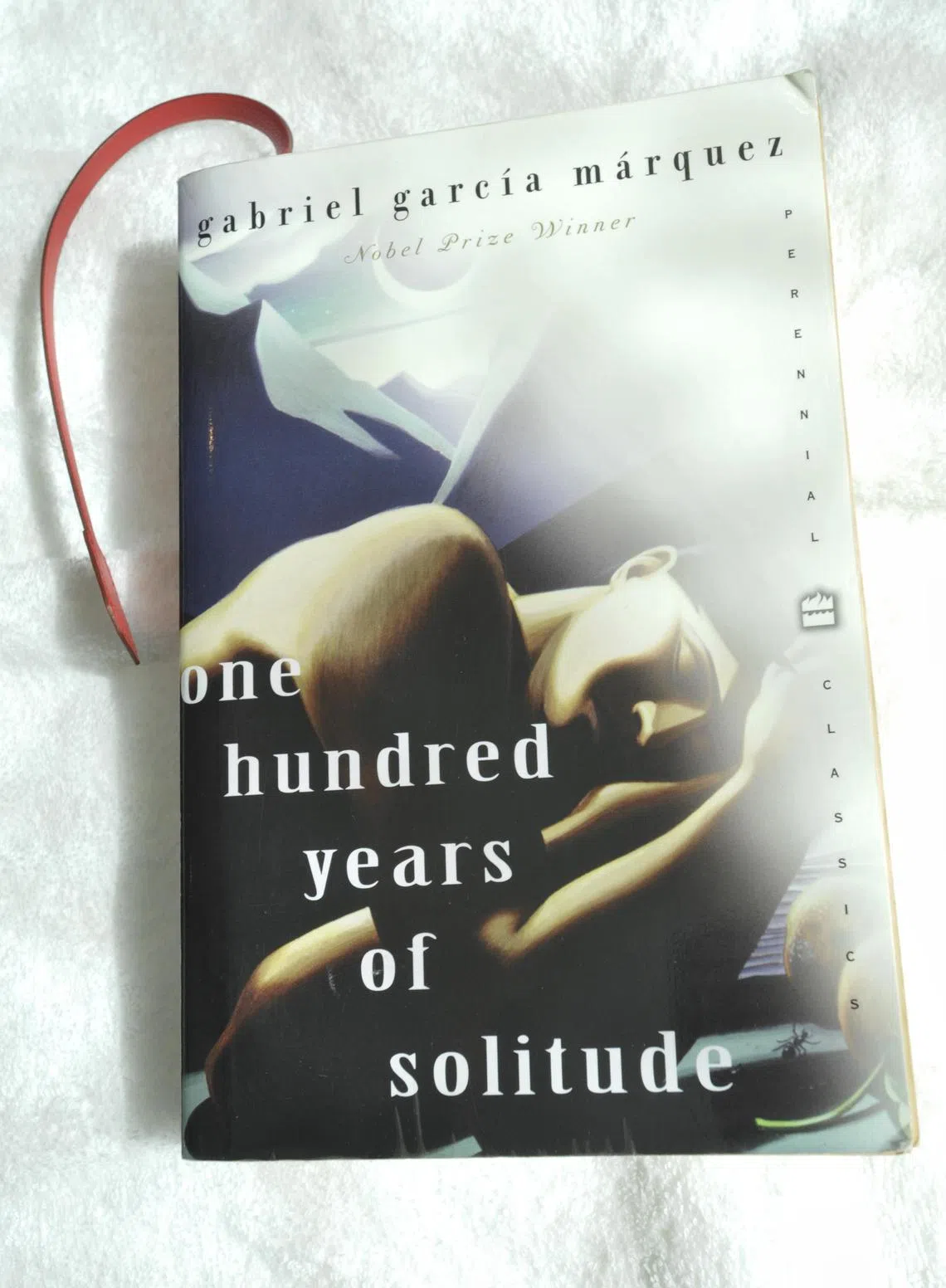

THERE was a stretch of time, somewhere between the 1970s and 1990s, when nearly everyone who loved world fiction was reading the 1967 novel 100 Years of Solitude by Colombian writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

It was so epic, so surreal, so unlike anything they had ever read at that point, it felt like discovering an entirely new way of understanding stories. Even though the Latin American writers had begun writing in the style known as “magical realism” since the 1940s, not many readers outside of the continent had had much exposure to it.

For these readers, Garcia Marquez’s novel about the Buendia family in the mythical town of Macondo wasn’t just a story book. Reading it felt like a communal, mystical, even religious experience. Here, blood can flow out of a dying man’s body and snake its way knowingly through the streets to reach his mother’s house and announce his death while she is making bread in her kitchen.

A beautiful young woman can ascend to heaven while she is simply hanging laundry. Rain can fall for four years, 11 months and two days, while the rest of the world carries on as if nothing strange is happening.

Because so much of the history and behaviour of the characters are grounded in human truths, the mystical and magical always feel believable – making the story mesmerising.

Over the years, many TV, film and theatre producers had approached Garcia Marquez for permission to adapt the story for the screen or stage. But the writer turned down every offer, believing that his own novel was “unfilmable”.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

In 2014, Garcia Marquez died, and it was only then that his family agreed to an adaptation by Netflix. His sons, Rodrigo and Gonzalo, serve as executive producers to ensure its faithfulness to the source material, with Alex Garcia Lopez and Laura Mora roped in as directors.

Netflix has now released the first eight of 16 episodes, shot in Colombia and starring Colombian actors. It’s easily the most expensive production in the country’s history, and reportedly contributed more than 225 billion Colombian pesos (about S$70 million) to the country’s economy.

Is it faithful? Yes, very much so. Every important scene from the first half of the book is recounted here in some detail. Is it as lush and magical as the book? No, unfortunately not. Is it worth spending over eight hours watching the series? Again, no. You’re better off reading the novel – even if you haven’t read anything longer than 100 pages since you left school. (The book is about 420 pages long.)

Although much effort has been put into building the mythical town of Macondo on a 540,000 square metre plot with the help of 150 artisans, the results are somehow underwhelming. 100 Years of Solitude thrives on the magic of Garcia Marquez’s prose. HIs ability to conjure wondrous images using only words has a kind of genius no amount of physical recreation could replicate.

In the novel’s famous pages that narrate the dying son’s blood flowing out of him to wind its way to his mother’s home, Garcia Marquez writes: “A trickle of blood came out under the door, crossed the living room, went out into the street, continued on in a straight line across the uneven terraces, went down steps and climbed over curbs, passed along the Street of the Turks, turned a corner to the right and another to the left, made a right angle at the Buendia house, went in under the closed door… and went through the pantry and came out in the kitchen, where Ursula was getting ready to crack thirty-six eggs to make bread. ‘Holy Mother of God!’ Ursula shouted.”

In the screen adaptation, this extraordinary scene is depicted simply and with far less inspiration, losing much of the mystical wonder and ambiguity. Garcia Marquez’s lush sentences and poetic images are ultimately constrained by the limits of dialogue and action – the need to look “real”.

Then there is the matter of narrative structure. 100 Years of Solitude thrives on telling its story in a non-linear, cyclical way that underpins the seven-generation history of a family doomed to repeat itself. On page, these intricate timelines blur together like a dream. But on TV, the structure is simplified so the story can be told in a more linear and digestible fashion.

Sure, some complex novels have been successfully adapted for the screen, from Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings series to Denis Villeneuve’s Dune saga. But in the case of 100 Years of Solitude, Garcia Marquez was right to think that his prose is best left in the realm of the imagination for now. There, its magic can flourish unbound.

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.