Grieving? Heartbroken? Uzbekistan’s Bukhara Biennial might heal you

The country’s first major international art show offers some balm for a hurting world

[BUKHARA] There is no shortage of heartbreak. From personal loss to collective grief, from mourning a loved one to witnessing the relentless toll on civilians in Gaza, Sudan and Ukraine, sorrow is everywhere. Every day, our screens deliver images of bombed cities, flooded towns and street protests – a grief we consume helplessly.

Amid this tide of pain, a new art biennale in Central Asia offers something rare – not distraction, but healing.

Recipes For Broken Hearts is the title of Uzbekistan’s first major international art event. Staged in the historic city of Bukhara, whose old centre is a Unesco World Heritage Site, the Bukhara Biennial is as much a meditation on our shared humanity as it is an art exhibition.

Take, for instance, the work of Munisa Kholkhujaeva, a 27-year-old Uzbek artist. In a courtyard of a centuries-old school, she has created a meditation garden with potted plants and metallic sculptures, produced in collaboration with craftsman Anton Nozhenko.

Visitors are invited to pause, reflect and sit with their pain. Her three-part work also includes a tea room where visitors can sip herbal tea and share their stories of loss.

“I wanted to create a space where grief can be acknowledged, not rushed,” Kholkhujaeva says. “Pain does not vanish – but it can transform into a form of wisdom, a tenderness that connects us to others.”

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

Global artists, local traditions

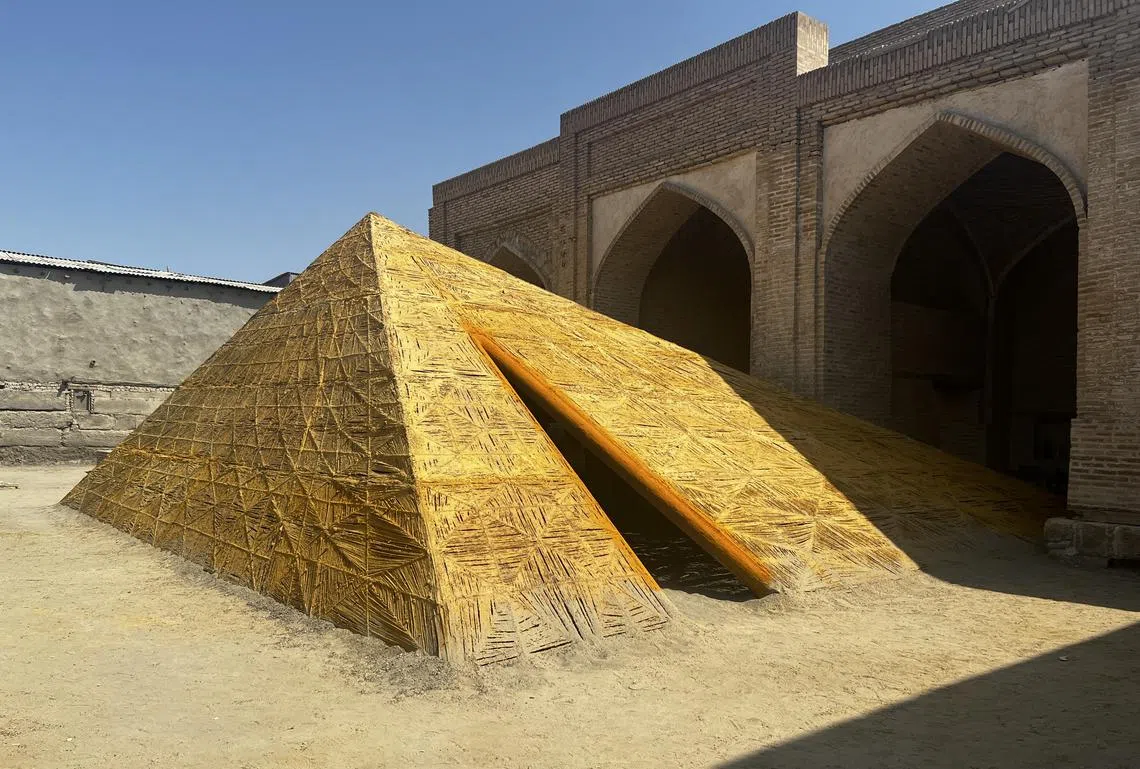

Her installation is one of more than 70 site-specific works placed in Bukhara’s caravanserais, madrasahs and mosques. The biennale brings together over 200 artists and artisans from 39 countries, among them famous British sculptor Antony Gormley and Uzbek restorer Temur Jumaev, who co-created a courtyard filled with blocky human figures made from mud and straw – symbols of vulnerability and resilience.

Elsewhere, acclaimed Indian artist Subodh Gupta has constructed a house from enamel pots and pans, and ceramic plates made by craftsman Baxtiyor Nazirov. On some days, Gupta cooks and serves a meal for visitors inside it, in the belief that “food is art, food is memory, food is healing”, he says.

Food is woven across the biennale whose title, Recipes For Broken Hearts, comes from an Uzbek legend: Ibn Sina, the father of early modern medicine, is said to have created the popular rice dish plov to console a lovelorn prince.

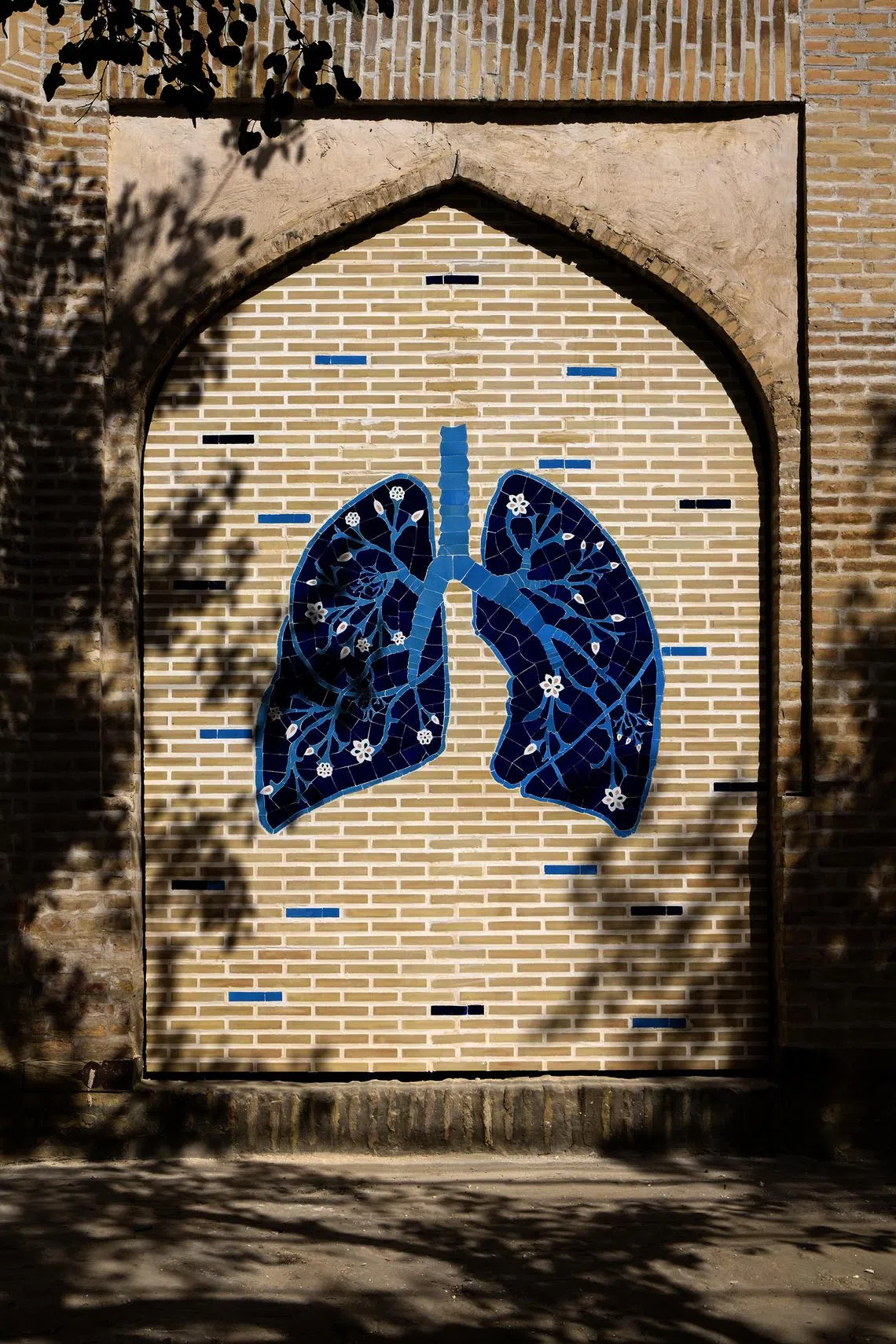

Other works draw on different beliefs. Uzbek artists Abdulvahid Bukhoriy and Jurabek Siddikov have transformed a former prayer room into a luminous ocean-like chamber, where a brass-and-copper fish sculpture hangs suspended overhead. In Central Asia, fish are believed to absorb illness and bring calmness.

In a speech delivered to the people of Bukhara, the biennale’s curator Diana Campbell said: “When something like a heart breaks, there is beauty found in what we rebuild. A biennale cannot heal the many heartbreaks in our world today… but perhaps we need to reimagine biennales not as exhibitions that simply display art, but as vehicles that can actively contribute to creating the conditions where great art and great artists can flourish.”

Buried kimchi and borrowed time

Several pieces unfold slowly, like rituals of duration. The Buddhist nun-chef Jeong Kwan has buried pots of kimchi in clay, to be unearthed at the biennale’s closing – a quiet reminder that healing takes time. Kholkhujaeva’s potted plants may wither and die, echoing grief’s lingering presence.

Healing from heartbreak is a process, Campbell adds. “This biennale highlights works that honour the slow unfolding.”

Even the buildings themselves take part. At Khoja Kalon Mosque, craftsman Bakhshillo Jumaev and his wife Mukkadas Jumaeva partnered with Belgian designer Hana Miletic to repair cracks in the mosque facade with golden threads, inspired by the Japanese art of kintsugi. Under the Bukhara sun, the gilded seams glint faintly like a healing balm, a physical metaphor for the biennale’s ethos: brokenness embraced, not hidden.

The choice of Bukhara is not incidental. During the Timurid Empire, the city hosted legendary gatherings that fused creativity with feasting. Campbell calls the biennale a modern echo of those 14th-century celebrations, which featured “an abundance of art, music, poetry, dance and, of course, food, that could extend for as long as three months”.

The biennale is also part of a larger plan to restore Bukhara’s historic centre. Streets have been pedestrianised, caravanserais refurbished, and brickwork repaired to host exhibitions.

“Our aim has been twofold: to protect the historical fabric and to give the spaces a new, useful life,” says Gayane Umerova, chairperson of Uzbekistan’s Art and Culture Development Foundation.

This dual mission – preservation and reinvention – turns the city itself into a living museum. The restored spaces, once in danger of becoming tourist cliches, are now animated by installations, performances and community gatherings.

Uzbekistan’s cultural renaissance

The Bukhara Biennial, however, is just one part of Uzbekistan’s larger goal of transforming itself into a creative hub. In the capital city of Tashkent, the Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA) is preparing to reopen later this year under the leadership of Sara Raza, a well-known curator who previously worked at the Guggenheim and Tate Modern.

Housed in restored buildings including a former tram depot, the CCA will host residencies, exhibitions and research programmes designed to connect international artists with Uzbekistan’s history and tradition.

“Given that over 60 per cent of the country’s population is under the age of 30, creativity becomes a very active pathway,” Raza says. “It’s a way to enable workforce development, influence curricula, and support this next generation in creative thinking, problem-solving and self-expression. Uzbekistan has a deep tradition of artistry and craft. We’re not approaching it from nostalgia – we’re thinking about it as part of the future.”

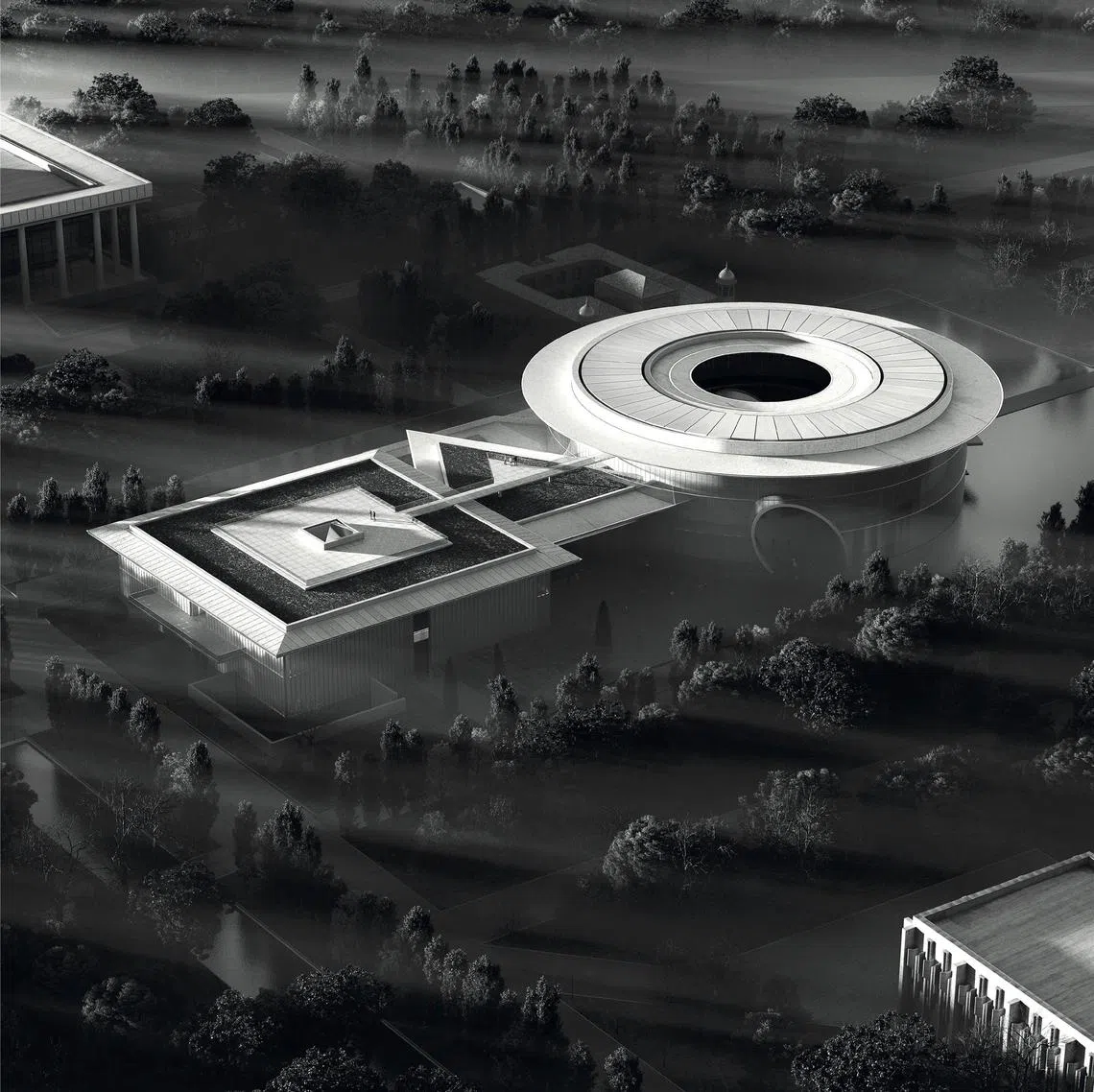

In August, Uzbekistan broke ground on the Tadao Ando-designed National Museum, set to open in March 2028. The distinctive structure will cover 40,000 square metres and house more than 100,000 artefacts. President Shavkat Mirziyoyev calls it “a majestic symbol of the new Uzbekistan”, designed to “reflect our revitalised cultural potential”.

Observers say these initiatives are not vanity projects. As a former Soviet republic, Uzbekistan treads carefully in the shadow of the Russia-Ukraine war, while also sharing a volatile border with Afghanistan. Investing in local culture is as much about soft power and social cohesion as it is about art.

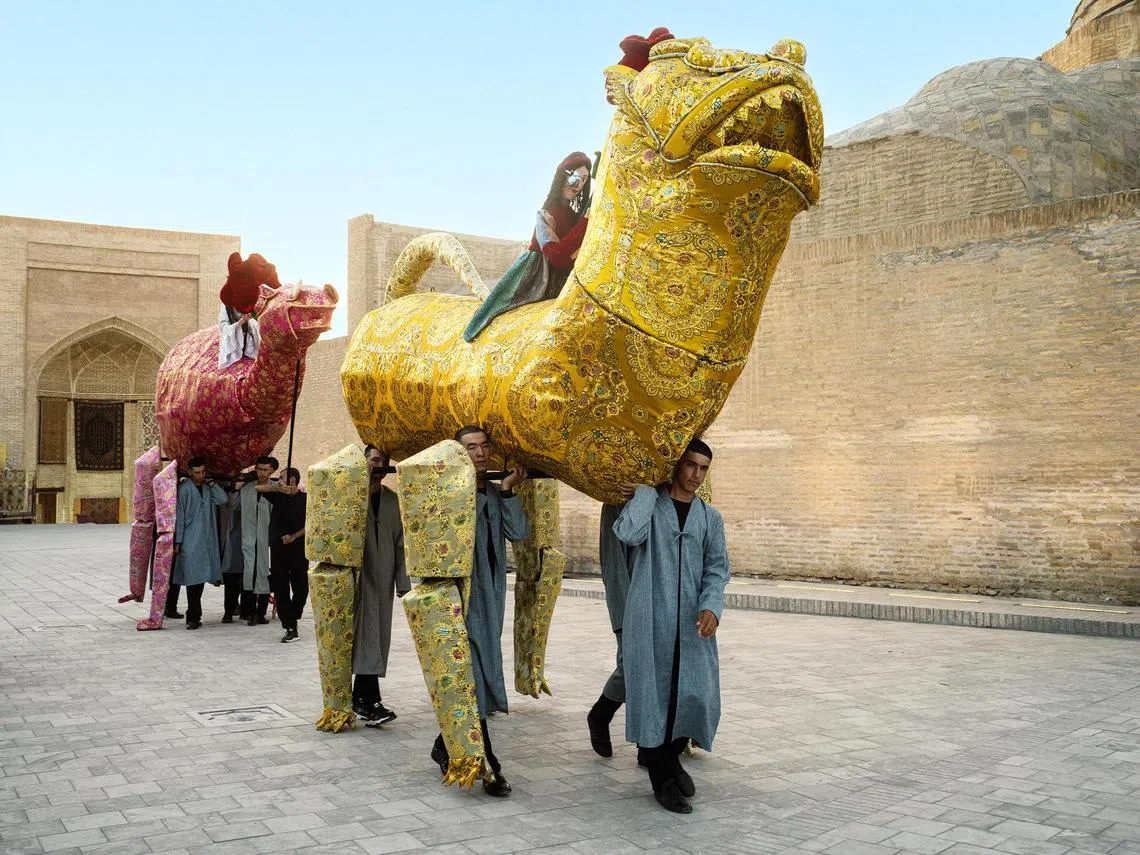

“Central Asia is reasserting its voice on the global stage,” Umerova said in an interview with The Astana Times. “Not as a periphery, but as a serious nexus for art discourse.” The biennale’s decision to credit craftsmen alongside artists underscores this point. Ceramics, textiles, metalwork and puppetry are not relics of the past but living practices, equal to contemporary art.

The economic dividends are real. Hotels in Bukhara are seeing a boost in enquiries, as international press coverage brings the city new visibility. For a country with a large youth population, this matters. A creative economy is a stabilising force, offering opportunity, fostering pride and countering the pull of emigration or radical ideologies.

Collective healing

As the sun set on the biennale’s opening weekend, thousands of Bukharans crowded the town square to share steaming bowls of plov, cooked in vast cauldrons by chefs Pavel Georganov and Bahriddin Chustiy. Families and students perched on steps and walkways, eating and chatting as the city turned the act of dining into a collective artwork of its own.

In two months’ time, more chefs will gather here for the Rice Cultures Festival, cooking plov, paella, pulao and jollof side by side – a culinary metaphor for solidarity across borders.

As Campbell sees it, the biennale is a “relational form of exhibition, like a feast, a concert, or a parade” – an event designed for collective experience.

And that may be the Bukhara Biennial’s biggest achievement yet: turning art into a shared ritual of mourning and mending, while simultaneously positioning Uzbekistan as a cultural innovator.

In a fractured world, this ancient Silk Road city has offered something both humble and ambitious – a reminder that beauty and brokenness can co-exist, and that healing, like art, takes time.

The Bukhara Biennial runs from now till Nov 20, 2025. Admission is free.

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.