Milan Design Week: Singapore talents create human-centred, sustainable solutions to contemporary issues

Five designers at the world-renowned event talk about their works

[SINGAPORE] As global talents converge at the most important design event in the world this week, national design agency DesignSingapore Council (DSG) is returning to it with a bigger lineup.

In its third appearance under the Future Impact series at Milan Design Week, DSG is exploring the nation’s evolution through the lens of design.

Instead of the six and seven designers of the past two years, Future Impact 3: Design Nation will feature 14 Singapore talents – from established names to up-and-coming ones – who will reimagine design’s role in shaping people’s lives and the world around them.

Curated by Tony Chambers, Maria Cristina Didero and Singaporean co-curator Hunn Wai of industrial design consultancy studio Lanzavecchia + Wai, the three-part showcase kicks off with a segment highlighting design’s integral role in nation-building over the past 60 years.

This is followed by eight works from local designers focused on design-driven, sustainable and human-centred responses to contemporary issues. The final segment showcases Singapore as a global design hub nurturing forward-thinking talent.

In Wai’s experience, taking part in such events has given him valuable exposure to global audiences, dialogues and collaborators, which have shaped both his practice and perspective as a designer.

“Milan Design Week is unlike any other design platform,” says Wai, who had a “truly transformative” experience exhibiting there in 2008, after graduating with a master’s degree from Design Academy Eindhoven in the Netherlands.

“It’s not just an exhibition – it’s an ecosystem. The cross-pollination of disciplines, cultures and industries there is electric. For young designers, it’s a rare opportunity to have their work seen, critiqued and celebrated by the international design community. Being there accelerates growth, deepens perspectives and creates connections that can catalyse a career in powerful ways.”

We speak to five of the designers to find out more.

Supermama

This design studio and store is known for creating and curating house ware and souvenirs reflecting Singapore’s multicultural identity. It is presenting Kintsugi 2.0, which reimagines the traditional Japanese art of repairing broken ceramics with lacquer mixed with gold.

Supermama’s modern version extends the craft to objects with missing pieces by using gold-plated 3D-printed resin to reconstruct and restore, rather than merely repair. This preserves its form and blends sustainability, craftsmanship and technology.

“3D printing enables us to accurately recreate or completely reimagine what’s lost, giving us the choice to restore a piece’s history or introduce a new narrative,” says John Tay, its lead designer. “We do this in a way that preserves the spirit of craftsmanship behind the original art form. While algorithms apply the structure to the missing parts of the porcelain precisely, the intricate patterns are fully directed by the designer, not left to the machine.”

The works displayed are Supermama’s One Singapore 2024 plate, where missing icons are reconstructed and held together by a skeletal lattice structure; and a traditional vase revived using a generative batik pattern filling in the unknown artwork of its missing section. The generative batik design was created via algorithms inspired by the repetitive motifs found in traditional batik and Peranakan elements in Singapore’s architecture.

“We see design as a soft skill, one that helps us understand and empathise more deeply,” says Tay. “From there, we can create more thoughtful, human-centred solutions.”

Olivia Lee

An internationally acclaimed multidisciplinary designer, the Central Saint Martins graduate has done work for clients such as Hermes, Cartier, Vacheron Constantin and Samsung.

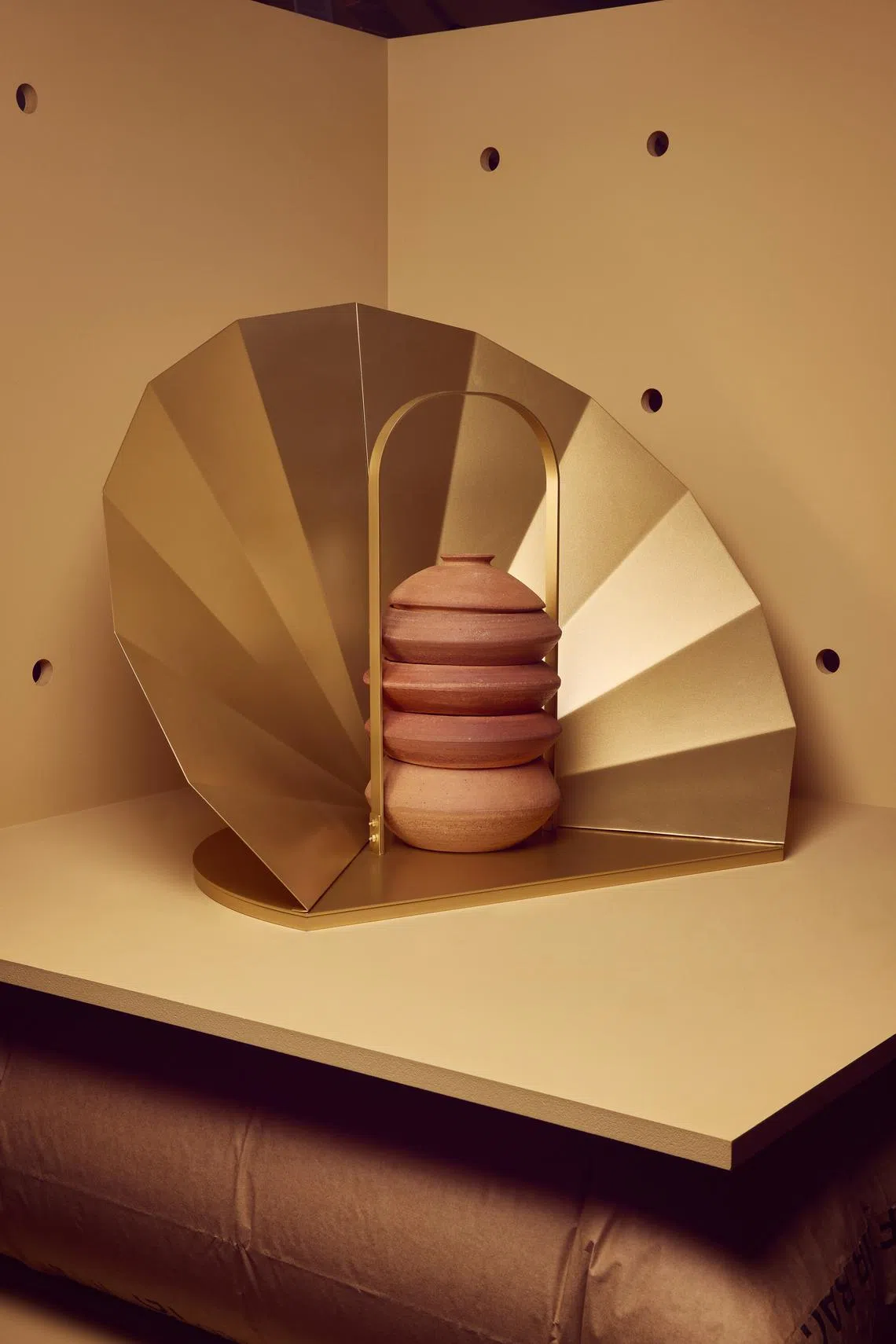

Lee’s Matahari – a tiered solar cooker crafted from terracotta and metal deflectors – is inspired by the vernacular of South-east Asian cookware and evokes both the ancient and the modern.

“I wanted to celebrate Singapore through the lens of long-form food preparation and the labour of love involved in slow cooking, a practice common across many ethnic groups in Asia,” she says of her new work.

At the same time, it highlights Singapore’s potential as one of the most solar-dense cities in the world. “I bridge the nostalgia of kampung cooking with the ever-forward-looking attitude of Singapore’s sustainability initiatives.”

Although she notes that Singapore “has always been intentional in its design, adept at master-planning its next future”, she believes the next age “will demand a lot of resilience from us”, as things change at a pace that feels hard to keep up with.

“I think design can also teach us a lot about adversity, how to invent ourselves out of tight corners and how to take setbacks with grace,” says Lee, who is working on a few projects involving augmented reality, scenography, public art installation and spatialised experiences.

Ng Sze Kiat

The founder of Bewilder, a mycological design studio, works exclusively with fungi, developing products in which elements of surprise and wilderness interplay with containment and control. Ng’s special focus is on ganoderma reishi (or lingzhi), which is also the star of Fungariums In Space, where they are grown – fuss-free – in stainless steel fungariums.

“With our fungariums, not only are you able to grow lingzhi beautifully, you can also harvest the mushrooms and make a medicinal tea to bolster your health and wellness,” says Ng, who grows the fungi like bonsai – sculpting them into various intentional forms for fungal bouquets.

Currently, he is “knee-deep” in research and development, from growing exotic gourmet mushrooms which are supplied to restaurants, to rare medicinal varieties and sustainable mycelium-based designer products.

Sacha Leong

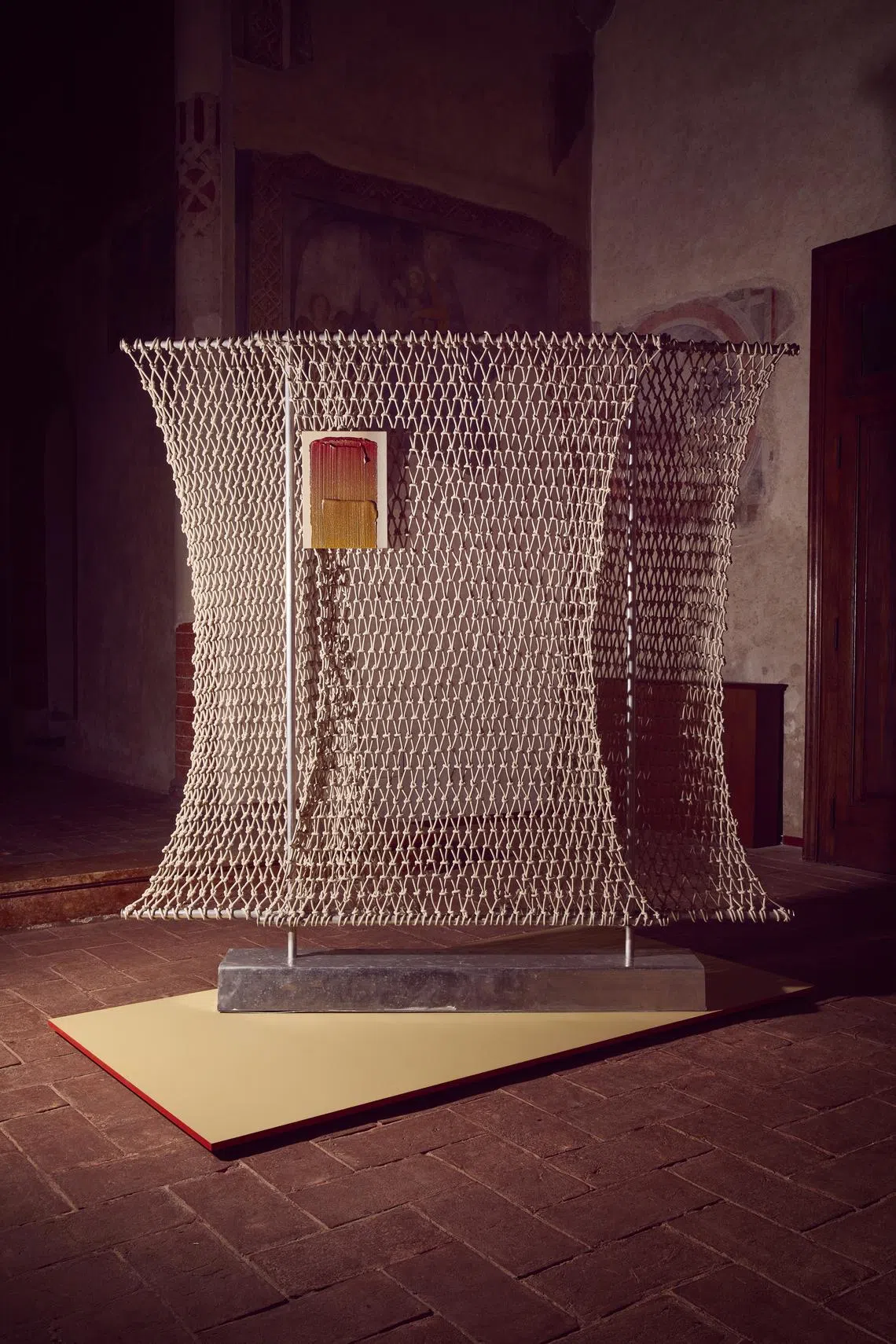

Based in London, the co-founder of Nice Projects works in architecture and interior design and teaches at institutions such as London’s Royal College of Art. His work, Oku Screen, is a response to growing urban populations and overcrowding.

“I wanted to make a handwoven screen that explores the idea of a textured, layered piece of micro architecture that has two uses – it can define a space, but also serve as a surface that can be used for display,” he says.

Inspired by the Japanese concept of oku – a spatial theory revolving around the concept of depth, concealment and the innermost part of a space – the screen combines handmade and computer-based processing methods.

It is produced in partnership with Indonesia-based weaving atelier, BYO Living, using recycled aluminium and simple white rope.

Leong, who is now designing a research lab in Kyoto, a restaurant in Paris and a hospitality and retail space in central London, says a more strategic and inclusive approach to design is needed in Singapore.

“Design has the potential to make an important contribution to Singapore society and help us tackle significant issues around sustainability and quality of life.”

Randy Yeo

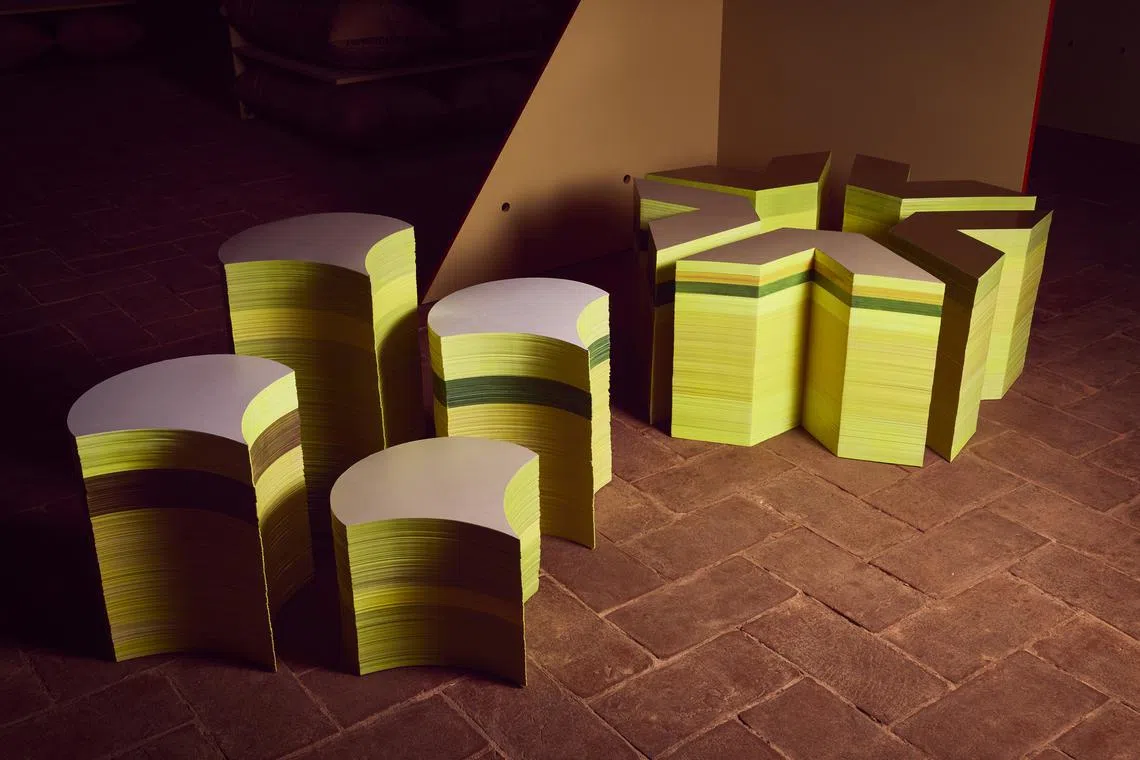

The founder and creative director of branding and creative agency, Practice Theory, was inspired by his long-standing interest in Singapore’s modernist history when he created Modular.

The graphic and architectural expressions of the post-war years led him to make Modular’s two stools, which are based on the logos of Golden Mile Complex and Chai Chee Estate.

“One represents a bold, post-war vision of urban life; the other is one of Singapore’s oldest public housing estates, built on the history of a vegetable market,” says Yeo, who believes design can offer a softer, more human lens in systems- and efficiency-focused Singapore.

Each piece is made from waste paper sourced from printer and paper merchants across the island, bound like a book and finished with lamination to protect it against the elements.

“What I’m also trying to do with the work is to bring light to this part of our history that tends to be overlooked,” he says. “If modernist values like logic, function and rationality are already part of Singapore’s DNA, part of how the country works, then maybe modernism could be the foundation for a visual language we can call our own.”

Future Impact 3: Design Nation will be held at Milan’s Chiesa di San Bernardino alle Monache, in the city’s historic Cinque Vie district, from now till Apr 13.

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.