Singapore Biennale 2025: Big dreams, big detours

Is more always more? Spread across 28 locations, the sprawl of the showcase is both its strength and flaw

[SINGAPORE] The Singapore Biennale has always aspired to be more than an exhibition – it wants to be an atmosphere, a state of mind, a civic experiment in artistic communion.

This year’s edition, titled pure intention, spreads itself across the island like a cloud of possibility, from the hilltop historicity of Fort Canning to the faded charm of Tanglin Halt and the leafy quiet of Wessex Estate. Even the former Raffles Girls’ School (RGS) and old shopping malls on Orchard Road are roped in as exhibition sites.

The biennale website lists a total of 28 locations in five neighbourhoods. In theory, this diffusion is the point: to transform the city into a stage for contemporary art, a kind of urban symphony of creativity and reflection. In practice, though, it sometimes feels like a playlist on shuffle – filled with great tracks, but missing a through line.

Organised by the Singapore Art Museum (SAM) and led by a curatorial quartet of Selene Yap, Hsu Fang-Tze, Ong Puay Khim and Duncan Bass, the Biennale brings together over 100 artists from various countries for a “deep engagement with Singapore’s rapidly changing social and urban environment”, as they jointly state.

A city scored in many keys

But as one travels from one site to another, the city’s “rituals, lived experiences and aspirations” appear less as cohesive music than a series of isolated solos. Each artist plays beautifully in their own key – but together, the orchestra feels like they’re still rehearsing for opening night.

No doubt, there are exquisite solos that justify the journey. Over at Blenheim Court in Wessex Estate, for instance, a three-storey colonial-era building has been transformed into a powerful site of multimedia installations.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

On the ground floor, Jesse Jones’s The White Cave reimagines prehistory as a feminist seance, where the sea becomes an ancient archive of female voices. One floor up, the South Korean collective ikkibawiKrrr’s Seaweed Story honours the haenyeo divers of Jeju Island – ageing women who dive for seaweed and remembrance alike.

Another floor up, architectural duo field-0 traces the hydroelectric power connections between Singapore’s Changi Jewel Rain Vortex and Thailand’s Vajiralongkorn Reservoir, where the construction of a new dam destroyed the homes of indigenous hill tribes.

Besides Wessex Estate, Tanglin Halt is another site of terrific works. At Block 48, Adrian Wong turns a humble shophouse into a film set, splicing fragments of old Hong Kong film culture with his own family history.

At Block 47, Joo Choon Lin shapes everyday materials into an evolving installation that folds, shifts and reconfigures. Meanwhile, at Block 49, Kah Bee Chow reimagines a former Chinese medicine shop as a musical composition, using its leftover fittings – wood shelves, mirrors, wall marks – as notation.

The problem of sprawl

Beyond this, the Biennale becomes harder to follow, with works scattered across shopping malls, Fort Canning Hill, and the former RGS building on Anderson Road, among many other locations. It’s an ambitious expansion, no doubt, but it’s difficult to navigate. Neither the information-light booklet nor the click-heavy website (with no visible search function) offers much help.

At the former RGS on Anderson Road, there are over a dozen works displayed in approximately ten spaces in different buildings. In the Angklung Room, Brandon Tay has a magnificent installation proposing that intuition and the subconscious can shape scientific progress as profoundly as reason. In the Theatre Workshop, excellent films by Riar Rizaldi and Diakron & Emil Ronn Andersen are being screened. The school field is a highlight, with three outstanding outdoor installations curated by Singapore collective Hothouse.

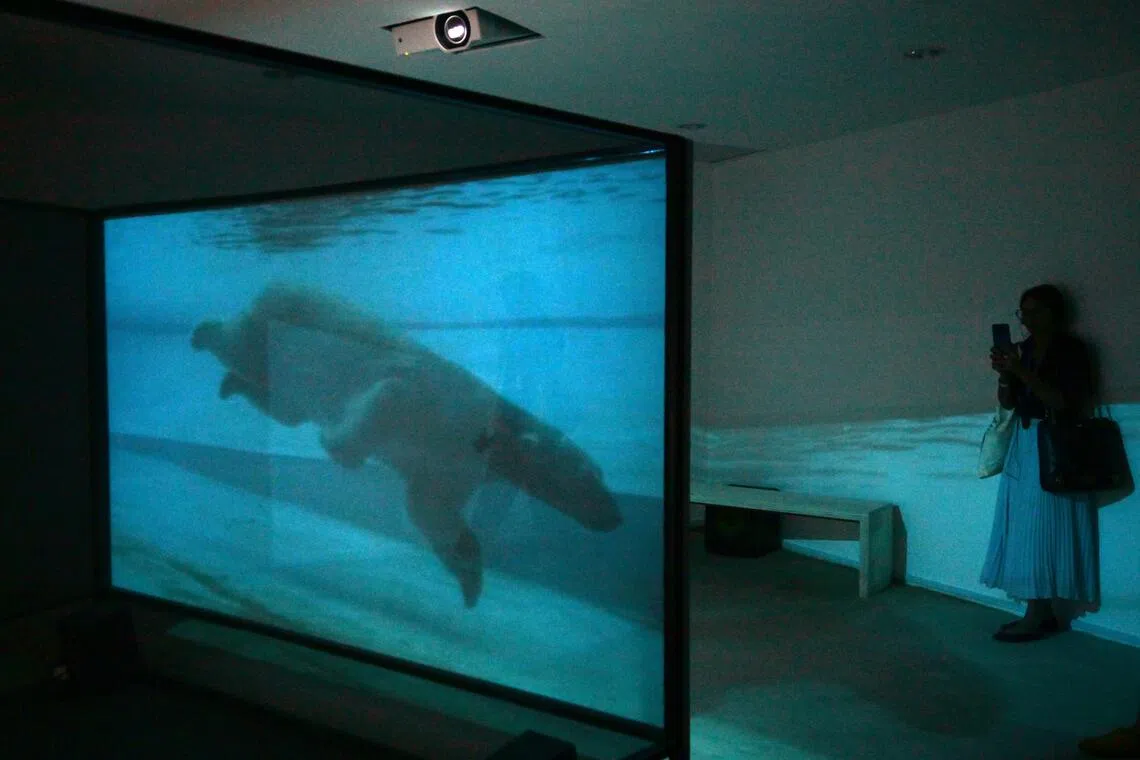

Meanwhile, at Lucky Plaza, Eisa Jocson’s The Filipino Superwoman X H.O.M.E. Karaoke Living Room transforms a shop unit into a karaoke lounge made with and for domestic workers. Nearby, Tan Pin Pin’s video installation On A Clear Day You Can See Forever juxtaposes a one-shot take of a continuous drive along the PIE with footage of Singapore’s first polar bear Inuka pacing in his enclosure, a sharp commentary on how cityfolk and animals in captivity move within designed systems of control.

But there are several other works in other malls too, such as Far East Shopping Mall (where Thai superstar Rirkrit Tiravanija gives away free T-shirts at the basement), Peninsula Plaza (where poems by migrant workers pop up in unexpected places) and The Adelphi (where Maha Maamoun has a photo and video installation in the lobby of Peter Law Chambers).

A glut of good ideas?

By now, the visitor – weary from shuttles and site maps – begins to wonder whether the city really needs art in every corner, or whether a few good locations might suffice.

Fort Canning Hill had works scattered at Fort Canning Centre, Fort Gate, the Lighthouse, the Raffles House Lawn and Oldham Theatre. A couple of these locations have only one work – so if one were too tired to make the trek up the hill, one would miss Ayesha Singh’s rather beautiful Continuous Coexistences (Singapore) at Raffles House Lawn which renders the city skyline as a continuous line sculpture – a line that threads together Singapore’s architectural identities from ancient shrines to modernist landmarks.

The Biennale’s expansion across so many locations can leave you feeling adrift between contexts. The curatorial challenge of wanting to be everywhere at once reflects ambition, yet the sprawl inevitably dilutes the impact.

Even at SAM’s homebase in Tanjong Pagar Distripark, the Biennale feels a bit scattered. One moment you’re studying Lim Mu Hue’s precise modernist woodcuts from the 1960s; the next, you’re looking at Pierre Huyghe’s Offspring, an artificial intelligence-powered swirl of light and smoke. Both are remarkable in and of themselves, but together they feel less like a dialogue than two strong voices speaking past each other.

The burden of pure intention

SAM is one of the country’s most illustrious art institutions, with a track record of mounting exceptional solo and mid-scale shows. In recent years, the solo shows of Heman Chong, Yee I-Lann, Pratchaya Phinthong and Ho Tzu Nyen impressed many with their depth, intelligence, editing and staging.

But faced with the Biennale’s unwieldy scale – over 100 artists, multiple venues, and a sweeping brief – SAM seems to strain under the weight of wanting to include so very much, give every voice its moment, give every district its activation.

Perhaps the Biennale is not meant to be consumed in three days – as this reporter had to, to meet a publishing deadline – but to be experienced slowly through its six-month run. Perhaps its sheer range is, in its own way, the most honest portrait of Singapore: restless, overextended and perpetually in search of its next pure intention.

In the end, pure intention is both an appropriate title and a quiet self-diagnosis. It’s a show full of generosity, sincerity and ambition – but it’s also diffused and unresolved.

For more information, visit singaporebiennale.org

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.