Under Kaws’ moonlit glow, a Singaporean leads Manar Abu Dhabi’s night-time art show

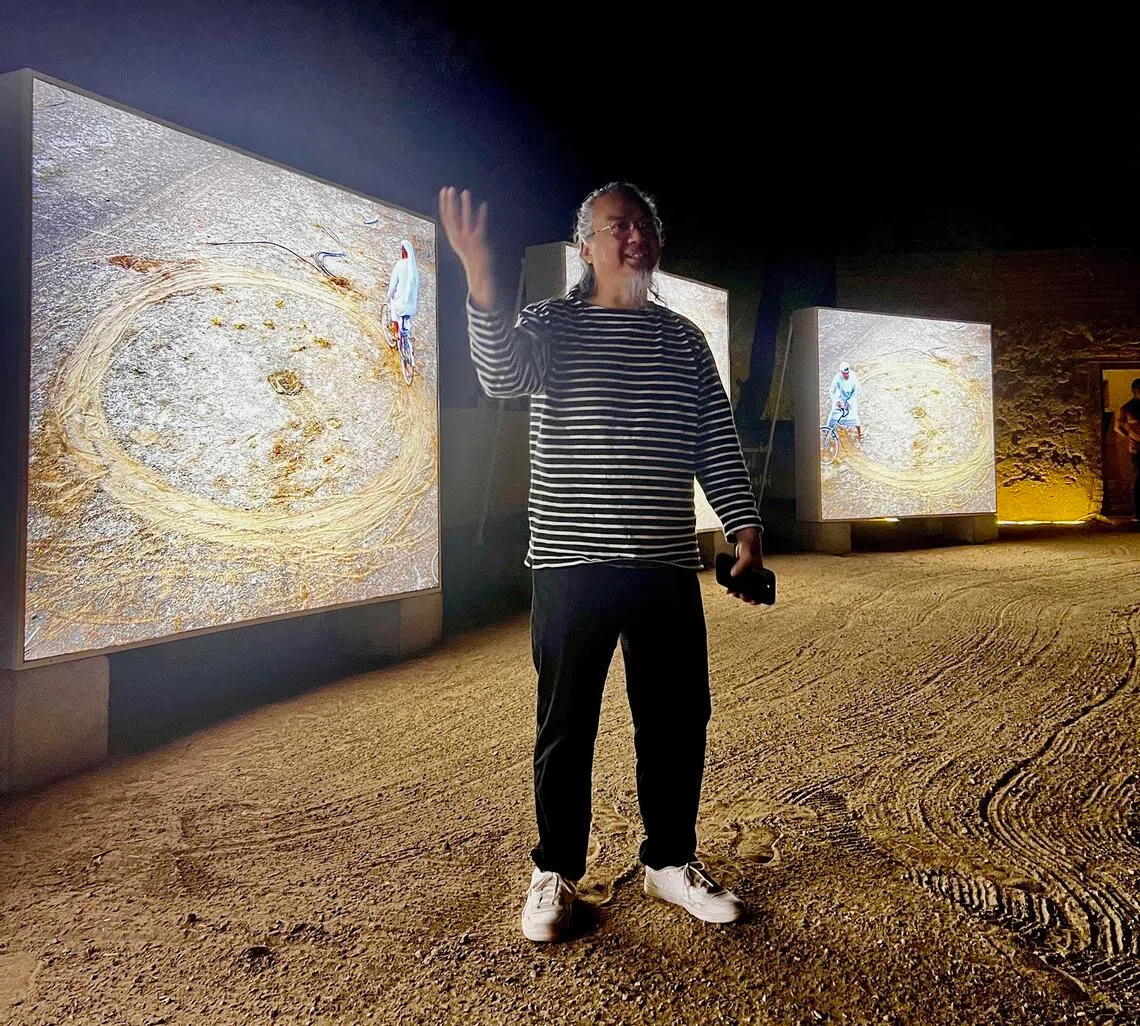

Curator Khai Hori turns mangroves, deserts and historic sites into a cosmic wonderland

[ABU DHABI] A giant grey figure lies glowing by the Abu Dhabi waterfront, its hands cupping a luminous moon as if it has just been plucked from the night sky.

It is unmistakably a Kaws creation – a colossal, reclining Companion “mega-toy” that has, for days, dominated both the skyline and the Instagram feeds of anyone living within a 20-kilometre radius.

And yet, it isn’t even the most surreal sight in Abu Dhabi right now.

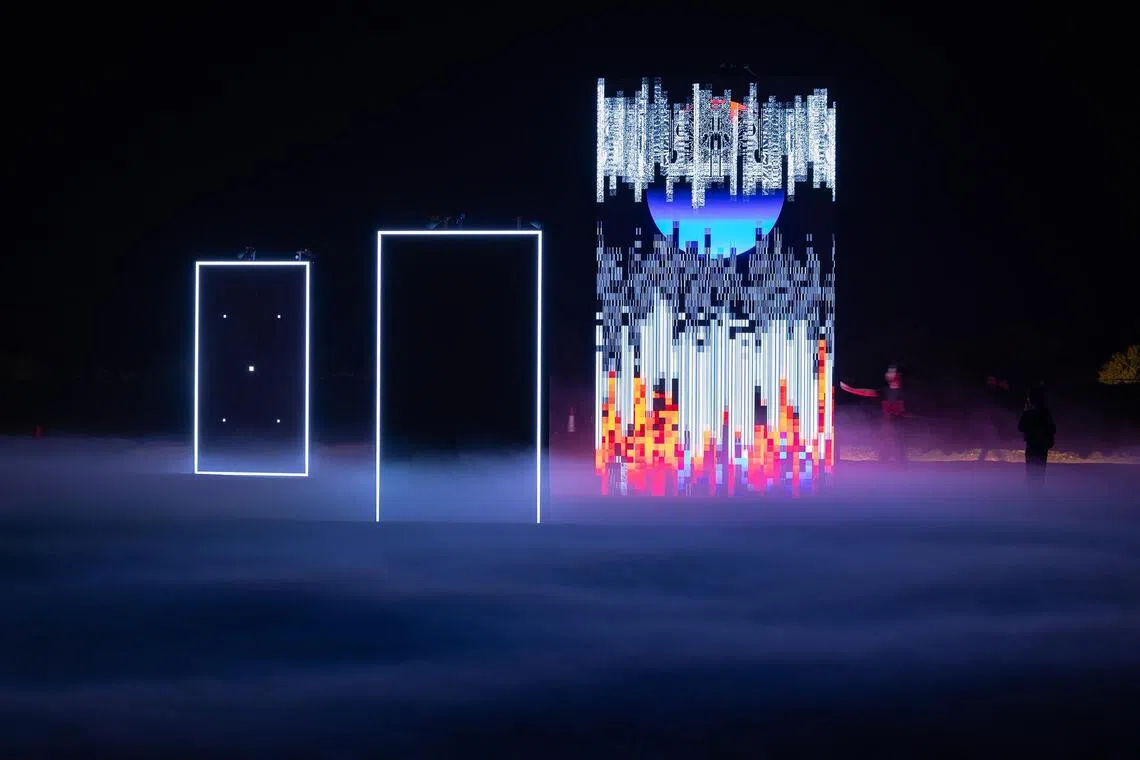

Across the emirate, 22 monumental light artworks have transformed mangroves, forts, markets, islands and desert oases into shimmering, nocturnal dreamscapes. Together, they make up Manar Abu Dhabi – a vast wonderland of light and land art that has, since Nov 15, quietly become one of the region’s most striking cultural statements.

But perhaps the most surprising thing about it, is that it has a Singaporean artistic director at the helm.

Khai Hori, 51, didn’t apply for the job. He wasn’t headhunted by an agency. “They contacted me through Instagram,” he says, laughing. “I thought it was a scam.”

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

But a Zoom call later became a plane ticket, which then became a presentation in front of Abu Dhabi’s Department of Culture and Tourism – and within hours, the appointment was his.

Khai is well-known in South-east Asian art circles. A former senior curator at the Singapore Art Museum, he was invited to be deputy director of artistic programming at Palais de Tokyo in Paris before returning home to co-found art gallery and advisory Chan + Hori Contemporary. He also helmed the Art Galleries Association Singapore as its president from 2018 to 2023.

Yet, after a demanding few years, he had hoped to take things slower – until that Instagram message changed his trajectory entirely.

“I took on the job because I was fascinated with the Gulf’s ancestral relationship with astronomy and navigation – how early Arab societies read light not as spectacle, but as a tool for survival, spirituality and knowledge,” he says.

He cites devices like the kamal and the astrolabe, and age-old practices of reading stars to cross seas and deserts as “inspirations” for the show, which places contemporary light art in dialogue with these histories.

Here, artificial light powered by electricity and code is set against heritage sites, mangroves, fort walls and archaeological grounds.

A city’s glow-up

The gems among the exhibits include Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s Pulse Canopy, which transforms visitors’ heartbeats into long glowing beams that shoot into the night sky, as well as Translation Stream, which projects contemporary Emirati poetry as flowing ribbons of light across buildings and pathways.

Shaikha Al Mazrou’s much-raved-about mangrove installation is a naturally glowing red pool, where seawater and salt crystallisation nurture algae and bacteria that tint the water crimson – creating a quiet, contemplative blend of light and natural process.

Meanwhile, deep in the Al Ain Oasis, Khalid Shafar overlays traditional weaving motifs onto the ground as illuminated red carpet-like patterns, anchoring contemporary public art to historic mud-brick architecture.

Besides them, Dutch studio Drift also impresses, with an interactive dome that generates a unique digital flower for each visitor, as well as a field of illuminated fibre-optic stems that respond to the wind.

Most of the works, including those by Pamela Tan, Iregular and Maitha Hamdan, are located on Jubail Island and in Al Ain’s historic neighbourhoods. And though the sites are sprawling, dozens of buggies are on hand to ferry visitors from one work to another throughout the night.

Wider cultural shifts

The glow of Manar’s installations is only one part of a much bigger picture.

Reem Fadda, a well-known art historian and director of culture programming at the Department of Culture and Tourism, describes Manar as part of a decades-long master plan involving government agencies, real-estate developers and urban planners.

“We’re shaping the language of the city,” she says. “Public art isn’t decoration. It’s civic infrastructure – a guarantee that art is not elitist, that it belongs to everyone.”

The public has responded strongly. Last year’s Public Art Abu Dhabi Biennial drew 2.8 million visitors, while Manar’s inaugural edition in 2023 attracted 770,000. Each edition introduces works that may eventually become permanent landmarks in the city.

Across the emirate, a wider cultural shift is unfolding. The Louvre Abu Dhabi made global headlines when it opened in 2017. The upcoming Guggenheim Abu Dhabi and Natural History Museum will soon join the Louvre in a rapidly expanding Saadiyat cultural district already home to teamLab’s museum Phenomena and the Zayed National Museum.

For Fadda, this momentum is not sudden growth but overdue recognition. “Abu Dhabi has been building cultural infrastructure for 20 years,” she says.

As a scholar of Arab modernism, she often highlights the region’s rich artistic past – from early avant-garde movements to Arab artists once in close dialogue with Europe – histories she says were long overshadowed by Western narratives.

“There’s been amnesia – either deliberate or accidental – of Arab contributions,” she says. “But the histories were always here. And the world is only now starting to notice.”

Nomad’s splashy debut

Meanwhile, the cultural calendar is filling up. This week alone features two major art and design fairs, Nomad Abu Dhabi and Abu Dhabi Art.

The acclaimed Nomad – with editions in Monaco, St Moritz and Capri – opens in Abu Dhabi for the first time, bringing collectible design and art pieces to the iconic, disused Zayed International Airport.

Among its participants is Parisian gallery Galerie BSL, founded by Beatrice Saint-Laurent, whose Middle Eastern clientele already accounts for some 12 per cent of her business – a figure she sees rising. “Abu Dhabi feels ready for its next evolution,” she says.

For Abu Dhabi, she brought two collections she thought would resonate with the audience: Pierre-Marie Rader’s Sea Anemone series, inspired by coral formations, and Nada Debs’ Gandhara Carapace works, crafted in Pakistan from semi-precious stones and marble.

“Debs is one of the most important female designers from the Middle East,” Saint-Laurent notes. “And the stone inlay – people here recognise it immediately. You see similar patterns in mosques, in this airport, in the region’s architecture.”

A growing, intelligent audience

Meanwhile, at Saadiyat cultural district, Abu Dhabi Art has returned for its 17th edition with 142 galleries from 34 countries – an astonishing 40 per cent jump in participation from last year. Prominent international galleries include Pace, Almine Rech and Waddington Custot.

Among the returning galleries is Seoul-based Barakat Contemporary, taking part for the fourth time. Known for its unusually global roster, the gallery has long focused on cross-cultural dialogue rather than market expansion.

“We’re a South Korean gallery, but one of the very few in Korea to represent such a diverse roster – Middle Eastern, African, European, South-east Asian,” says director Dain Oh. “For us, that diversity reflects the most urgent issues of our times.”

Abu Dhabi, Oh says, has become “a really exciting hub”, especially as new museums and institutions position the city as a bridge between the Global South and the wider art world.

“We always try to bring works with an urgent purpose – political, technological or materially innovative,” she adds. “And the audience here is receptive. It’s an intelligent audience.”

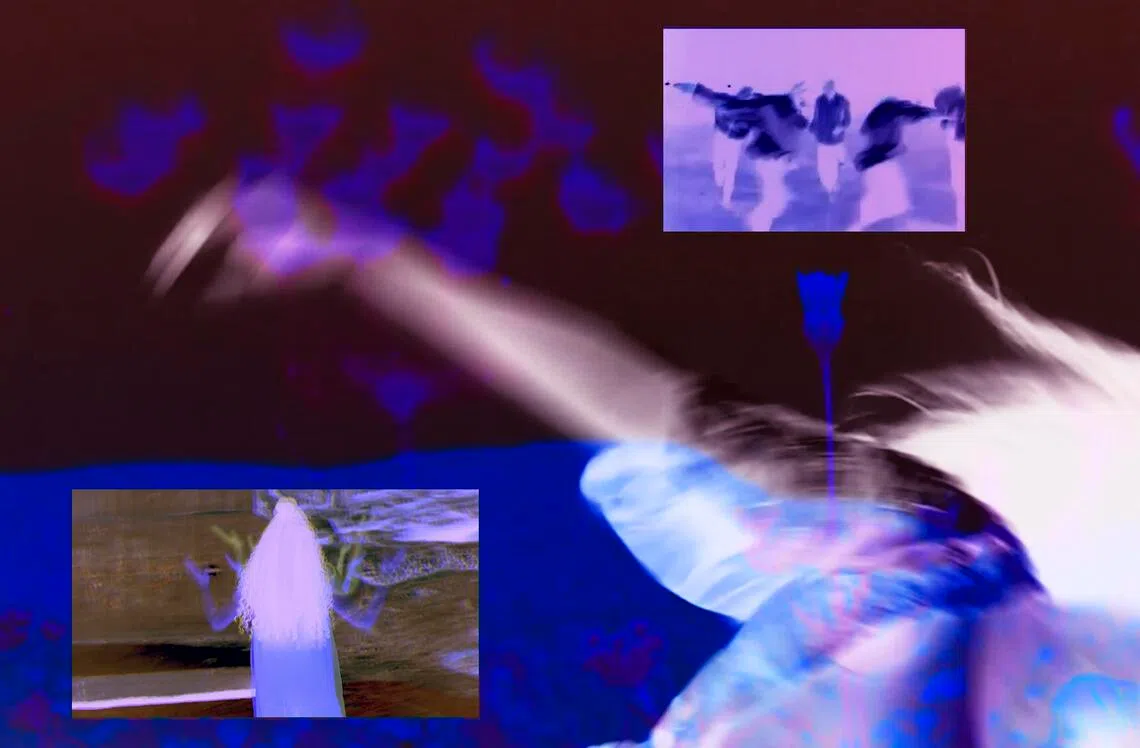

One of Barakat’s standout works is a piece by Palestinian-descent artists Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme, who splice sights and sounds from conflict regions into “desktop performances” – multi-screen collages assembled live on a computer interface.

Taken together – the globalism of Abu Dhabi Art, the design-world glamour of Nomad, the glow of Manar, the expansion of Saadiyat cultural district – the city’s cultural ambitions appear boundless for now.

For Khai, the key revelation has been the city’s appetite for “big ideas”. “There’s a generosity here, a willingness to try anything,” he says.

And while Abu Dhabi is increasingly defined by its mega-museums and sweeping development plans, he argues that the city’s cultural impact ultimately hinges on something more granular.

“A lot of things here look spectacular from far away. But when you experience them in person, they become surprisingly personal and intimate.”

Manar Abu Dhabi runs till Jan 4, 2026. Nomad Abu Dhabi and Abu Dhabi Art run till Nov 22 and Nov 23, respectively.

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.