Tony Leung: The art of stillness

In an age of loud heroes, he commands the frame differently

TONY LEUNG CHIU-WAI IS FACING the camera, following instructions. The photographer asks him to look thoughtful. Leung complies. His expression withdraws and something gathers in his eyes, as if a private memory has surfaced from somewhere deep. There is hurt there. It lingers and deepens.

The photographer issues a new instruction: Look towards the door. Imagine you are seeing someone you haven’t seen for some time.

Leung’s face shifts again. The distance dissolves. His eyes warm. His posture softens. It is as if he recognises someone he loves – and still does. This time, what gathers in his eyes appears to be joy.

For the next 20 minutes, he moves, on instruction, through mood after mood. There is no Wong Kar-wai, no Christopher Doyle, no film crew here. And yet Leung seems to compress entire scenes, even lifetimes, into a handful of gestures. It is emotional and physical control exercised with absolute precision.

“I like Singapore,” he says with a broad smile, once the shoot wraps at Marina Bay Sands’ Cantonese restaurant Jin Ting Wan. “It’s like a good friend of mine, for a long time. I miss the food here very much. The chicken rice and laksa are my favourites.”

The Hong Kong actor was in town to present his new film Silent Friend at the recent Singapore International Film Festival, but the visit feels less like an arrival than a return.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

“In the 1980s, I came to Singapore very often,” he recalls. “I came to sing on stage and promote my TVB series. So it’s a very familiar city to me.”

And though he has never shot a feature here, he says he would welcome the chance. “I really wouldn’t mind. I love shooting in different countries.”

Against the grain

The composure he carries today was not innate – it was earned. In the 1980s, even after achieving television stardom through series such as Police Cadet and The Duke of Mount Deer, he was still racked by doubt.

“I felt my acting wasn’t good enough,” he recalls quietly. “I would go to the office of Lam Lai Jan and cry in front of her.” Lam was the first producer who recognised his potential and cast him as the host on the children’s television programme 430 Space Shuttle.

Fortunately for the film world, that self-doubt did not harden into paralysis. By the 1990s, Leung had stepped away from television towards something far more elusive: a film career shaped less by strategy and calculation than by instinct and curiosity.

“I never plan,” he says. “I just let things happen. If something comes up and I find it interesting, I take it.”

At the time, Hong Kong cinema was operating at industrial speed, producing hundreds of films a year fuelled by swagger and spectacle. The box office was dominated by John Woo’s action films, Ringo Lam’s gritty urban dramas, and Tsui Hark’s martial arts sagas, among others.

Stars such as Chow Yun-fat, Jackie Chan and Jet Li projected masculinity at full volume – heroic, physical, built for blockbusters.

Leung, however, was moving differently. He was learning how little he sometimes needed to do for the camera. Though perfectly capable in commercial films, he was beginning to specialise in restraint.

A different masculinity

In Days of Being Wild (1990), his first collaboration with Wong Kar-wai, he appears briefly only in the final moments – combing his hair, folding a pocket square, slipping into a coat, preparing for a life the audience will never see.

What the world glimpsed was an actor capable of suggesting entire histories in silence.

But Leung, characteristically, is quick to deflect credit. “Good directors like Wong use the same formula to help actors get into character,” he says. “They give you materials beforehand – books, paintings, music. They really know how to draw you into your character.”

What followed was a body of work that came to define a new masculine vocabulary in Chinese cinema – one grounded not in macho assertion, but in withholding.

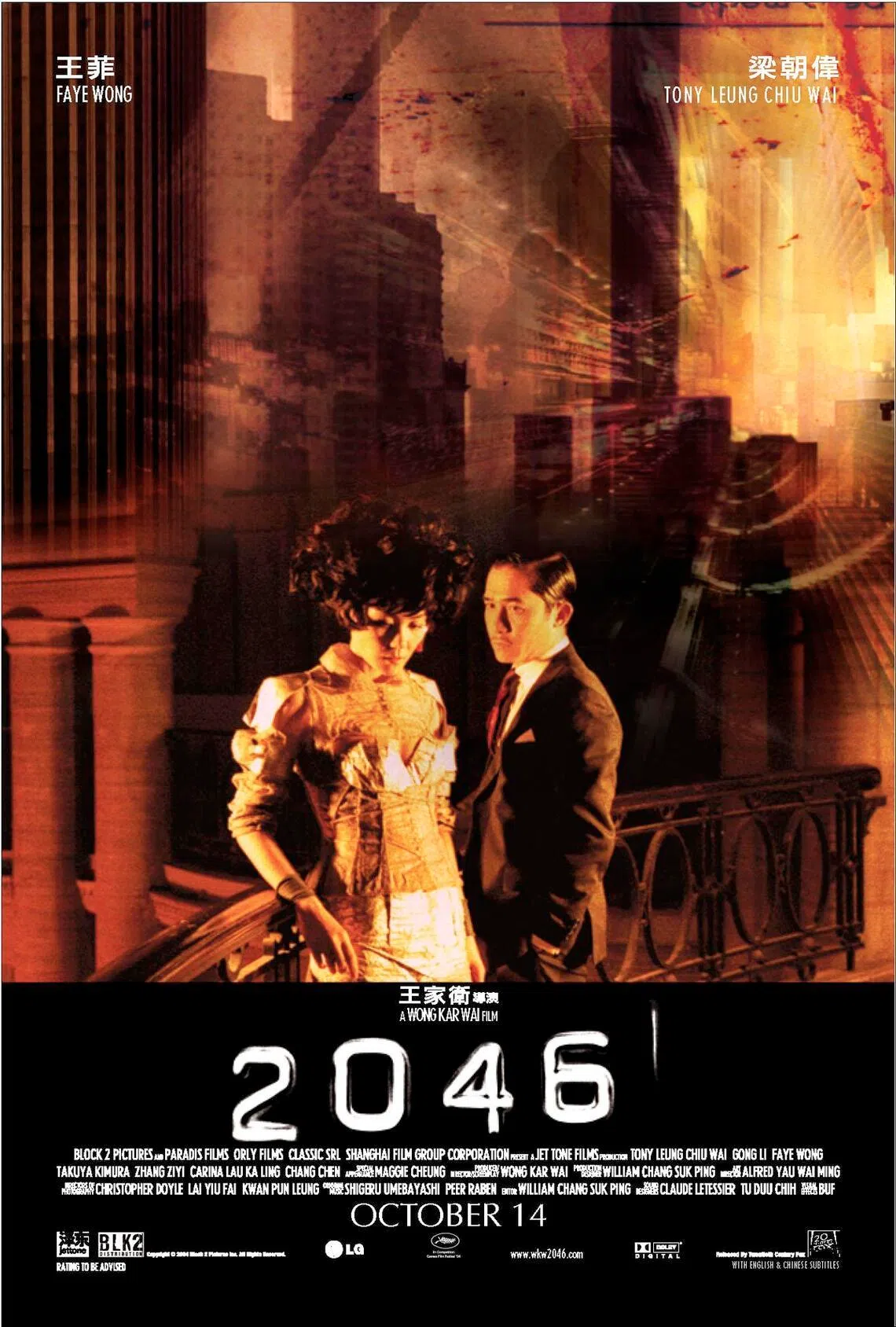

In Chungking Express (1994), Leung’s lovesick policeman moves through neon-lit Hong Kong in a state of distracted reverie – talking to himself, managing heartbreak with gentle self-mockery – his private ache observed only by Faye Wong.

In Ashes of Time (1994), he plays a swordsman haunted by hesitation and regret for the choices he made for a woman he loved. In Happy Together (1997), he clings to the last threads of a volatile relationship with a man portrayed by Leslie Cheung.

These performances became an international calling card – not only for Wong Kar-wai, but for an actor whose sadness felt curiously universal. Leung’s men were not heroes in the classical sense. They were figures defined by vulnerability, longing and hesitation.

Leung is careful, however, not to frame his evolution as the product of his work with Wong alone.

“I’ve collaborated with many directors,” he says, citing Lee Ang (Lust, Caution, 2007), Hou Hsiao-hsien (A City of Sadness, 1989; Flowers of Shanghai, 1998), Tran Anh Hung (Cyclo, 1995), Andrew Lau and Alan Mak (Infernal Affairs, 2002), Destin Daniel Cretton (Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings, 2021), and Ildiko Enyedi (Silent Friend, 2025).

“Every director I’ve worked with plays a very important role in my acting career,” he says. “I wouldn’t (have) become who I am without any of them. Whether it’s a good director or a bad director, I learn something from the process, from the mistakes and successes. Every director is important to me.”

In fact, authorship, as Leung understands it, extends well beyond the director alone. “In Wong’s films, for instance, the shooting set is always good – always good,” he says emphatically. “William Chang does the art direction, from production design to costumes, and he is very talented.”

The art of withholding

By the late 1990s, Leung had become something rare: a leading man whose power lay in his capacity to withhold. Directors trusted his face to do the work of dialogue. Audiences learnt to read the smallest shifts in his expression. He was not performing emotion so much as permitting it to surface – sometimes reluctantly, sometimes all at once.

By 2000, when he starred in In the Mood for Love – often cited as one of the greatest films of all time – the role felt like a culmination.

As a quietly betrayed husband drawn to his neighbour (the luminous Maggie Cheung), Leung distilled a decade of restraint into something exquisitely precise: desire expressed through posture, longing contained in a glance, a performance built almost entirely on what is not said between them.

When the film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, Leung was awarded Best Actor – recognition not for grand transformation or dramatic excess, but for a performance assembled from absence and suggestion.

Leung had learnt how to let silence speak, how to make stillness legible. What once sent him crying into a producer’s office became his greatest asset – a heightened sensitivity to emotions others scarcely notice.

Yet, that same sensitivity has a cost. Decades of playing quiet, repressed men – absorbing their restraint, their unspoken ache – have taken their toll.

“These days, I have a lot of scripts in my house, but I don’t want to read any of them,” he says. “I’m not in the mood to make movies. Sometimes I take a really long break after one film – sometimes three years – just doing nothing, just being myself.”

At 63, his relationship to time itself has shifted. “I’ve changed a lot,” he reflects. “I’ve learnt to appreciate this moment I’m in – instead of always looking back at the past or looking forward to the future, afraid of losing something.”

He pauses, then adds, more quietly: “Not so many people know how to appreciate the moment – to be appreciative whether it’s good or bad, whether it’s a rainy day or a sunny day. To be grateful for what they have now.”

A question of faith

What draws Leung back into motion, he says, is not the promise of a role – but the presence of the right collaborator.

“First of all, the script is not the most important thing to me,” he says. “I think the director is more important, because he or she is the one telling the story. When you put a very good script in the wrong hands, it can’t be a good movie. So I’m not working with the script – I’m working with the person.”

Before committing to any project, he insists on a conversation – sometimes a formal meeting, sometimes a Zoom call. He wants to sense the director’s temperament, their seriousness, their way of seeing the world. Trust, for him, is not ideological; it is intuitive.

Silent Friend came together this way. “Ildiko (the director) is very intellectual, but also very nice and humble. She knows exactly what she wants to do. That’s why I wanted to work with her – to help her finish this project.”

The film marks Leung’s first foray into European arthouse cinema. He plays a neuroscientist who, during the Covid-19 pandemic, begins to wonder whether his methods for studying early human cognition might also reveal something of the inner workings of plants. It is another inward character – one governed as much by curiosity and stillness as by scientific inquiry.

As part of his preparation, Leung read the philosophical book Ways of Being by James Bridle, which considers intelligence beyond the human – plants, systems, machines. The book left him less anxious than reflective.

Asked whether artificial intelligence troubles him as an actor, he shrugs. “I don’t know how I feel about AI,” he says. “Maybe it will take over our jobs – but it’s okay.”

That acceptance, he admits, has come with being 63. “Being older makes me more easy-going,” he says. “Before, I was pretty shy. I seldom talked that much. But because of life experience, because of getting mature… I’m more accepting.”

Receding, not disappearing

One could argue that this acceptance has always been there, quietly embedded in the roles Leung gravitates towards – from Mr Chow in In the Mood for Love, who falls for his neighbour but chooses not to act on it, to Ip Man in The Grandmaster (2013), a man for whom discipline and restraint ultimately eclipse his longing for Gong Ruo Mei (played by Zhang Ziyi).

Off-screen, that same instinct has shaped his private life. Married since 2008 to Carina Lau – a cinematic force in her own right – Leung has spoken of a partnership defined less by noise than by quiet continuity.

Asked what his many romance films have taught him about love itself, he thinks carefully before deciding not to draw a conclusion. “I don’t know,” he says, after a long pause. “Movies are more dramatic than real life. That’s it.”

That same reluctance to extract meaning from his films now shapes how he thinks about his career. While other 63-year-old actors, such as Tom Cruise and Michelle Yeoh, continue to move briskly from one big-budget production to the next, Leung has chosen discretion over momentum, spacing his work with long intervals of absence.

“I enjoy being alone,” he says. “You feel very, very peaceful. And you can really think about what you want to do next – what is your value of life now?”

For cinephiles, that does not mean disappearance. Leung will remain present – not as a star in constant circulation, but as a figure who lingers: on screen, in memory, in half-lit scenes built from glances and silences.

It is not a retreat so much as a position he has learnt to inhabit. “Nothing is permanent,” he says. “Things go up, they come down, and they go up again. Who knows?”

Photography: Darren Gabriel Leow Fashion direction: CK Grooming: Alison Tay, using Chanel Beauty Location: Jin Ting Wan at Marina Bay Sands

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.