Lovingly restored: Take a peek into the wartime shophouse where Lee Kuan Yew hid

The original three-storey structure is one of seven built in 1925

IT IS 6 pm on a Monday evening. On Maude Road, an unremarkable street in the old district of Jalan Besar, the sound of warbling emanates from one of its several nightclubs.

Gentrification may have changed the identity of some nostalgic enclaves, but it hasn’t yet arrived at this road, which is lined with shophouses on one side and newer buildings on the other. Just as well, because a long-forgotten shophouse has slowly and quietly been undergoing restoration to return to its rightful place as a property of historical significance.

This almost stealth-mode reconstruction seems to befit 75 Maude Road. In the midst of World War II, it was where Singapore’s founding prime minister Lee Kuan Yew hid to escape a mass screening at the nearby Jalan Besar Stadium. In his memoir, Lee said that had he not found refuge in what was a lodging house for rickshaw pullers during the Japanese Occupation in February 1942, he would most certainly have been taken to a beach near Changi Prison and shot to death.

Today, that shophouse – which was previously occupied by an electrical business, cleaning company and possibly even a nightclub before being left vacant and derelict for years – has been lovingly rehabilitated.

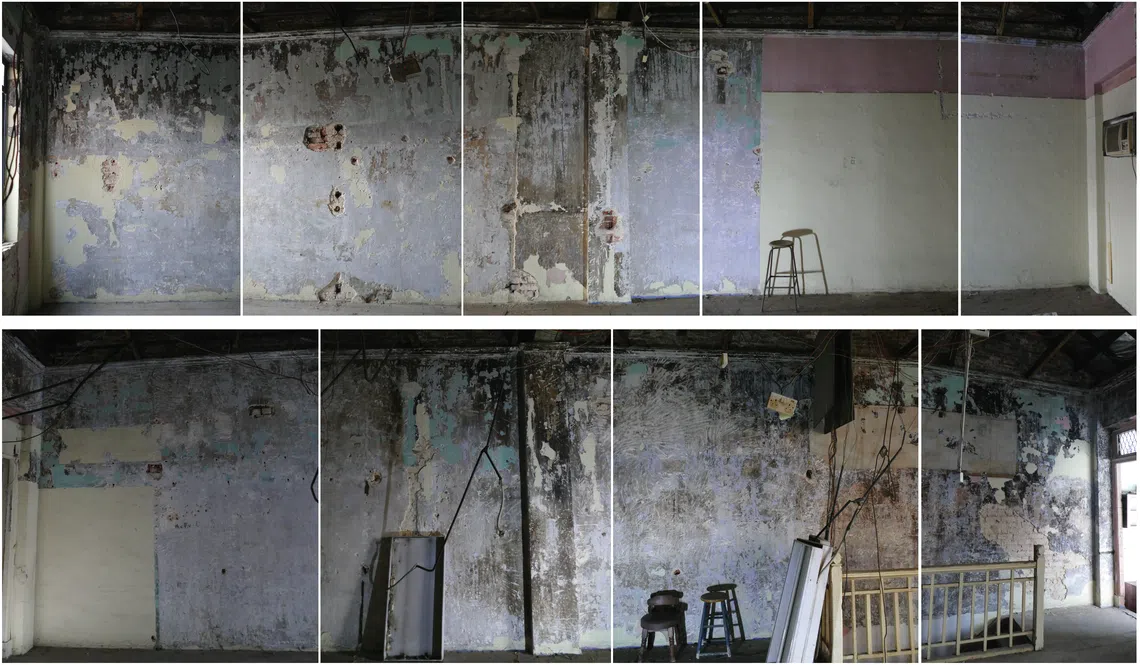

But while it has taken S$3 million and about three years for 75 Maude Road to clean off years of grime and neglect, don’t expect a stunning, Instagram-friendly makeover. Instead, what you’ll see are elements of its past as a humble home for the working class, now juxtaposed against the newer, modernised portions of the property.

A working-class neighbourhood

Ho Weng Hin, architectural conservator and co-founder of Studio Lapis, was hired to lead the restoration work. “This was quite an interesting project because the owner really wanted to let the history of the building come alive,” says Ho. Zain Fancy, founder and managing director of property investment firm, Clifton Partners, bought the property in 2021.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

Named after Frederick Stanley Maude (1864-1917), a British army commander, Maude Road was an enclave for Hock Chia immigrants from China in the early 1900s. Jalan Besar itself was a place of congregation for masses of rickshaw pullers who lived, worked and socialised in the area.

“In the past, probably 50 to 60 people were packed inside this building, sharing maybe two or three bathrooms and cooking in the yard,” notes Ho. “So it was quite a difficult situation.”

The original three-storey shophouse was one of seven built in 1925, and meant as a boarding house with rooms for rental on the upper storeys. “We found that it was developed as a residence because its original configuration had a classical door flanked by timber casement windows,” says Ho.

A dilapidated property

The area where 75 Maude Road stands was not gazetted for conservation until Oct 25, 1991.

Meanwhile, in the post-war years, the building was converted to commercial use, with its facade changed to a single large shopfront opening with a collapsible gate. The staircase that was originally accessed from the interior and located in the centre of the property was moved to the side of the building, with its own access door.

On the second floor, the French window flanked by two windows on the parapet walls had been removed and replaced by characterless sliding glass windows. One of the three intricate timber arch vents above the windows was gone, but the frieze above them featuring festoons and floral motifs were still present.

The third storey held the most intriguing revelations about life all those decades ago. Its recessed balcony, with its moulded concrete railing supported by precast concrete bottle balustrades, is an interesting configuration. It reflects aspirations for a better lifestyle, where people have the leisure of hanging out on the balcony, observes Ho.

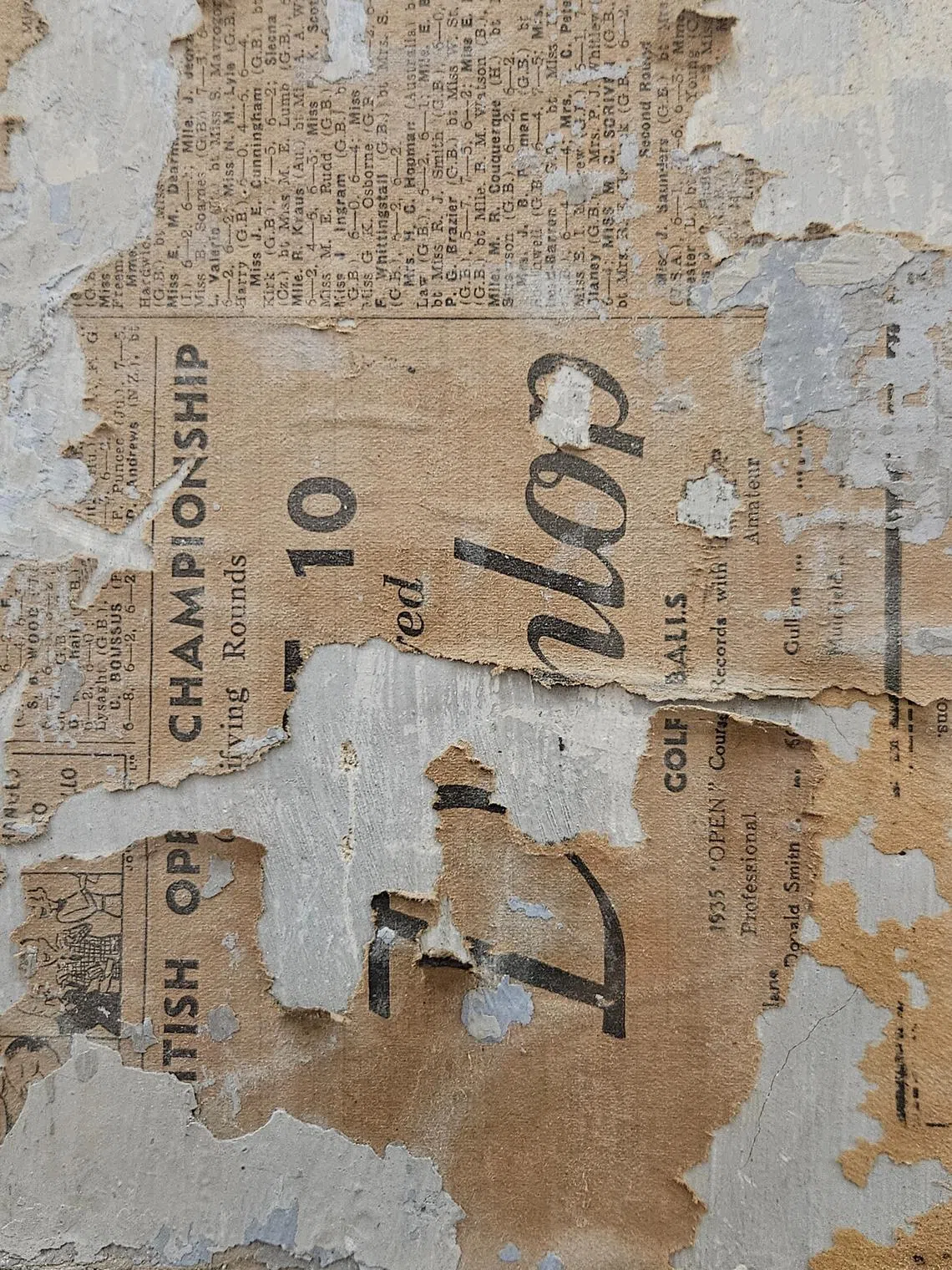

Inside, was a fascinating discovery – a stretch of wall plastered with newspapers, from as long ago as the 1930s. Considering that the labourers were illiterate, this was all rather strange, says Ho.

“We don’t know why they did that. But some think that people used the newspapers to cool down the walls, like a form of humidity control. This could be a sign of how people try to adapt their environment for comfort.”

Overall, the property had suffered plenty of damage and deterioration, mostly due to moisture. This had led to the disintegration of the paint, plaster and brick masonry, with rotten and broken timber doors and windows, as well as crumbling walls revealing construction materials such as rusted rebars.

A labour of love

With the retention and reinstatement of defining architectural features as a priority, Ho worked with Forum Architects and Ming Construction to restore the property. The original entrance configuration of a central door flanked by two casement windows was reinstalled. Vertical bars were also fixed in the windows – mimicking the past, when they ensured security while the timber windows were open for ventilation.

Timber fretwork panels were handcrafted in Indonesia to replicate those that used to sit above the doors and windows. During construction, red cement tiles were found under a thick layer of cement screed on the ground floor near the entrance. The patterned ones were painstakingly removed to avoid damage during construction before being carefully replaced later.

Meanwhile, the shophouse’s old metal collapsible gates were kept and installed throughout the property, including as a decorative feature by a staircase at the back. Pairs of breeze blocks recovered from the demolished rear toilet and kitchen area now take pride of place as wall ornaments on every floor. Cornices were retained and the timber floorboards and joists were repaired, sanded and varnished, allowing the wood grains and texture to shine.

At the request of the owner, who wanted the shophouse to show traces of its previous occupants, Ho also explored a slightly different approach to conservation – by selectively keeping some of the property’s “distressed historic fabric”.

“That means not everything is spick and span and fully done, so the patina of history is retained,” he explains.

Hence, an old fan that no longer works still hangs from the ceiling, like a silent witness of the eras gone by. Newspapers on the third-storey walls were kept – and protected behind glass panels. The different layers of paint and plaster, nail holes and portions of exposed brick have also been retained as windows into the shophouse occupants’ past.

“The most challenging part of the work (was) determining the right balance between full and half-way repairs,” says Ho. “What is the right balance to achieve? After all, it is going to be rented out and some tenants may not take to the distressed look.”

A new future

It shouldn’t be long before we find out if indeed businesses will take to the shophouse’s aesthetics, as the 4,790 square foot unit will soon be put up for rent. The ground and second floors are suitable for a food and beverage operator, while the upper floors – including a fourth-floor space at the back – could be used for an office or fitness studio.

Work is currently underway to create a marker explaining the history of the property, to be installed in the shophouse foyer and/or back lane for public viewing.

Today, alongside Chinese eateries, 75 Maude Road’s neighbours include nightclubs and bars, a nursing association, clan association, hardware shops, offices and residences.

And as night falls, bar girls hang around a few doors away, eyes peeled for potential customers. It’s a pity that they are probably oblivious of the area’s rich history.

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.