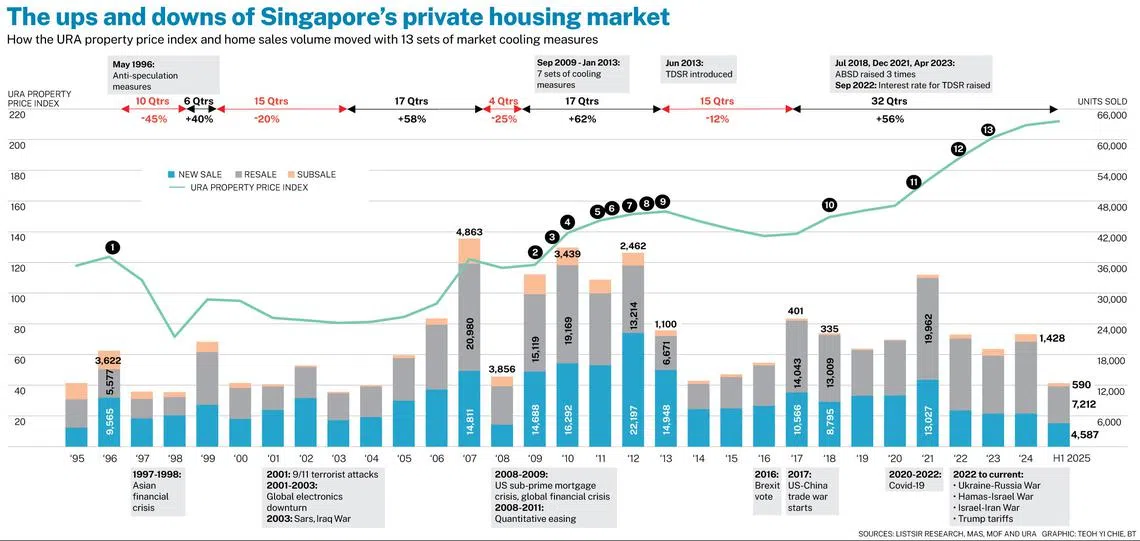

SG60: From surge to stability – a timeline of Singapore’s property market cooling measures, 1995 to 2025

OVER the last three decades, the Singapore government rolled out more than 10 rounds of measures to cool the property market, each time aiming to tame rapidly rising housing prices and calm fevered buying. Various levers were pushed and pulled, making both supply and demand-side adjustments.

The Business Times tracks the interventions between 1995 and 2025 for a closer look at what moved the government to act, and how the market moved in response.

1995-1999

Spurred by strong growth as the economy emerged from recession in 1985, Singapore’s residential property prices spiked sharply in the early 1990s. Home prices surged 36 per cent in 1993 and shot up another 42 per cent in 1994.

In 1995, prices were still levelling up and gained 10 per cent. Prices of non-landed properties in particular – apartments and condominiums – climbed 17 per cent in the year. Condo prices rose another 5 per cent in the first quarter of 1996.

Early in May 1996, then minister for national development Lim Hng Kiang flagged that the authorities were looking into speculative activity, warning that prices had risen too quickly.

On May 15, the government announced measures to “cool the temperature, stabilise the market, and prevent prices from overshooting”.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

Targeting gains from flipping properties and foreigners’ buying, the market curbs switched on would pave the way for many more similar interventions in the decades to come.

Home prices had run up in the early 1990s for several reasons: robust economic growth; high wages and high savings; very low interest rates and readily available financing; more people upgrading from public to private housing as Housing & Development Board (HDB) flat values rose; a strong sense of confidence in the market; and a rise in foreign buying interest, with Singapore increasingly seen as a safe haven.

In themselves, such dynamics were not problematic, the government said.

SEE ALSO

But if cheap mortgages led people to overstretch, the risk of default, foreclosure and then depressed property prices would rise. Over-exposure to property loans would threaten the soundness of the whole financial system.

Some of the indicators flagged were:

- Housing loans rose 22 per cent per year over the last five years;

- Loans to buy property for investment increased from 19 per cent to 22 per cent in one year;

- Fifty-five per cent of housing loans had more than 80 per cent financing;

- Property-related debt jumped from 56 per cent in 1992 to 68 per cent in 1995; and

- Loans to foreigners buying residential properties totalled S$1.2 billion in 1995.

“While the rise in prices thus far largely reflects fundamental factors, the present speculative frenzy risks pushing prices beyond sustainable levels,” said then deputy prime minister Lee Hsien Loong, leading a press conference also attended by Lim and then finance minister Richard Hu.

“We should check the overheating of the market before it develops into a property bubble.”

May 1996

- Gains from selling properties within three years of purchase taxed as income

- Seller’s stamp duty (SSD) introduced on residential properties sold within three years of purchase

- 80 per cent loan-to-value (LTV) limit for all housing loans

- Foreigners barred from Singapore-dollar housing loans

- Permanent residents (PRs) limited to one Singapore-dollar loan each, to buy a residential property for owner-occupation only

At the same time, supply via the state’s government land sales (GLS) programme expanded. From 6,000 housing units in 1996, land sales were upped to provide for 7,000 and 8,000 units in 1997.

The crackdown sent property stocks tumbling. The Real Estate Developers’ Association of Singapore (Redas) immediately appealed for revisions, arguing that unsold stock piling up would flood into a glut.

As the market digested the shock news, luxury condo Ardmore Park was the talk of the town when it was marketed that June at about S$1,800 per square foot. Prices started at S$4.65 million and went up to S$14 million for 8,740 sq ft penthouses.

About half of the 93 units released during a soft launch were sold to VIP buyers from Hong Kong and Indonesia, described by developer Marco Polo Development as the “who’s who” of the region.

Queues formed for the project’s public launch. Punters were asking as much as S$60,000 apiece for their spots in the line.

At Redas’ year-end dinner in 1996, then DPM Lee had this message for developers: “Do not expect that if the market turns, we will cancel our plans. Assume that we will still be there and better make your calculations.”

Hu echoed that sentiment, saying in February 1997: “Prices have softened 10 to 15 per cent from the top end and we are quite comfortable with that.”

Prices continued to slide. Redas continued to lobby for action, saying the property market was “sickly”.

Sales volume shrank by almost half, from just under 19,000 units sold in 1996 to about 10,000 units in 1997.

In November 1997, with South-east Asian markets reeling from the Asian currency crisis, the government made a “controlled adjustment” to “avoid aggravating the excess supply and pessimistic sentiment in the property market”.

Explaining the need for action, Lee said: “In the last few months South-east Asia has seen considerable financial instability. This has shaken confidence and dampened investor sentiment throughout the region. This major new development has affected the Singapore property market.”

He noted that the private and HDB property markets are “interlinked” and that lower private home prices had already caused prices of HDB executive and five-room flats to soften.

“Exaggerated swings in property values will affect the wealth of the majority of Singaporeans who own private and HDB homes.”

The government would defer about one-third of the year’s GLS supply and postpone the next year’s supply; extend completion timelines; and suspend the 3 per cent SSD slapped on short-term sellers. But there was no let-up on loans. The government “will not stimulate demand for properties by relaxing credit”, said Lee.

In June 1998, the government took further steps. It suspended GLS for the rest of the year and for the whole of 1999. For a limited time, it also allowed developers to resell government land that they were no longer able to develop.

Developers began to slash prices of unsold inventory and launched new projects under benchmark prices, some offering to absorb stamp duty payments as well. Prices dropped 13.5 per cent in Q3 1998, marking their largest quarterly decline in 30 years. From mid-1996 to end-1998, the index fell 45 per cent.

On the upside, an academic study showed that the affordability of private property improved: The average price of condos and apartments had fallen from the Q3 1996 peak of S$868 psf to S$579 psf in Q2 1998. Singapore’s GDP per capita at constant prices rose from S$27,494 to S$29,797 during the same period.

Back in Q1 1992, the average price was S$388 psf, but per capita income at constant prices was much lower, at S$18,420.

The price cuts brought buyers back. By the end of 1999, transaction volume had surged back up to over 20,000 units, higher than in 1996 when the government first stepped in. Prices had bounced up 34 per cent.

2000-2007

The optimism soon withered as markets were thrown by several external shocks from 2000. Singapore fell into a recession in 2001.

The government again cut land sales. It also lifted earlier restrictions on Singapore dollar housing loans to foreigners and non-Singapore companies, while capping banks’ property-related exposure to 35 per cent of total eligible assets.

In November 2001, it extended a deferred payment scheme (DPS) that was first introduced in 1997. This allowed developers to defer up to half of the initial 20 per cent down payment up to the issuance of Temporary Occupation Permit or any time before that.

Amid the recessionary climate, buyers retreated and private home prices slipped 20 per cent between 2000 and 2004, during which global economies slumped after the dotcom bust, the terrorist attacks of Sep 11, 2001, a worldwide electronics slowdown, the SARS pandemic and the Iraq war.

Home sales fell to a low of 10,699 units in 2003.

Another rollback of financing curbs was introduced in 2005: The LTV limit for housing loans was raised from 80 to 90 per cent, and the minimum cash down payment cut from 10 to 5 per cent.

During the year, the government announced that Singapore would have two integrated resorts with casinos. The anticipated spinoffs, along with relaxed immigration policy, brought a wave of foreign investors betting on the country’s growth.

“In 2005, the government announced that Singapore would have two integrated resorts with casinos. The anticipated spinoffs, along with relaxed immigration policy, brought a wave of foreign investors betting on the country’s growth. ”

Prices rose 3.8 per cent in 2005, then 10 per cent in 2006. The St Regis Residences broke records with sales crossing S$3,000 psf.

By 2007, the market was scaling a fresh peak, with the economy notching strong 9 per cent GDP growth.

Prime Orchard Road properties began to cross the S$5,000 psf mark. New projects such as Cliveden at Grange, Hilltops and The Orchard Residences commanded over S$3,500 psf, versus Ardmore Park which had launched at about S$1,800 psf just over 10 years before.

The market surges prompted the government to act on Oct 26, 2007, pulling the plug on the deferred payment scheme.

By then, the US sub-prime mortgage crisis had begun to unfold, with widening fallout.

Prices slowed in the last quarter of 2007. Still, the earlier momentum fed into a 31 per cent full-year gain in prices, the fastest annual rise since 1999. Sales totalled an astounding 40,650 units, about 60 per cent more than in the year before. Developers chalked up a record 14,826 new units sold.

Speculators had come back in force, with 4,863 subsale deals in 2007, almost 10 per cent of all private property sales in the year. (The previous high-water mark was in 1996, when 3,622 subsale transactions were recorded and one in five deals involved a subsale flip.)

Rents too jumped in 2007, as the stock of completed private homes dwindled – the result of developers turning cautious in 2003 to 2004, and putting off building new projects. Rents of condos and apartments rose more than 40 per cent across the island.

The HDB market was also heating up. Resale prices rose 17.5 per cent in 2007, and in January 2008, an executive flat along Mei Ling Street in Queenstown sold for a record S$890,000.

2008-2013

The scrapping of the DPS in Q4 2007 sent the roaring market into retreat. To win back buyers, banks and developers began to resurface a form of deferred payment, offering an interest absorption scheme early in 2008.

But sentiment remained weak. Developers delayed launches. The US sub-prime crisis degenerated into a full-blown financial market meltdown in 2008. Fears of a major US recession sent stock markets free-falling. Lehman Brothers went bust.

The HDB’s 50-storey Pinnacle@Duxton raised eyebrows when the project’s last batch of five-room units was put up for sale from S$545,000 to S$645,800.

By mid-2008, Singapore’s property market had started to correct, dipping over 2 per cent in Q3 before diving 6 per cent in Q4, bringing an end to a boom cycle that started in 2004.

By Q4 2008, the country was in recession, dragged down by the global financial crisis. Over the course of the year, the combined market capitalisation of Singapore-listed equities shed half its value, falling from S$790 billion at end-2007 to S$393 billion at end-2008. Jittery investors fled stocks and nursed huge losses.

Developers sold just over 4,600 units for the year, the lowest new home sales tally seen in 13 years. Bids for state land were soft and sparse, while en bloc sales flopped.

Nevertheless, Singapore was now firmly on the radar of the global wealthy. Formula One’s first-ever night race opened to much fanfare in September 2008, with 100,000 tickets sold.

Post crisis, the massive fiscal and monetary stimulus in major economies boosted liquidity, which soon began to circulate again.

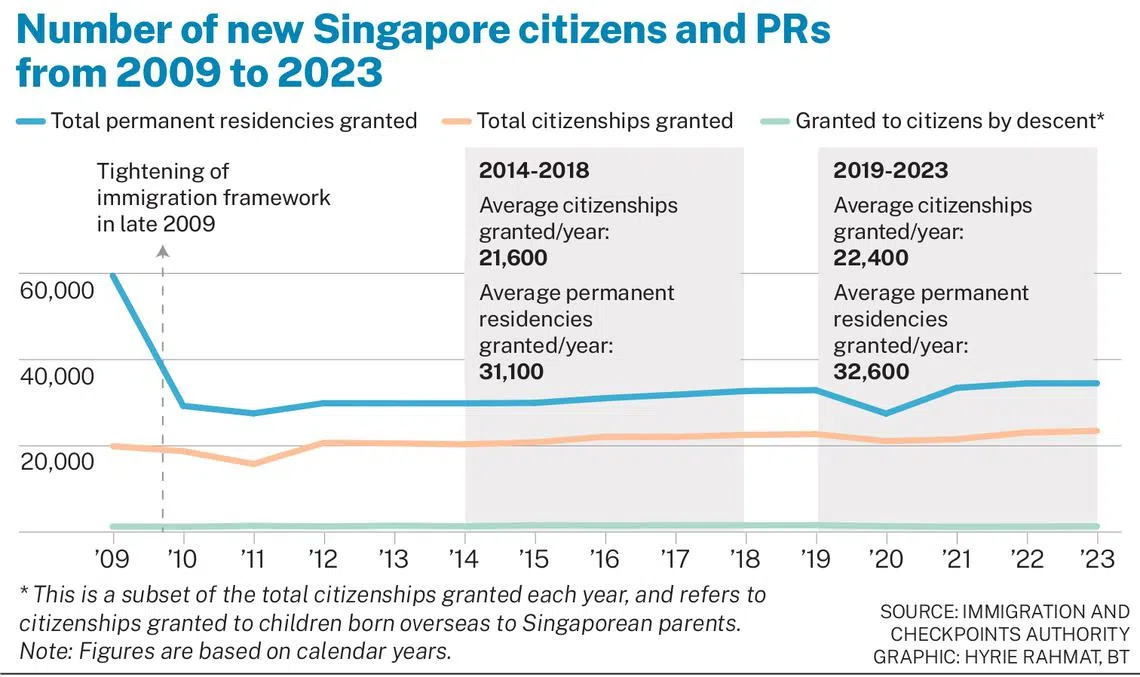

The year 2008 also saw a peak in the number of permanent residencies granted by the government. New PRs totalled 79,167 that year; another 20,513 were granted citizenship.

Come 2009, buyers had returned, sending Singapore property prices shooting back up. Volumes rebounded, jumping 2.5 times from their 2008 low to over 33,000 units in 2009. The strong take-up led to the index recovering 38 per cent in four quarters.

“The year 2008 also saw a peak in the number of permanent residencies granted by the government. New PRs totalled 79,167 that year; another 20,513 were granted citizenship. ”

In 2009, the government tightened Singapore’s immigration framework, cutting inflows. The number of permanent residencies halved in the year after, to just under 30,000 in 2010. (The PR tally rose slightly to average 31,100 a year between 2014 and 2018, and to 32,600 a year between 2019 and 2023.)

More cooling measures were rolled out from Q3 2009. In the following year, the GLS programme was stepped up to its highest supply ever.

September 2009

- Interest Absorption Scheme (IAS) and interest-only housing loans (IOL) abolished

February 2010

- SSD reintroduced at a rate of up to 3 per cent

- LTV limit tightened from 90 per cent to 80 per cent

August 2010

- SSD holding period increased from one year to three years

- For property buyers already holding one or more outstanding housing loans at the time of a new housing purchase, minimum cash payment raised from 5 per cent to 10 per cent

- LTV limit cut further from 80 per cent to 70 per cent

January 2011

- Holding period for imposition of SSD increased to four years, at rates ranging from 4 per cent to 16 per cent

- LTV limit tightened for homebuyers with one or more outstanding housing loans; to 50 per cent for non-individual buyers, such as companies

December 2011

- Additional buyer’s stamp duty (ABSD) introduced, over and above the buyer’s stamp duty (BSD), for residential property

- Highest ABSD of 10 per cent applied to foreigners and non-individuals buying any residential property

- Citizens pay 3 per cent ABSD on their third and subsequent properties

- PRs pay 3 per cent ABSD on their second and subsequent properties

- Foreigners of certain nationalities falling within the scope of free trade agreements accorded the same treatment as Singapore citizens: nationals and PRs of the US, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Iceland

October 2012

- Maximum tenure of all new housing loans capped at 35 years, with tighter limits on certain categories loans

- LTV limit for housing loans to non-individual borrowers cut to 40 per cent from 50 per cent

January 2013

- ABSD raised by five to seven percentage points across the board

- ABSD imposed on PRs buying their first residential property and on citizens buying their second residential property

- Foreigners pay 15 per cent ABSD for any residential property purchase

- Tighter LTV limits on housing loans to individuals who already have at least one outstanding housing loan, and to non-individual borrowers

- Minimum cash down payment for individuals applying for a second or subsequent housing loan raised from 10 per cent to 25 per cent

“Through seven rounds of cooling measures rolled out every year from 2009 to 2012, the market stayed buoyant. Home sales rang in well above the 30,000-a-year mark. What changed the game was the TDSR framework, put in place in 2013.”

The market stayed buoyant. Through seven rounds of cooling measures rolled out every year from 2009 to 2012, home sales stayed well above the 30,000-a-year mark.

What changed the game was the introduction of the Total Debt Servicing Ratio (TDSR) framework, which remains in place today.

June 2013

- TDSR framework mandated. Financial institutions granting new property loans to individuals must ensure a borrower’s total monthly debt obligations (including car loan and credit card repayments) do not exceed 60 per cent of gross monthly income

- LTV rules refined to prevent circumvention of limits on second and subsequent housing loans

New home sales fell by half after TDSR kicked in, taking total sales down to 12,847 units, close to the previous crisis-period level seen in 2008.

2013-2017

Between 2013 and 2017, prices fell 12 per cent over 15 quarters.

At the same time, the average income of employed resident households grew 14.9 per cent. Private property was becoming more affordable.

Earlier cuts in GLS supply to allow the market to absorb unsold stock had resulted in a dearth of new projects by end-2016. Developers turned to collective sales to stock land banks.

Thus began the en bloc sale frenzy, starting from mid-2016 and extending until 2019; this also put more buying power into the hands of condo owners, who pocketed windfall gains from their collective sales.

In March 2017, the government eased the SSD regime and tweaked the TDSR for certain loans. By the end of 2017, volume had jumped to just over 25,000 units for the year, up 50 per cent from 2016. Prices rose 9.6 per cent in five quarters, all but erasing the 12 per cent decline that had unfolded over almost four years.

Land prices were also rising rapidly, as developers mopped up en bloc sites. A number of the collective sale sites were in high-value prime Districts 9, 10 and 11, as well as former Housing and Urban Development Company developments in coveted heartland locations.

Meanwhile, Singapore’s population was steadily increasing, reaching 5.61 million in 2016 from 5.47 million in 2014.

From 2017, the market also began to see high-profile, high-value deals involving Chinese buyers or funds, picking up both prime properties as well as commercial property – office space and shophouses.

Deals that made headlines included an extraordinary block deal of 19 units at Canninghill Piers for S$85 million in 2022. Some of these eye-popping purchases were eventually linked to a syndicate of Fujian money launderers busted in a police dragnet in August 2023.

2018-2023

The market’s recovery party was cut short when, in July 2018, ABSD rates went up again. Crowds thronged show-flats the night before the new rates kicked in, prompting the government to change tack on future announcements, releasing information only at midnight.

July 2018

- ABSD for citizens and PRs buying their second or subsequent residential property increased by five percentage points

- ABSD for foreigners increased to 20 per cent for any residential property purchase, from 15 per cent

- Entities buying residential property to pay 25 per cent ABSD, up from 15 per cent

- Developers buying residential properties for housing development to pay a non-remittable ABSD of 5 per cent upfront upon purchase

- LTV limits tightened by five percentage points for housing loans

Against wider economic uncertainty – the US-China trade war and an unsure path to Brexit, the private property price index continued to rise, even as volume fell back.

Then Covid struck at the end of 2019. With the pandemic came unprecedented restrictions on movements of goods, supply of materials, and people.

Singapore put in place its “circuit breaker” between Apr 7 and Jun 1, 2020. Schools shut, workplaces of all non-essential businesses and services closed, and work-from-home was instituted.

The government extended construction and other development timelines. It was only in April 2022 that Covid restrictions were relaxed and borders reopened.

Contrary to expectations that demand would slow and prices would cool, homes sales picked up from June 2020 when show-flats were allowed to reopen with safe distancing measures.

Developers were dishing out “star buys” and discounts. Buyers looking for immediately available homes ploughed into the resale market – both to buy and to rent – when construction delays disrupted their plans.

The result was a surge in sales. New home sales topped just over 13,000 in 2021, the highest since 2013, while resale volume reached almost 20,000, the highest since the 2007 peak. Prices rose 10.6 per cent in 2021.

The government moved to hike ABSD rates again, targeting investment demand.

December 2021

- ABSD for citizens purchasing their second residential property raised to 17 per cent, and to 25 per cent for their third and subsequent properties

- ABSD for PRs purchasing their third and subsequent property raised to 30 per cent

- ABSD for foreigners purchasing any residential property raised to 30 per cent

- ABSD for entities and developers purchasing any residential property raised to 35 per cent

- TDSR threshold tightened by 5 percentage points from 60 per cent to 55 per cent

In the year that followed, inflationary pressures, rising interest rates and a lack of new launches combined to erode sentiment. Volume fell by 35 per cent to 21,890 units in 2022.

Prices rose 8.6 per cent through the year, slightly slower than in 2021. Rents, meanwhile, surged 30 per cent.

September 2022 brought new measures to encourage “prudent borrowing” and dampen buying sentiment.

September 2022

- Fifteen-month wait-out period introduced for private residential owners intending to buy an HDB resale flat after selling their private property (not applicable to those aged 55 or older intending to buy a four-room or smaller flat)

- LTV limit for HDB loans reduced from 85 per cent to 80 per cent

- HDB loan interest rate raised from 2.6 per cent to 3 per cent

- Medium-term interest rate floor used to compute TDSR raised

Singapore’s population was also growing again, after falling 4 per cent in 2021 during the pandemic as borders closed.

Numbers of non-PR foreigners rose from a low of 1.47 million in 2021 to 1.77 million in 2023. The Republic’s total population went up from 5.45 million in 2021 to 5.92 million in 2023 – and would rise further to 6.04 million as at June 2024, 2 per cent higher than in June 2023. The increase was mainly due to growth in the non-resident population.

Purchases by foreigners and PRs grew from 7 per cent of all home sales in 2021 to 10 per cent in 2022, then rose further to 12 per cent in Q1 2023. The government raised ABSD rates further.

The authorities acknowledged that the December 2021 and September 2022 measures had had a moderating effect, but prices were starting to accelerate in Q1 2023.

“Demand from locals purchasing homes for owner-occupation has been especially strong, and there has also been renewed interest from local and foreign investors in our residential property market,” a government statement said.

“Prices could run ahead of economic fundamentals, with the risk of a sustained increase in prices relative to incomes.”

April 2023

- ABSD for citizens purchasing their second residential property raised to 20 per cent, and to 30 per cent for their third and subsequent properties

- ABSD for PRs purchasing residential property set at 5 per cent for their first, 30 per cent for their second, and 35 per cent for their third and subsequent purchases

- ABSD for foreigners purchasing any residential property doubled to 60 per cent from 30 per cent

- ABSD for entities purchasing any residential property raised to 65 per cent

In August 2023, 10 Chinese individuals were rounded up in a pre-dawn raid and busted for money laundering.

An initial estimate put the value of assets seized at S$1 billion, with 105 properties including bungalows in Sentosa Cove, luxury condos and commercial and industrial properties estimated to be worth S$831 million, as well as cash in Singapore bank accounts and cryptocurrencies.

As investigations continued, it emerged that up to S$3 billion in assets had been seized. BT also reported that the suspects had been picking up Singapore properties since at least 2017, and individuals from “higher risk” countries had bought hundreds of properties since 2016.

Stricter guidelines came into play concerning high-value transactions, fund transfers and suspicious deals.

2024-2025

The steep hike in ABSD implemented in 2023 – and the stricter compliance required for high-value deals – kept foreign buyers at bay. Foreigners accounted for just 1 per cent of all homes transacted in 2024.

The various other ABSD measures aimed at tamping down demand, combined with constant signalling of higher future supply, resulted in developer sales shrinking in 2023 and 2024 to about 6,400 units a year – their lowest levels in 15 years.

Price momentum slowed. The index gained just 3.9 per cent in 2024 after rising 6.8 per cent in 2023.

A fresh spurt of buying in Q4 2024 and Q1 2025 lifted sales and sentiment as attractive new projects were marketed, but caution returned after US President Donald Trump’s tariffs landed on Apr 1.

In July 2025, the government sent a warning shot to speculators, tightening the SSD regime with higher rates and extending the applicable holding period. The SSD framework had earlier been relaxed in 2017.

While not couched as a cooling measure, the move was in response to a sharp increase in the number of private residential transactions with short holding periods in recent years, MND said.

Prices are up 1.8 per cent for the first half so far this year. Analysts forecast a 3 to 5 per cent rise for the year, with a long pipeline of launches slated for H2 and interest rates easing.

Developers’ sales could come in between 7,000 and 9,000 units, higher than last year’s tally but still a far cry from their 2012 peak of 22,197.

Against ever-present concerns about affordability, local household finances have strengthened as Singapore’s economy grew, developed and transformed.

At end-1995, household liquid assets (comprising currency and deposits, shares and securities, and pension funds) totalled S$152.1 billion, with total liabilities at S$77.3 billion – 51 per cent of liquid assets.

At end-2024, Singapore households’ balance sheet was much healthier with total liabilities, at S$378.3 billion, accounting for 37 per cent of total liquid assets of S$1.03 trillion.

The economic outlook has also firmed after earlier concerns of a tariff-induced slowdown. While the official growth forecast remains at 0 to 2 per cent, economists think growth may top 2 per cent this year.

Between 1980 and 2024, the URA’s home price index rose almost eight times even as cooling measures were increasingly stepped up. Compounded, the annual growth in home prices was 5.1 per cent.

A July 2025 report by the Urban Land Institute (ULI) puts private home prices in Singapore at 16.9 times the annual median household income, with an average price of US$1.7 million, or S$2.2 million at current exchange rates.

Singapore private property is now among the most expensive homes in the region.

The vast majority of Singaporeans, however, own public housing flats, which the ULI put at 4.3 times the median annual household income in 2024, within the level widely regarded as affordable.

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.