Tokenisation of real estate – is it real estate securitisation 2.0?

TECHNOLOGICAL advancements in computing power and cloud-based data sharing are revolutionising how information is collected, processed and disseminated. They could also potentially disrupt how social networks and business activities are conducted in the real world. But at the same time, they open up a whole new range of opportunities in the virtual world.

The recent news of million-dollar transactions involving virtual lands in the metaverse and digital artworks has attracted excitement in the real world. However, it is still puzzling why those real-world investors were willing to pay so much to own such assets. How will virtual lands derive demand and create value in the metaverse for real-world investors?

Is the (virtual) metaverse market a transient hype that will be short-lived, or will it be the next big thing that will shake up real markets? It is still early days for any verdict.

The recent cryptocurrency crashes may have spooked some investors. However, it does not seem to have deterred investors from wanting to invest more in virtual assets. Are they not worried that their investments will dissipate in value?

Blockchain and non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are the two key building blocks that underpin and drive economic activities in the virtual world. However, these were merely buzzwords to many who are unfamiliar with the technology.

This article will examine how these technologies were adopted in recent developments in real estate tokenisation. Will the process gain traction here? What are the potential risks and challenges going forward?

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

What is real estate tokenisation?

Real estate is inherently immobile, indivisible and illiquid by nature. Converting illiquid real estate into liquid tradeable securities – a process known as securitisation – can be traced back to the 1960s in the United States. The concept of fractional ownership gave rise to the real estate investment trust (Reit) that allows investors opportunities to invest and jointly own an equal, undivided interest in income-generating commercial real estate.

Tokenisation shares some similarities with the securitisation process. In tokenisation, property interests are divided into small units, each represented by a virtual token instead of a security. Unlike Reit units that are issued and traded via a centralised exchange, these tokens are tradeable over a blockchain network, Ethereum or Bitcoin.

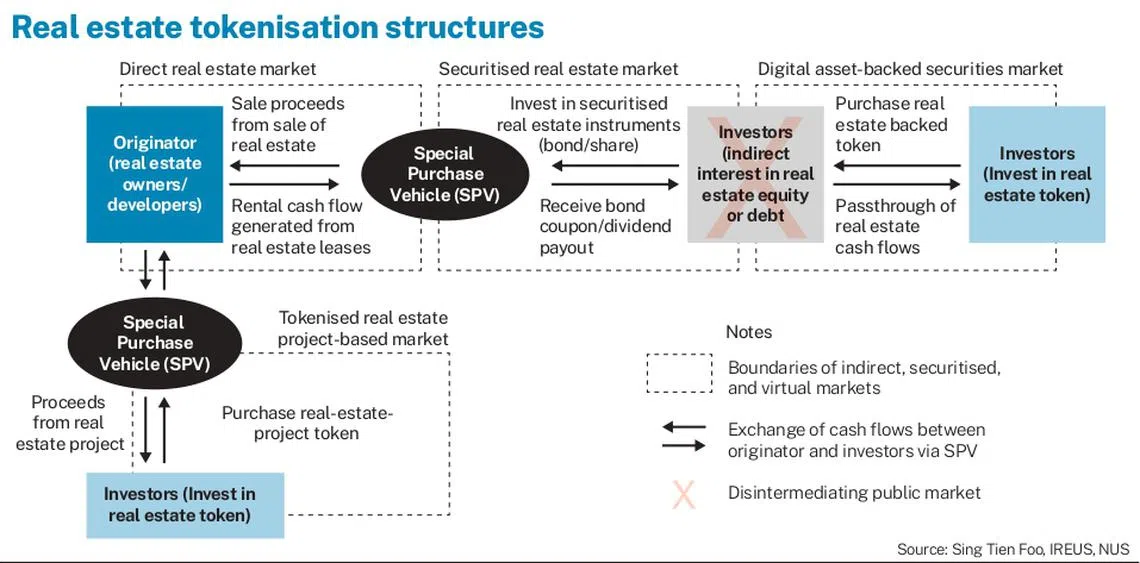

The securitisation process starts by identifying potential real estate for acquisitions, and in some cases, multiple real estate assets are pooled to form a portfolio for scale economics. Like Reits, the portfolio usually consists of mature real estate that generates stable rental income. The next step before security issuance is to create a bankruptcy-remote structure by transferring the real estate portfolio to a special purpose vehicle (SPV). The process up to this point is similar for both securitisation and tokenisation.

In a typical Reit structure, securities that are freely tradeable on a public exchange will be issued and distributed in an initial public offering (IPO) process. However, on a blockchain platform, digital asset-backed securities (DABS) are issued and distributed in a process known as security token offering (STO).

In May 2022, CitaDAO, a digital real estate platform, tokenised Midview City, an industrial property in Singapore, to raise US$617,647, a process which it calls “introducing real estate on-chain” (IRO). Sponsors could also use digitalised securities to supplement but not fully replace the funding source from the capital market. For example, in May 2021, Mapletree Investment tokenised part of its private Reit - Mapletree Europe Income Trust (Merit) via the iSTOX platform.

In Singapore, qualified issuers of STO must obtain a Capital Markets Services (CMS) licence from the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS). Fraxtor, Kasa, and RealVantage are some real estate tokenisation issuers with CMS licences. Under the Securities and Futures Act (SFA), MAS restricts token investments to only accredited investors who have net personal assets exceeding S$2 million, or earn an income in the preceding 12 months of not less than S$300,000.

The real estate blockchain structure is not just restricted to DABS. The diagram above shows an alternative structure on how a developer uses tokenisation to fund a real estate development project. He pools investors’ funds through an SPV and co-invests them in real estate development projects. Straits Trading, for instance, raised S$24 million last year by tokenising a 64-storey high-rise residential development in the Central Business District of Melbourne, Australia. Fraxtor tokenised two redevelopment projects in Singapore: freehold site Gloria Mansion in Pasir Panjang Road and a bungalow site at Mount Rosie Road.

Motivations of stakeholders in tokenisation

There are three different real estate markets – direct, securitised, and tokenised markets. Tokenisation and securitisation help overcome divisibility and liquidity constraints inherent in direct real estate investments.

How different are DABS from typical Reits, other than being issued in different securities? The motivations for tokenisation may differ among stakeholders ranging from real estate owners/sponsors to digital services providers and investors.

Tokenisation, or more broadly decentralised finance (Defi), offers an efficient way of fundraising for real estate owners by cutting down intermediaries, thereby reducing transaction costs.

However, extending fragmented real estate to retail investors alone is not enough to motivate sponsors to move their real estate from the Reit to the blockchain platform. Sponsors’ motive for setting up a Reit is not a one-off fundraising exercise, but to create a channel for future asset injection. In this sense, the closed-end fund structure in single real estate tokenisations is harder to deploy for managing real estate portfolios.

Without a liquidity crunch in Reit markets, real estate sponsors need incremental value-adds to move into real estate tokenisation as an alternative to the Reit market as the fundraising source.

To fintech firms, democratising commercial real estate investments by reducing the barrier of entry to retail investors via blockchain technology creates new business opportunities. However, friction may arise if tokenisation threatens to disintermediate financial service providers and sponsors from Reit businesses. These players will likely be disincentivised from moving real estate onto the virtual platform.

Retail investors could invest in commercial real estate by purchasing tokenised real estate interests with small capital outlays. However, tokenised real estate markets are highly volatile. The price discovery process on the Defi platform could move very fast and diverge from prices in the highly imperfect local real estate market. The price divergence creates arbitrage opportunities but also increases market risks.

This investment option may not be suitable for faint-hearted investors. The cryptocurrency crash in 2021 could signal potential risks for significant depreciation in token value backed by real estate. Therefore, only accredited investors with enough financial buffers are allowed to invest in tokenised real estate in Singapore.

Even as blockchain-based cryptocurrencies make headlines, for better or for worse, a good appreciation of blockchain and what it entails continues to elude many. More education and industrial outreach are necessary to bridge the knowledge gap and promote awareness among retail investors on the possible investment risks and potential in tokenised markets.

Is “Tokenisation” not “Securitisation 2.0”?

Tokenisation that only lowers entry barriers and raises efficiency is no different from securitisation. If the blockchain platform could help remove the “immovable” constraint, it could unlock more real estate value.

First, the “non-fungibility” feature creates value for assets in the metaverse, such as virtual land and digital artwork. However, creating uniqueness, scarcity and non-substitutability in real estate could be challenging. If investments are based only on claims of cash flows generated from real estate assets that are “fungible”, the cash flows should not be valued differently by the Reit and tokenised markets if both are efficient.

Second, investors rely on banks, agents and other professional service providers, such as lawyers, valuers and others, to provide intermediary services in direct real estate transactions. A “smart contract” is an immutable document that protects the ownership rights of token investors on the underlying real estate. It minimises frictions and distortions by intermediaries that may occur in the transfer process.

Third, trust is a key factor in the blockchain world. The reputation of token issuers is as important as sponsors in the Reit market to give confidence to investors. “Skin in the game”, such as retaining a substantial stake by sponsors, could align interests between sponsors and fractional investors in tokenised issuance, as in Reit issuance.

Some advocates of blockchain technology have touted real estate tokenisation to bring the real estate capital market onto the next lap. Tokenisation brings fundraising from the capital market to the Defi world. However, it is unlikely to substitute the capital market in the short term. The two markets will co-exist to provide diverse funding sources to real estate markets. Any change, if expected, could only be deemed in a narrow sense as “Securitisation 2.0”.

The writer is a professor at the department of real estate, business school, and the director of the Institute of Real Estate and Urban Studies (IREUS), at the National University of Singapore. The views and opinions in the article are the author’s and do not represent the views and opinions of the author’s affiliated institutions.

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.