Singapore drops ‘30 by 30’ farming goal, sets revised targets for fibre and protein by 2035

At the same time, the government is also exploring new ways to help local farms boost production and stay viable

[SINGAPORE] Singapore has replaced its original 2030 farming goals with new targets for fibre and protein production by 2035, amid headwinds confronting the local agricultural sector.

At the same time, the government is also exploring new ways to help local farms boost production and stay viable. It will, for instance, be studying the feasibility of developing a facility that can host multiple farms, and provide common utilities and shared services to lower production costs.

Minister for Sustainability and the Environment Grace Fu announced the revised targets and new initiatives at the opening of the Asia-Pacific Agri-Food Innovation Summit on Tuesday (Nov 4).

This follows a year-long review of the goal for Singapore to by 2030 locally produce 30 per cent of Singapore’s nutritional needs, which includes fish, eggs and vegetables.

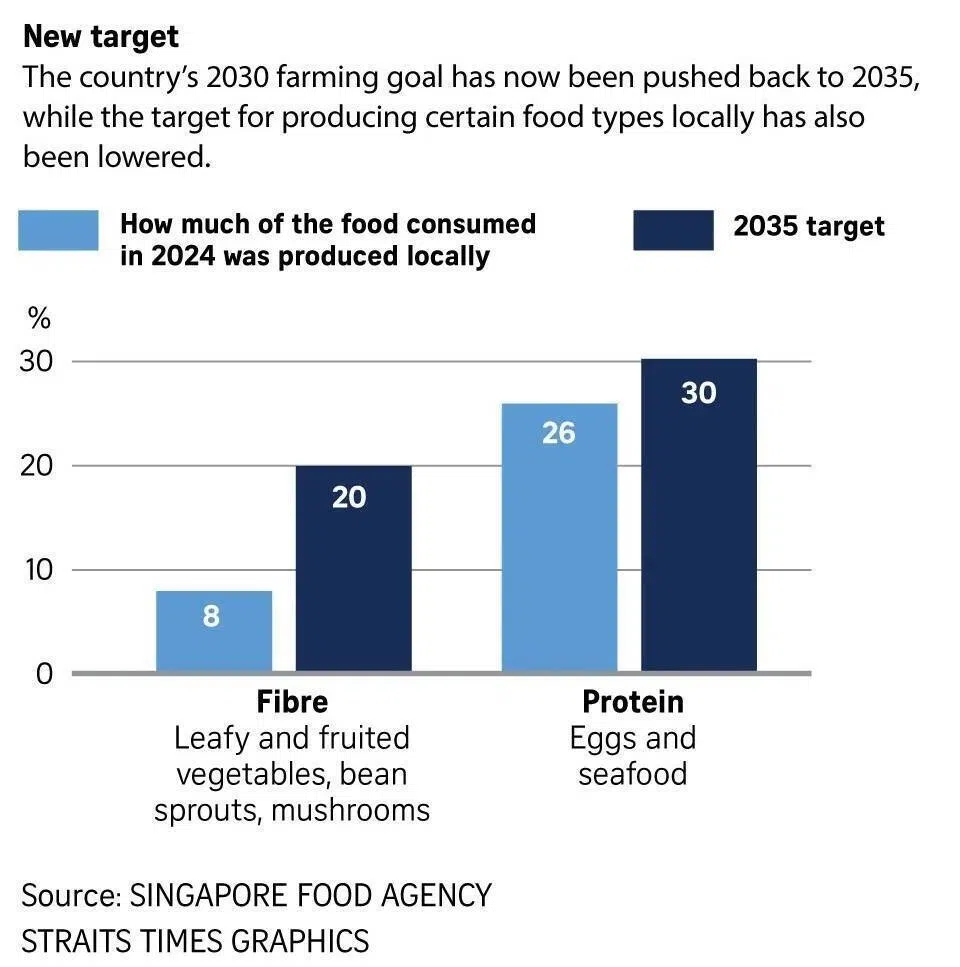

One of the new targets is for Singapore to by 2035 produce 20 per cent of the country’s consumption of fibre – a category that comprises leafy and fruited vegetables, bean sprouts and mushrooms, said Fu. These items can be commercially produced in Singapore.

Another goal is for local production of protein – a category which now comprises both eggs and seafood – to meet 30 per cent of total domestic consumption by the same timeline.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

In 2024, about 8 per cent of fibre consumed in the Republic was produced domestically. The figure for protein stood at 26 per cent, according to the Singapore Food Agency (SFA).

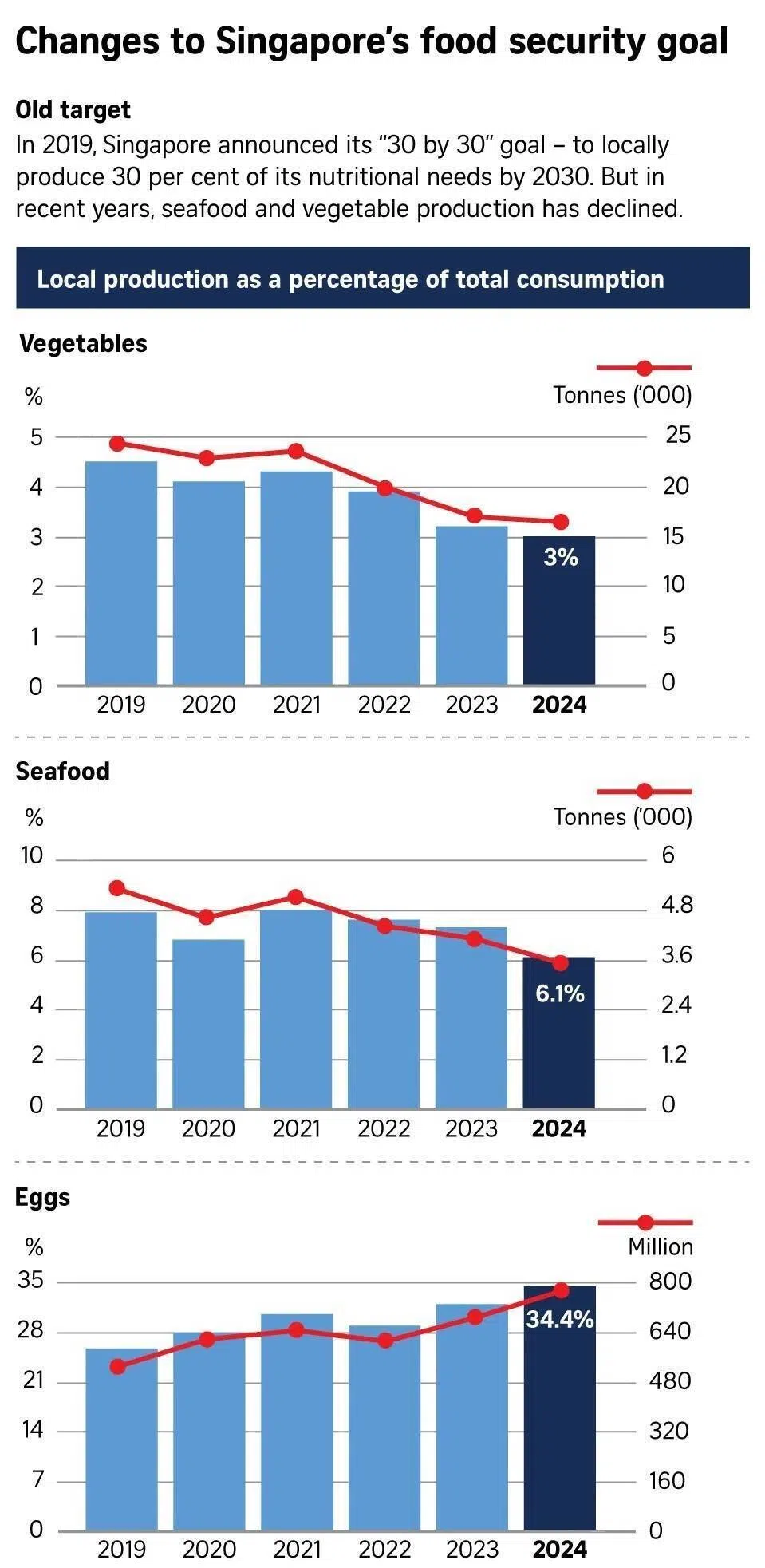

However, in June, a report on food statistics for 2024 produced by the SFA showed that only 3 per cent of vegetables consumed here were farmed locally.

SFA clarified that the fibre category now includes fewer vegetable types, with rooted veggies and bulbs omitted. Hence, the 2024 percentage was derived to be 8 per cent.

The June report had also shown that 34.4 per cent of eggs and 6.1 per cent of seafood consumed here were farmed locally in 2024.

SFA said the 26 per cent figure for protein was derived by combining the proportion of locally produced eggs and a smaller group of seafood, specifically fish and crustaceans.

Singapore’s food production aspirations

The original “30 by 30” goal was announced in 2019. At that time, the Covid-19 pandemic and associated supply chain breakdowns had not yet impacted the sector, and investor confidence on innovative farming techniques was high.

“We acknowledged that this was a challenging aspiration given our small and under-developed agri-food sector, our limited land resources and high operating cost environment,” said Fu at the Sands Expo and Convention Centre, the venue for the Singapore International Agri-Food Week.

About 1 per cent of land in Singapore is set aside for agricultural purposes.

But local farms have in recent years been plagued with a series of setbacks, from production declines to farm closures – especially for high-tech greens and aquaculture farms.

In the past couple years, some agri-tech firms such as I.F.F.I and VertiVegies have had to shut down or scrap plans to set up indoor farms. A quarter of sea-based farms exited in 2024 because of the higher costs of maintaining the farms and the need to pay for the use of sea spaces under a recent scheme, among other reasons.

Fu said: “Our local agri-food sector, like their peers in other countries, has faced headwinds – supply chain disruptions, inflationary pressures on energy and manpower costs, and a tougher financing environment.

“This has led to delays in farm development and some exits, even as we witnessed new start-ups.”

With food security being critical for Singapore, Fu outlined the nation’s new four-pronged strategy to ensure this.

They include: diversifying imports, local production, stockpiling, and a new pillar called global partnerships.

Global partnerships refer to government-to-government agreements with countries to strengthen food trade.

Some of the pacts could provide assurance that there would not be trade restrictions imposed on food items. Such an incident happened in 2022, when Malaysia imposed a chicken export ban for a few months as it was struggling to meet its own poultry needs.

This assurance sets this new pillar apart from Singapore’s primary food security strategy of diversifying its imports. The Republic currently imports food from more than 180 countries.

In October, Singapore forged the first of such deals with Vietnam on rice and New Zealand on essential food items.

“We are also exploring other international partnerships to boost our food security and will share more information when ready,” said Fu.

Stockpiling, the final pillar of Singapore’s food security approach, provides ready food stocks but is limited to food with longer shelf life, such as rice, frozen chicken and canned food.

Not giving up on local farms

Fu said that to further support urban farms and help reduce their production costs – a key obstacle preventing many from scaling up – SFA is doing a feasibility study on a multi-tenant facility where multiple types of farms can operate under one roof and share resources.

If this facility, which could possibly be government-owned, is realised, it could be the first of its kind in the world, said SFA’s chief executive Damian Chan in an interview with the media on Oct 30, ahead of the announcements.

Types of farms could include land-based aquaculture and greenhouses, he said.

If farms’ production costs are reduced with the facility, local farmers can lower the prices of their produce and increase sales, he added. The shared services in the facilities could include centralised utilities, packing and processing areas, and logistics.

“It will also help lower the regulatory hurdles which today, many of our farms are facing when they want to start up new farms here in Singapore, and, of course, also lower some of their initial investment costs as well,” said Chan.

This feasibility study is expected to take one to 1.5 years, and SFA has started engaging farms who could be potential tenants, he said.

This facility is separate from the Lim Chu Kang high-tech agri-food hub that is still being looked into.

The 390ha hub was announced in 2020, but in late 2024, it was reported that this Lim Chu Kang masterplan, as well as construction work for the neighbouring Agri-Food Innovation Park, was delayed.

SFA said: “The feasibility study of the pilot multi-tenanted facility will inform longer-term plans to intensify limited agricultural land at Lim Chu Kang and support farms to grow in a climate-resilient and commercially viable manner.”

The study joins a slew of other initiatives that have started in recent months to help local farms cope with the upheaval in the sector. These include a programme to supply farms with healthier eggs and baby fish, and ways to link farmers with consistent customers like eateries and supermarkets.

Cultivated protein not part of food security strategy

At the height of the optimism in the agri-food sector, Singapore also made headlines around the world in 2020 for being the first country to approve the sale of a cultivated meat product.

But since then, the alternative protein industry – which includes cultivated and plant-based products – has faced hurdles in scaling up due to higher production costs and weaker than expected consumer acceptance globally, Fu said.

Therefore, alternative protein will not be part of Singapore’s food security strategy in the short-term, SFA said.

“In the longer-term, if and when alternative proteins becomes more competitive and mainstream globally, it can potentially contribute to our food security. In the meantime, we will press on with efforts in R&D and industry development for this sector,” added the agency. THE STRAITS TIMES

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.