💔 As a Gen Z, here’s why I’m against ILPs

Straight to your inbox. Money, career and life hacks to help young adults stay ahead.

🏬 One-stop shop

In theory, investment-linked plans (ILPs) make sense. They offer financial protection in the event anything happens to you while helping you grow your money at the same time.

In reality, I think they don’t do both of those things very well for two reasons.

- ILPs don’t give you the coverage you need

- There are cheaper ways of investing

I don’t know any friends of working age who haven’t been pitched an ILP in their lives. (If you’re one of them: HOW?)

Regardless, here’s a primer on how they typically work.

When you sign up for an ILP, the money you pay your insurance company (premiums) is used to pay for units in one or more investment funds of your choice (sub-funds).

From time to time, these units are sold to pay for your insurance coverage and other costs.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

A selling point is that such plans are a one-stop shop for your financial needs. They’re often also pitched as being flexible. Some ILPs allow you to tweak your insurance coverage as your needs change or make top-ups and partial withdrawals as you wish.

🛡️ 101 on 101s

In our parents’ time, ILPs were mainly for protection with an investing element tied to it. Today, many of the plans being marketed are known in the industry as 101 plans.

That’s because, in the event of death, the insurance company will pay out 101 per cent of the policy value or total premiums paid. In other words, a token sum of 1 per cent on top of the value of your investments. In some cases it’s 105 per cent – still not enough to be significant.

The Monetary Authority of Singapore, in its basic financial planning guide, suggests that Singaporeans buy insurance protection for death and total permanent disability worth nine times their annual income.

For a fresh graduate earning S$4,000 a month relying solely on a 101 ILP, he or she would need about S$427,700 in the plan to be sufficiently covered.

As I’ve written about before, my approach to insurance is to only buy insurance for things where the risk is too much for me to bear. If I already have that much money readily available for my dependents, I wouldn’t need to be paying for life insurance.

That’s why many have described ILPs as investment funds in an insurance wrapper. They’re technically an insurance policy, but many buy them for the purposes of investment.

Which brings me to my next point.

💸 Charges galore

I’ve personally suffered from massive headaches on multiple occasions trying to understand what I was paying for when my parents handed over ownership of an ILP that they had signed for me years ago. (I surrendered the policy after many Panadols.)

ILPs are complicated. Furthermore, the cost structures of different plans can vary.

In general, there are distribution costs, such as commissions.

There are also recurring fees, which can be higher than 4 per cent per year. These fees are sometimes called admin, policy or supplementary fees.

Like any investment fund, the fund management will also charge an annual fee.

As mentioned earlier, some plans allow you to make partial withdrawals or surrender your policy at any time. Depending on your plan, there may be high penalties when you do this in the early years of your plan.

Again, depending on your plan, you may also be charged for switching investment funds.

Before signing an ILP, you’ll likely be presented with a table showing how much your money would grow based on projected returns. Somewhere on that page, you’ll likely see a warning saying investments are subject to risks and not guaranteed.

That warning is not specific to ILPs. With any investment, nothing is guaranteed. The only thing you can control are fees.

In certain personal finance circles, there’s a popular saying: Buy term, invest the rest.

It means going with plain-vanilla term insurance, which has no cash value but costs less in premiums. The rest of the money saved from the lower premiums gets invested.

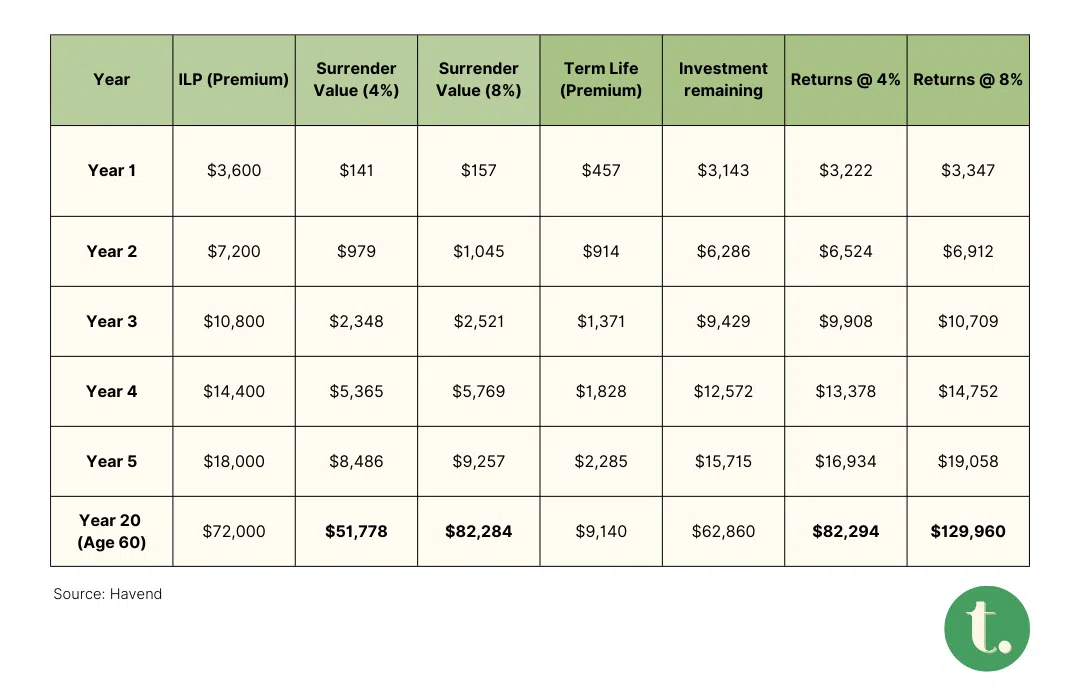

I’ll end off with a table that I found in an e-book published by Havend, an insurance advisory firm that prides itself on having salaried advisers who don’t receive sales incentives.

Here, the writers compare the portfolio of a 35-year-old non-smoker, who requires S$500,000 in insurance coverage if he were to buy an ILP versus choosing a term plan and investing the rest through an advisory that charges 1.5 per cent of his portfolio value every year.

TL;DR

- ILPs typically don’t guarantee returns

- The death benefit is funded mainly by premiums and may not even be guaranteed

- How they charge fees is often complex

- There may be high penalties for early withdrawal

thrive is the young audience initiative of The Business Times. Sign up for thrive’s weekly newsletter here. Follow on TikTok and Instagram for regular updates.

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.