If I’m “middle class”, why can’t I afford “middle-class things”?

Straight to your inbox. Money, career and life hacks to help young adults stay ahead.

[SINGAPORE] A friend said something to me over the weekend that I can’t stop thinking about.

We were talking about the unbelievably high Certificate of Entitlement (COE) prices – S$122,000 for a mass-market car – when she asked: “I’m pretty sure I’m middle-class. Why can’t I afford middle-class things?”

I don’t think she’s being delusional. She came from an “elite” school – the kind named after a certain Englishman credited with founding modern Singapore. In junior college, she received a private-sector scholarship to study at a top local university and has been in professional roles for five years.

But between saving for her future Build-To-Order flat and retirement, a car just isn’t realistic.

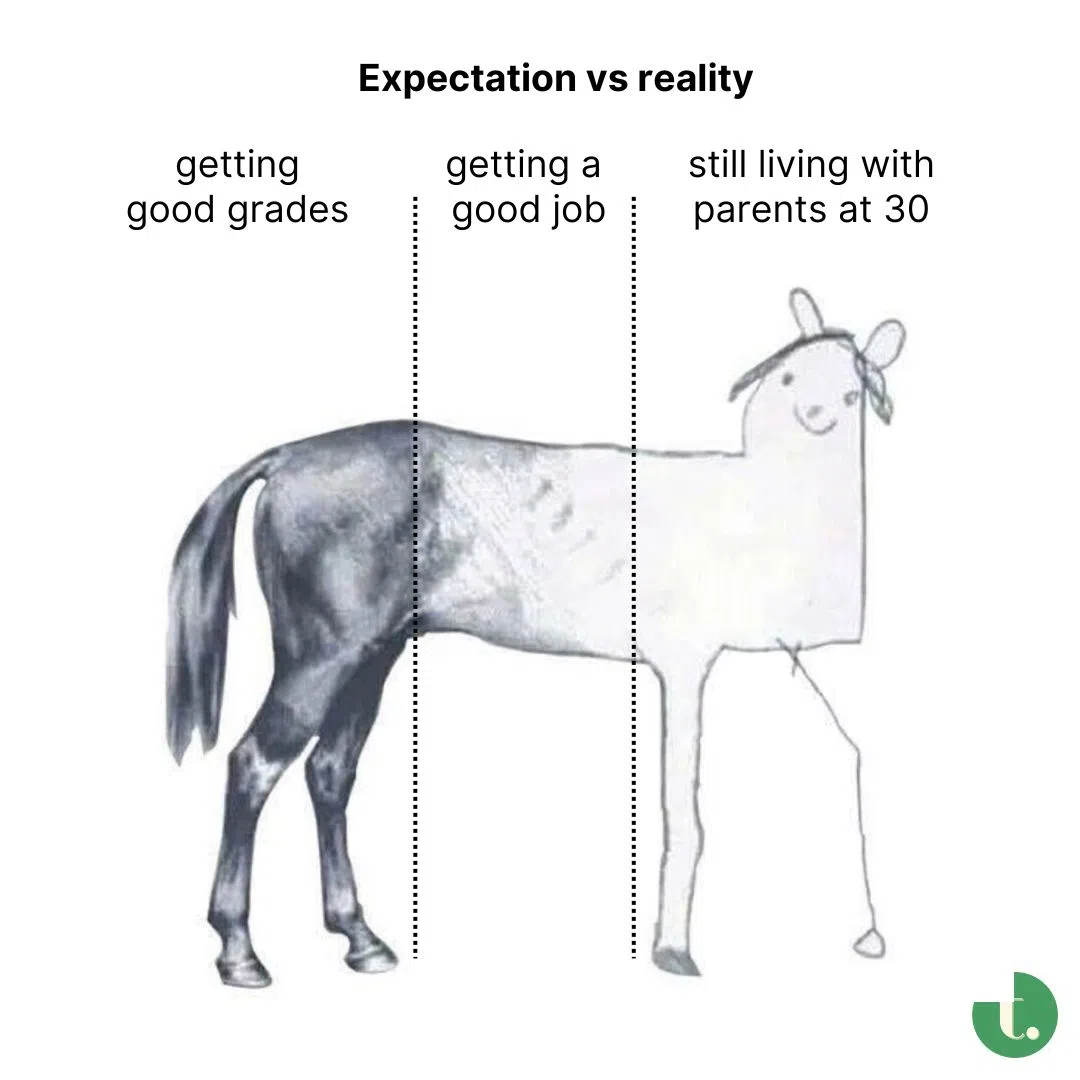

Among my own circle, this sense of disillusionment feels familiar. We were raised on the idea that if we studied hard, got into a good university, we’d get a good job and enjoy a good life.

That “good life” was basically the five Cs that make up what was one known as the “Singapore Dream” – cash, condo, car, credit card and country club.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

Our parents told us this because they were more or less achievable goals, if not for themselves, then for people around them who had university degrees. Some even managed it on a single income.

But for us these days, a car is out of reach, and the dream of upgrading from an HDB flat to a condo feels like a stretch.

🫅 What’s middle class anyway?

There isn’t a single definition of “middle class”, and some academics may consider education, occupation and social status. But let’s say we use income as a simple proxy. Official stats put the median gross monthly income for full-time employed residents at S$5,500 (including employer CPF) in 2024.

Now consider this: A new Toyota Corolla Altis starts at about S$193,888 according to Sgcarmart. With a seven-year loan at an interest rate of 2.48 per cent per year, that’s around S$2,709 per month – not counting petrol, taxes and other costs. Even for a dual-income couple, that’s a stretch.

It’s no wonder that fewer people are driving. About 33 per cent of Singaporean and permanent resident households owned cars in 2023, down from 40 per cent a decade ago.

From June 2004 to June 2024, median wages rose from S$2,326 to S$5,500, or an increase of 1.36 times. In comparison, prices for non-landed private homes went up by 2.84 times, while Category A COE premiums rose by 2.16 times, all over the same period.

So when someone who ticks all the “right boxes” – degree, stable job, decent pay – still can’t afford what they were told success would bring, it creates unhappiness and disappointment.

🐉 The myth of a middle-class lifestyle

When the five Cs are our expectations, it’s easy to slip into the thinking that: “I deserve this, so why can’t I get it?”

But maybe we need to be more realistic about our assumptions.

The five Cs were never benchmarks of a middle-class Singaporean. They were aspirations. If they were truly “middle class”, most people wouldn’t be living in HDB flats. Yet, since 1985, around 80 per cent of residents live in public housing.

So, why the disconnect?

Firstly, these expectations were born during a once-in-a-lifetime economic boom. From the late 1970s to the 1990s, incomes for ordinary households grew rapidly, and the economic boom created more opportunities for upward social mobility for an entire generation. It made sense then to believe that a degree was a ticket to material success.

But Singapore today is a mature, high-cost city. Global competition is fiercer, higher education is common, and social mobility has naturally slowed.

Secondly, the dream goods themselves have risen in cost. Cars and condos in Singapore are scarce by nature due to COE quotas and land constraints. As incomes rise, so too will the prices of these luxuries, beyond what a middle-class salary can afford.

⛈️ When expectations ≠ reality

When young people realise they won’t be able to afford what they thought they deserved, it hits their sense of self.

It’s that sense of frustration where they seem to be doing all the “right things”, and yet feeling like it’ll never be enough.

I believe that this mismatch partly explains why Singapore’s young adults rank as less happy than older generations in the World Happiness Report.

A psychiatrist who works with youth noted in a commentary that, among other reasons, some young people are awakening to a “daunting reality that, despite their best efforts, they are unlikely to surpass their parents’ success, in a society that has already reached remarkable heights”.

In recent years, the government itself has acknowledged that the Singapore Dream has shifted towards broader definitions of success. Instead of the five Cs, it’s more about purpose, relationships and contribution.

But if we’re honest, this shift is also pragmatic. Young people are coming to terms with the fact that these outdated material status symbols are seemingly more out of reach, so we start redefining what “success” means.

🖼️ Reframing our thinking

There’s nothing wrong with still wanting a car someday, or aspiring to private housing. But these should be conscious choices, not rites of passage.

It’s fair to question whether cars or private housing have become too unaffordable. But in your personal plan, base it on the world we live in, not the more idyllic one we imagine.

We should accept that a car is a luxury, not something you feel you deserve. If you truly want one, you’ll need a resilient financial plan that allows for it. Not everybody will be able to upgrade from an HDB flat to a condo, especially now that the government is tightening measures against short-term flipping of BTO flats for profit.

The more we fixate on what we think we deserve, the less satisfied we’ll feel. If we keep comparing our lives to outdated expectations, we’ll always come up short.

As for my friend, here’s what I eventually told her: You can’t afford middle-class things because they were never really middle-class things to begin with. Treat them as luxury goods. It’s better for your mental health that way.

TL;DR

- Among some young Singaporeans, there’s a sense of disillusionment about not being able to afford nice things despite checking the right boxes

- The five Cs defined the Singapore Dream, but they were aspirations, not markers of a middle-class life

- Today’s middle-income earners – who are priced out of luxuries like cars and condos – may find there’s a mismatch between old expectations and current realities

- We’ll be happier if we stop measuring our worth by what we think we deserve and start planning for the world we actually live in

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.