Bond lessons from the 1970s

IF you have lived and invested through the 1970s, you would recall what a dramatic time it was for bond investors.

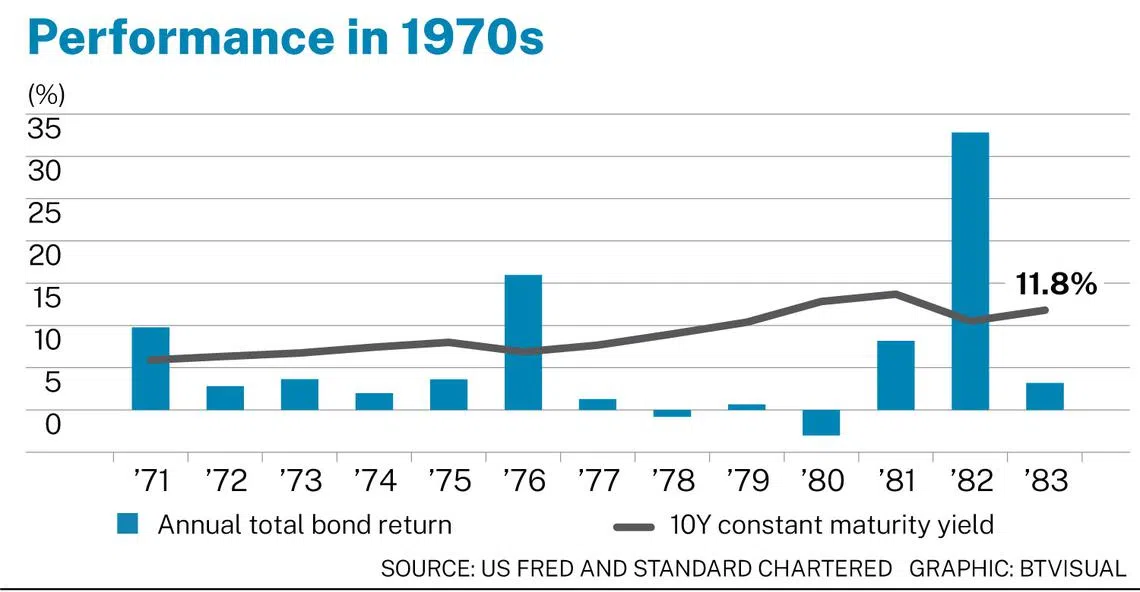

Back then, bond yields jumped from 6 per cent to a staggering 16 per cent in 1981 due to inflation, which soared from 2.8 per cent in 1972 to a peak of 14.8 per cent in 1980.

Today, Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell often uses the 1970s as a cautionary example of the risks of allowing high inflation to persist. After three decades of subdued inflation and interest rates, bond markets are beginning to realise what that historical reference means for long-term interest rates.

Surprisingly, a look back at bond returns in the 1970s reveals an interesting fact. US 10-year government bonds delivered mostly positive returns during that period. Though real returns were negative due to high inflation, investors rarely saw nominal losses. The worst annual drop was just 3 per cent in 1980. Don’t rising bond yields mean lower bond prices?

This apparent paradox was due to the high absolute coupon/yield during this period. Inflation was persistently above 5 per cent between 1973 and 1982. Bond prices fell as interest rates rose, but the substantial coupon helped offset the erosion of principal value.

This brings us to a crucial concept of bond duration, a metric that measures interest rate risk. A higher yield means lower risk as rates rise, while a lower yield indicates higher risk. Duration, measured in years, tells us how much a bond’s price changes when interest rates move. For example, a bond with a duration of seven years will decline by about 7 per cent when interest rates increase by one percentage point, and vice versa.

Now, let us look at today’s interest rate risk for different types of bonds:

*Only high-yield and floating-rate notes have yields exceeding their duration. This means their interest payment can offset price declines if yields move up by one percentage point. This explains why both assets have significantly outperformed Treasury and IG (investment-grade) corporate bonds this year amid rising yields.

*US aggregate bond and IG corporate bonds carry more interest rate risk compared to high-yield corporate bonds. Choosing between IG and high yield is not simply about credit quality but also about one’s tolerance for interest rate risk.

*Emerging market (EM) USD sovereign debt has a similar level of interest rate risk exposure as 7 to 10-year Treasuries. It offers 400 basis points higher in yield than 7 to 10-year Treasuries, but comes with EM country risks and is more susceptible to tighter liquidity from a stronger USD and rising rates.

Depending on your views on how the business cycle would evolve, one can potentially take two approaches:

1) Limit your exposure to interest rate risk by staying in shorter-duration bonds, which today offer a higher yield than longer-tenure bonds.

Unlike the 1970s where high yields shielded fixed income investors from significant nominal losses, current yields on longer-maturity bonds (beyond seven years) aren’t yet high enough to protect investors from seeing losses on a total-return basis, should yields continue to rise significantly.

Real yields in the pre-global financial crisis period ranged between 1.6 per cent and 2.65 per cent, averaging 2.1 per cent between 2004 and 2007. With real yields now at 2 per cent, further significant upside from here is arguably limited. The downside to this approach is the potential for reinvestment risks and missing out on capital gains when yields do eventually decline.

2) Add to some long-duration bonds, in the expectation that central banks are approaching an end in their rate-hiking cycle. Yields have likely peaked, and policymakers are expected to cut rates significantly as the US economy slips into a recession next year.

Historically, the Fed has slashed policy rates by at least 200 basis points in periods of recession. Lower yields will lead to higher bond prices. The downside of this approach is the potential for losses and greater volatility should yields rise significantly from here.

The writer is head of asset allocation and thematic strategy, Standard Chartered Bank

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.