The higher yields go, the further they’re likely to fall

For investors with a longer horizon, averaging into long-maturity government bonds at current yields may pay off handsomely

BOND yields, especially in the US, have risen sharply since mid-July, driven by US exceptionalism and “no-recession” narratives. While US data has undoubtedly outperformed market expectations, the recent run-up in yields is starting to look stretched.

Higher bond yields implicitly lead to tighter financial conditions and, when combined with slowdown in multiple data indicators, point towards a still-elevated risk of recession. The high bond yields are a sign of market complacency, in our view. Given this, averaging into long-maturity government bonds at current yields may pay off handsomely for investors with a multi-year horizon.

Taking stock of the bloodbath

The last three years have been extremely challenging for bond investors. Last year was the worst year for US government bonds since 1788. As things stand today, we are on track for the third consecutive year of negative returns on US government bonds – something that has never happened in the past 250 years.

Long-maturity bonds, with their high interest rate sensitivity, have borne the brunt of the sell-off. In fact, the zero-coupon long-maturity US government bond index is down more than 60 per cent from the peak in 2020. Is that justified?

Too complacent?

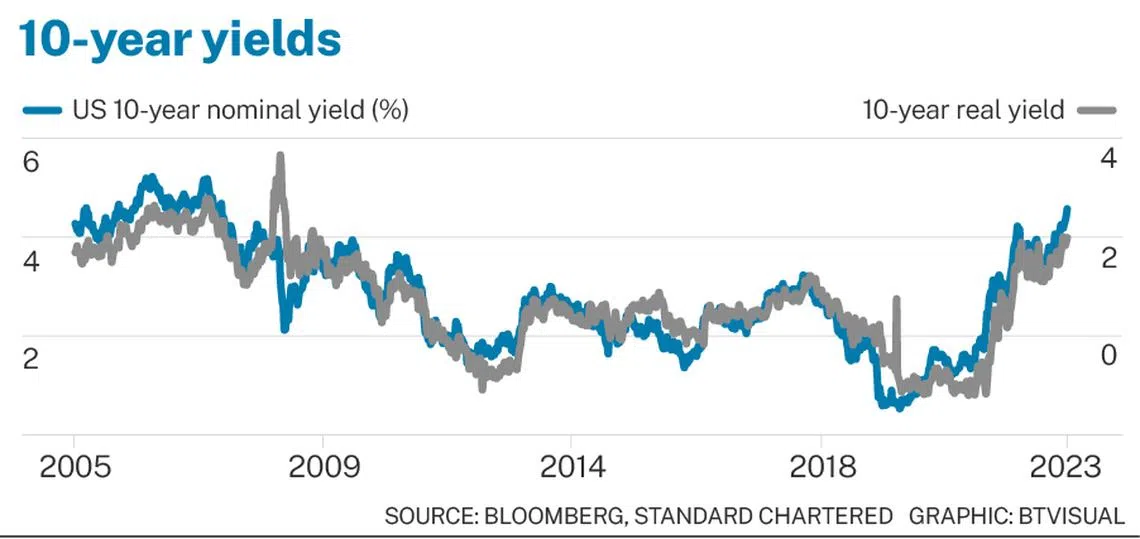

We believe markets are too complacent about the resilience of the US economy. Economic growth has exceeded expectations this year, driven by robust consumer spending. However, the recent surge in the 10-year US government bond yield to the highest level since 2007 begs the question of whether the magnitude of the rise is justified.

If we step back and have a look at macroeconomic theory, it tells us that high real (net of inflation) yields are indicative of tight monetary policy and generally act as a drag on growth. In 2023, market-implied expectations of long-term inflation have been relatively stable, which means that the recent rise in the nominal bond yield has been driven by a rise in the 10-year real (inflation-adjusted) yield to the highest level since 2008.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

With the Fed’s latest estimates reaffirming its view that 2.5 per cent remains the appropriate “neutral” policy rate over the long-term (that keeps the economy from over-heating or excessively cooling), the currently elevated 10- and 30-year bond yields are arguably telling us that monetary policy has significantly tightened, raising the probability of a recession over the next 12 to 18 months.

Ignore data at your own peril

Those who have watched the movie The Big Short may remember a famous line by the character Charlie Geller: “People hate to think about bad things, so they always underestimate their likelihood.” Most of us would like to see steady economic growth; indeed that is what most policymakers aspire to achieve. However, it is also important to look at hard economic data and what it is telling us.

We assign around 55 to 60 per cent probability of a mild US recession over the next 12 months. In our assessment, it is likely to be caused by:

- The long and variable lag of Fed tightening impacting US economic growth;

- Tight bank lending standards leading to slowdown in business investment and consumer spending;

- Slowdown in consumer spending as most US households have exhausted their excess savings built during the pandemic, while the resumption of student loan repayment crimps disposable income.

In fact, there has been a sharp uptick in US corporate bankruptcies, and auto loan and credit card delinquencies. All these point to possible cracks in the US economy.

Investment implications

While the recent rise in bond yields appears stretched in our assessment, it is certainly possible that momentum and positioning from trend-following investment strategies could push yields higher in the near term. However, if yields rise further or even stay at the current elevated levels for a significant period, it would increase the risk of a deeper and more prolonged recession in 2024.

For investors with medium- to long-term investment horizons (greater than 12 months), we believe that current levels offer an attractive opportunity to average into long-maturity, developed-market, investment-grade government bonds. The higher the bond yields go and the longer they stay there, the greater the probability that they will decline sharply, leading to higher bond prices next year and the year after.

The writer is a senior investment strategist at Standard Chartered Wealth Management CIO office

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.