Investing when the market has run up is hard, but here’s what helps

Loss aversion may be compelling, but a discipline of dollar-cost averaging can keep emotions at bay

POSITIVE stock market returns this year have surprised many, and the uptrend may well keep going, despite repeated calls for an early demise.

For investors who are waiting on the sidelines for a pullback so they can enter the market, the spectacle may be painful to watch. It is difficult to invest when the market is already up, because of a feeling of a perceived loss.

Let me explain.

Say an investor is looking to invest $1,000 in the market but ends up not investing it, and the market rallies 15 per cent. He would have gained $150 if he had gone ahead to invest, and this potential gain would weigh on him.

The reverse, of course, could have transpired: the market could have fallen, and by doing nothing, he would still have his original capital of $1,000.

Despite the alternative scenario, this investor would still feel like he lost $150. This is known as perceived loss. Instead of going ahead to invest the $1,000 because markets look better, he now tries to make back that $150 by rationalising that the market will pull back. This means he will set a target below current levels to get back in.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

If the market then rallies further – by say, 20 per cent from the beginning – the perceived loss would widen to $200 from $150, making it even more difficult to invest.

The theory of loss aversion or the fear of loss is a bias or phenomenon found in individuals, where real or possible loss is perceived as more severe than an equivalent gain.

For instance, the pain of losing $1,000 is often far greater than the joy of gaining that same amount in an investment. People say that the pain of losing is psychologically or emotionally twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining.

So, now we know what prevents us from taking action.

There are actually two issues at play.

First, investors worry that if they invest now, there is a risk the market reverses and falls, and they would lose money. Hence, they have loss aversion. The disposition effect is also at work. This refers to investors’ tendency to sell winning positions and hold onto losing positions, which contradicts the golden investing rule, which is to cut your losses and let your winners run.

Second, investors already feel like they have lost money because they missed out on buying earlier. If they buy now, they would “realise” that perceived loss. If they do not buy, then they remove the possibility of losing money – loss aversion. They would not lock in the perceived loss, and they can have the hope that one day they can buy it lower if markets fall.

This begs the question – will markets continue to rise? It baffles me that after almost 30 years in the market, I still observe that while human beings are terrible at forecasting the future, everyone who invests is eager to predict the markets’ future direction with no accountability at all.

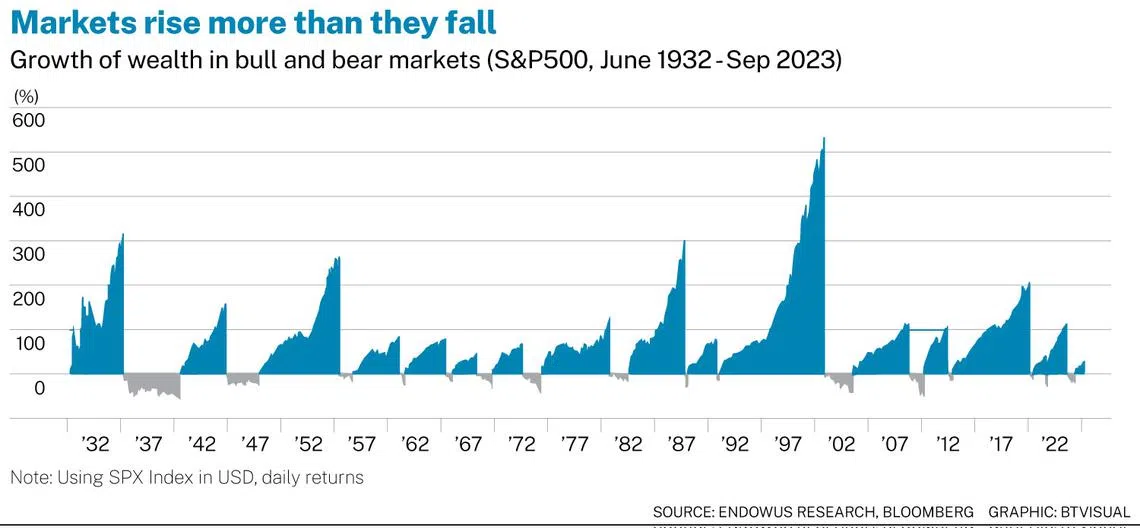

I would focus on the weight of evidence from a long history of financial markets. History teaches many lessons. One is that markets tend to go up more frequently and for longer than people think. The times when markets fall are fewer than people expect. In most cases, the decline is over before you know it; most of the time, it is over when people are most bearish or negative.

We’ve just witnessed some of the most unprecedented or rare occurrences in the history of financial markets. Statistically, it is very rare for the equity and fixed income markets to both decline in a calendar year; 2022 was one of those years. For both to go down and end the year with negative returns in the double digits is almost unheard of.

It is also rare for the fixed income market to show negative returns for two consecutive years.

This happened in 2021 and 2022, based on the Bloomberg Global Aggregate Index. It has never chalked up a third year of negative returns in modern history. Yet for a good part of this year, it was in negative territory. In terms of probabilities, we are more likely to end the year in positive territory for fixed income, but who knows?

Again, bear markets in equities – defined as a fall of 20 per cent or more – are rare in a given year. It normally happens around a crisis or an economic recession.

However, we have just gone through a unique period; we have had a decline of more than 20 per cent in three of the past five years in equity markets. In 2018, when the US Federal Reserve started hiking rates, global markets fell around 20 per cent and rebounded strongly in 2019.

In 2020, during the Covid crisis, markets dropped precipitously by more than 30 per cent in just over a month before quickly rebounding and making new highs in 2021. In 2022, worried by inflation and spiking interest rates, equity markets fell by well over 20 per cent throughout the year.

Of course, hindsight is 20/20. History tells us that predicting short-term market movement is futile effort and impossible to get right. However, if there is any time to invest, it is definitely after a fall of more than 20 per cent. The probability of the market falling further versus rising back up is certainly going to be in your favour.

Looking at those recent examples: after the 2018 fall, we had a strong 2019. After the Covid crash in early 2020, the market surged and made new historic highs in 2021. After 2022, we’ve had a strong rebound in 2023. This pattern holds at any point in the history of financial markets.

Financial markets have always skewed positively, which means that over time they move to the right, on an upward trajectory, and are expected to hit a new high over time.

This isn’t a flat or zero-sum game; the market is, like many things in the world and in life, an infinite-sum game. Yet, even if we know history and probability, our emotions and psychological biases will work to prevent us from making the right decision.

This is why we suggest having a regular savings and investment plan, and sticking to that plan despite what markets do in the short term. These systems and plans such as dollar-cost averaging are put in place to remove emotions from the decision-making process.

It doesn’t matter whether markets are up or down; we stick to the plan and the markets will generate the long-term returns. Removing biases from our behaviour is an important stepping stone to long-term investment success.

The writer is co-founder and chief investment officer, Endowus, an independent wealth platform advising over S$6 billion in client assets across public, private markets and pensions (CPF and SRS)

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Share with us your feedback on BT's products and services