How soaring childcare costs are crushing New Yorkers

NOT long after Crystal Springs started her new job at a large insurance company in midtown Manhattan this year, she realised that a much bigger chunk of her pay cheque than she expected was going directly to childcare for her five-year-old daughter.

Springs had dreamed that the job, which allowed her and her husband to make about US$200,000 a year combined, would help provide a comfortable middle-class life for her family in Ozone Park, Queens. But as bills mounted and her daughter’s routine days off turned into emergencies, she felt stuck. Exasperated, she left the job she had fought so hard to get.

About the same time, in the Castle Hill section of the Bronx, Doris Irizarry was struggling to sustain the daycare centre she ran out of her home. Expenses were rising every month, and she said she was making only about US$3 a day for each of the six children who attended. She finally closed for good this summer after 25 years.

“This industry is going to die,” she said. “We cannot survive without the parents, and the parents cannot survive without us. We’re a unit.”

In a notoriously stratified city experiencing its worst affordability crisis in decades, the skyrocketing cost of childcare is one of the few issues that connects working families across geography, race and social class.

All but the wealthiest New Yorkers – even the upper-middle class and especially mothers – are scrambling to afford care that will allow them to keep their jobs. Median prices for nearly every type of childcare in New York City have shot up since 2017, according to state surveys of providers. Montessori preschool programmes can cost more than US$4,000 a month in affluent neighbourhoods, and working-class families are stretching their budgets to pay at least US$2,000 a month for daycare.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

And the workers who provide childcare are reeling from high costs and are leaving the industry. Many make just over minimum wage, leaving them barely able to afford to stay in New York City or pay for care for their own children.

Interviews with more than three dozen parents, nannies, daycare providers and experts revealed a potentially devastating crisis for the future of New York City.

In recent years, only the astronomical cost of housing has presented a greater obstacle to working families than the cost of childcare, experts said.

A New York City family would have to make more than US$300,000 a year to meet the federal standard for affordability – which recommends that childcare take up no more than 7 per cent of total household income – to pay for just one young child’s care. In reality, a typical city family is spending over one-fourth of their income to pay for that care, according to the US Department of Labor.

Although families and providers across the country face the same issues, few cities confront affordability challenges as profound as New York’s. In a city where a second income is all but required for most families, soaring costs strain a patchwork childcare system made up of daycare centres in family homes, preschool and after-school sites in public school buildings and nannies working in private apartments.

“If people can’t go to work knowing your child is safe and not break your financial back to do it, then people can’t be here,” said Richard Buery Jr, CEO of the Robin Hood Foundation, a charity focused on fighting poverty in New York City. “If people can’t be here, they can’t pay taxes; and if people can’t be here, employers won’t be here.”

More than half of New York City families are spending more than they can afford on childcare, including both lower-income and higher-income families, according to a recent study by Buery’s organisation.

Families leaving the city

The long-term consequences for the health of the city are only beginning to be felt, but it is clear that there is a profound economic cost. Parents leaving New York or cutting work hours because of childcare cost the city US$23 billion in 2022, according to the city’s Economic Development Corporation.

New York is losing families with young children. Between 2019 and the end of 2022, there was a significant drop in the number of families with children younger than five living in the city, according to a recent analysis by New School researchers.

Data has shown that Black families in particular have left in significant numbers, citing concerns about affordability. The city has also seen a sharp decline in its public school population.

Brittany Dietz and her husband were not planning to leave when they started researching daycare centres near their home in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. They considered hiring a nanny or sharing a nanny with another family to reduce costs. Dietz, who works in advertising, was not impressed with the options, some of which would have amounted to a second rent. The cost of raising a child in New York helped persuade her and her husband to make their recent move to Cleveland, Dietz’s hometown.

There, she found six daycare centres near their new home, all with space for her 18-month-old, and chose one that costs about US$50 a day. Moving, she said, has “opened up a world of possibilities” for her family.

“Nothing really pushes you to leave the city until you have a kid,” she said. “If we could have made it work, we probably would have stayed.”

A burden on mothers

In interviews, several parents whose combined household income was US$200,000 a year or more said nannies or daycare ranked second on their monthly budget, after rent or mortgage. Many said they were unsure if they would stay in the city if they had a second child, especially those without family nearby to help with babysitting.

One family that earns more than US$400,000 began making preliminary plans to leave the city after finding a daycare in their Williamsburg, Brooklyn, neighbourhood that would cost over US$4,700 a month for one of their children to attend full-time in the fall of 2024.

The burden has fallen especially hard on mothers, many of whom said they had cut back their work hours, moved jobs to have more flexibility to work remotely or stared in disbelief at budgeting spreadsheets that showed well over half – and in some cases nearly all – of their monthly take-home pay going to babysitters or daycare centres.

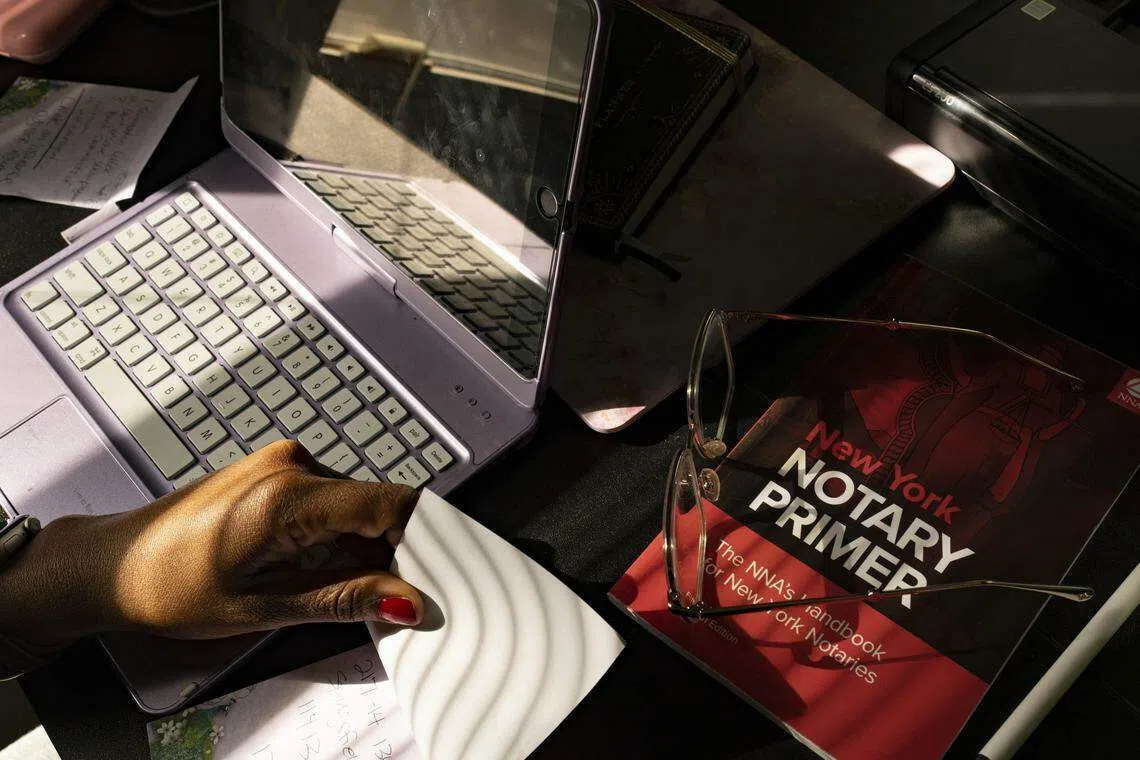

“I found myself apologising for having to be a mother,” Springs, who is now building her notary business, said of her time at the insurance company.

Her first week at that job coincided with her daughter’s school vacation, and she sensed her boss’s mounting frustration as she kept asking to work from home.

Some daycare providers said they were deeply sympathetic to the parents they served and have created sliding-scale programmes for some families who were struggling to pay daycare costs.

Silvia Reyes, a full-time nanny, was making US$19 an hour working for a family when she started eight years ago. Since then, everything in her life has gotten more expensive even as she has become the sole financial provider for her mother, her teenage brother and her toddler. Her rent in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, is about US$2,000 a month and is set to rise again.

She asked the family she works for in Park Slope, Brooklyn, for a raise to US$33 an hour, and they agreed. But even that rate, which is more than many other nannies receive, will not cover the cost of full-time daycare, added Reyes, who is a member of a childcare worker cooperative at the Carroll Gardens Association, a neighbourhood advocacy organisation.

She has set aside her hopes of having her son socialise with other children during the day, and he now stays at home with his grandmother while Reyes is at work.

“I can’t have the luxury of sending my kid to a daycare if it would cost more than my rent,” she said. “If I don’t get paid well, I can’t afford living here and I can’t afford having my baby and my mom and my brother, and I have to look for another job.” NYTIMES

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Share with us your feedback on BT's products and services