Ten lessons from a history of disruptions

There are many common reasons how and why business disruptions happen, and are resisted

[SINGAPORE] Disruption has felled many once-great companies, including Digital Equipment, Nokia, Sears, Kodak, Blockbuster, Borders as well as several newspapers and brick-and-mortar retailers across the world.

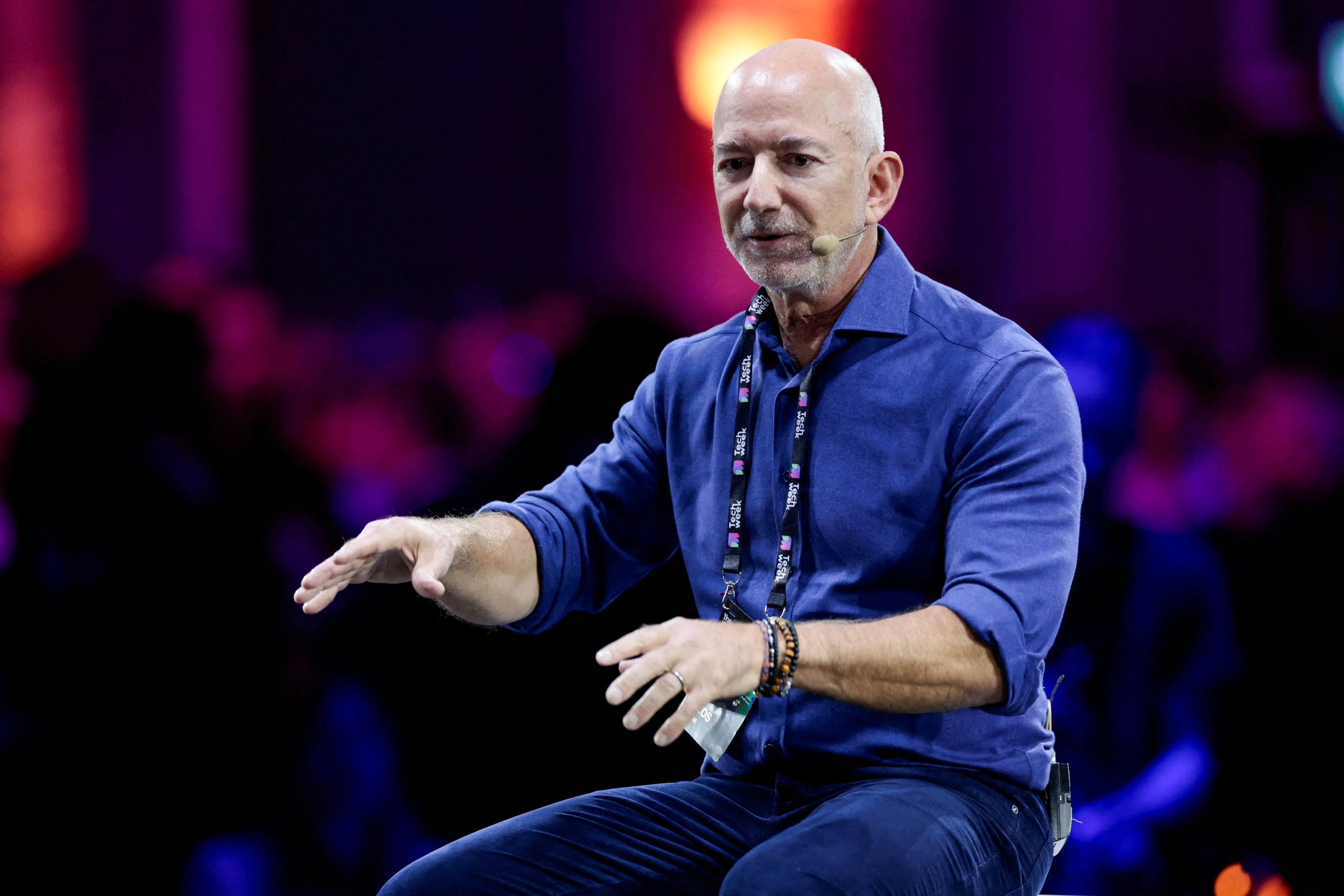

In his new book, Epic Disruptions, Professor Scott D Anthony, a professor of strategy at Dartmouth College in the US, chronicles how a variety of disruptions down the centuries have reshaped industries and societies.

Having worked as a consultant with Professor Clayton Christensen, the pioneer of the study of business disruption, and ranked among the top 10 most influential management thinkers by Thinkers50, he brings both academic and practical experience to trace the history of disruptions, from the printing press to generative artificial intelligence. Here are 10 lessons from that history, based on both the book and my conversation with Prof Anthony:

Market leaders usually see a disruption coming, but don’t act

There are both rational and irrational reasons for this. The rational reason is that it makes more sense to run their existing business better, instead of disrupting it when a new challenge emerges. The irrational reason is fear, worry and struggles, often rationalised as “maybe this time it will be different, maybe I will be immune to this”.

Nokia was a case in point. When Apple’s iPhone was launched in 2007, Nokia, which was the market leader in mobile phones with around one billion customers, thought it was unassailable.

It saw the iPhone as a niche, expensive product that lacked key features such as a removable battery and a physical keypad and did not have a variety of models. What it missed was that the iPhone was not just a product but an ecosystem, which made it a software platform and a computing device.

Navigate Asia in

a new global order

Get the insights delivered to your inbox.

“Ghosts” haunt every organisation

Drawing on Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, Prof Anthony suggests that every organisation is haunted by ghosts of the past, present and future.

Ghosts of the past are invoked when leaders of organisations say: “We tried that before and it didn’t work.” Ghosts of the present are evidenced by the statement: “This – not that – is the way we do things around here,” while ghosts of the future come into view when leaders point out: “If we move from this state to that state, we might lose our jobs.”

Disruption is not necessarily technological

We often view disruption as being a technological phenomenon. But Prof Anthony reminds us that there have been several disruptions that were not. He explains, for instance, how Florence Nightingale revolutionised nursing in the 19th century. During the Crimean War, she used data to show that more soldiers died from preventable diseases than from battle wounds because of poor sanitary conditions in hospitals.

Emphasising prevention and not only treatment, her work led to the redesign of health facilities and sanitation reforms in public health, which dramatically reduced mortality rates and transformed healthcare.

In recent years, Taylor Swift has disrupted the music industry. Lacking ownership of her music, which was originally owned by record labels, she re-recorded new versions of it, which had the double benefit of making money off the re-recordings and providing new music for her fans.

She also communicates with her fans on social media, where she hints at future releases, invites selected fans to private listening parties and even stages unexpected appearances, including at fan weddings. Swift pioneered a new route to musical stardom.

Prof Anthony cites DBS Bank as another disrupter. It has not developed any new technology, but has used technology to transform its business model in ways far beyond what most other banks have been able to do.

For instance, it has partnered widely with non-banks in areas such as e-commerce, travel and ride-hailing, deployed artificial intelligence (AI) across hundreds of use cases, created connectivity with other payment networks, such as Alipay and QR codes, and was one of the first banks in the world to create an exchange to enable the trading of digital assets.

Chinese companies such as ByteDance, Kuaishou and Tencent have disrupted the movie business through “micro-dramas”, typically made up of short episodes of one to five minutes, with the whole series adding up to roughly the length of a conventional feature film.

Viewers, now numbering hundreds of millions, have been hooked by the format, which has also become a major cultural export. This is another example of how business model innovations can also be disruptive.

“First mover advantages” are overrated

Products that come out first are usually not the biggest winners. Facebook was preceded by Friendster and Myspace. Google was the 18th venture-capital-funded search engine. Among MP3 players, Apple’s iPod came after the Rio Diamond and Creative Technology’s Nomad, both of which predated the iPod by more than two years.

The latecomers were able to correct many of the pioneers’ mistakes – for example by improving the user experience (Apple and Facebook), deploying better technical and business architecture (Google) and timing their scale-up to when elements of the Internet ecosystem, such as broadband and more advanced hardware, could support mass adoption (Apple). Something similar may happen with AI.

Some AI incumbents, too, will be disrupted

What most leaders in AI are doing now is following a technological approach, according to Prof Anthony. This is not that difficult to copy, although it requires massive funding. So, for example, OpenAI took the lead in launching a large language model (LLM), and then Google, Meta, Microsoft, Anthropic and others soon followed.

So far, nobody has figured out how to make money from LLMs – costs, which increase with every new user and indeed, every new query, far exceed revenues. So long as this continues, it will be a technological race that will favour whoever has the most money. But when some company figures out a viable business model, that’s when things will get interesting. It may be one of the incumbents, but it may also be another company, which will disrupt the incumbents.

Many disruptions happen when different pieces click

In his book, Prof Anthony points out that “disruption rarely traces to a single big-bang invention moment”. Rather, it is the result of combinations of innovations that came before, sometimes centuries earlier. As he puts it, “magic happens at intersections”.

The printing press, invented by Johannes Gutenberg in 15th-century Germany, disrupted older, slower and more tightly controlled systems for spreading knowledge, religion and ideas.

The components that made up the printing press were not new. Ink and paper had already been invented centuries before and were combined in the form of stamps on paper. Movable type was conceived in China 400 years earlier. The screw press, which involved two plates pressed together with an object in between, had also been invented. But the combination of the screw press, movable type, ink and paper into a device that could speed up mass printing was totally new.

Before the iPhone was launched in 2007, mobile phones already existed, as did mobile web access via WAP browsers and portable digital music.

The touchscreen had been created in the 1980s by Xerox. Corning had developed scratch-resistant “gorilla glass”. Apple integrated these innovations into a phone-cum-computing device.

LLMs were the culmination of a series of innovations over decades in AI, software and computing, including advances in machine learning and natural language processing, as well as chip technology, which led to the graphics processing units that power LLMs.

Disruptions are often not immediate successes

Gutenberg’s printing press took more than 10 years of experimentation to arrive at a proof of concept. The transistor displaced vacuum tubes in telecommunication networks only after decades of development. The iPhone was not an immediate success – it was not until the App store came along that it took off. Work on disposable diapers, which Prof Anthony describes as a disruptor in baby care, started in 1956, but the product was only successfully launched in the 1970s.

Disruptors often show a willingness to be misunderstood

Explaining his company’s long-term orientation, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos told shareholders in 2011: “We are willing to be misunderstood for long periods of time.”

Founded in 1994, Amazon reported its first full-year profit only in 2003, having focused more on growth than profitability. Many analysts criticised Amazon for this and even predicted it would go bankrupt, but Bezos ignored them. Again, when it launched Amazon Web Services (AWS) in 2006, some analysts were sceptical, seeing this as a distraction.

But Bezos remained unmoved and, by 2016, AWS had generated US$10 billion in profitable revenue, which soared more than 10-fold to over US$100 billion in 2024.

Ride-hailing pioneer Uber was unprofitable for 14 years after its founding in 2009. Procter and Gamble (P&G) persisted with Ivory soap – launched in 1879 and advertised as “the soap that floats” – for 15 years before it succeeded and became P&G’s first blockbuster brand.

Prof Anthony points out: “Never has there been an idea that was perfect from day one and was executed cleanly.” Disruptive innovations often involve continuous learning and making course corrections along the way, but the vision of working on a problem that matters to the consumer remains fixed.

Consumers may sense what they want, innovators show them

Apple co-founder Steve Jobs famously said: “Consumers don’t know what they want until you show them.” Is that true? Prof Anthony’s answer is “yes and no”.

Consumers can be very articulate about the problems and frustrations they are facing with a product. For example, consumers could have told Jobs before the iPhone: “It’s frustrating that I have a phone and a computer but I can’t bring them together and I can’t do computing when I’m on the go.” But bounded by what they know, consumers cannot envision the future.

It takes a disruptive innovator to resolve the problems they face. Thus, focus groups, which many companies use to help them innovate, tend to provide consensus around today’s products. They are not reliable guides to what tomorrow’s products could be.

Anomalies can be triggers for disruptions

Anomalies are things you don’t expect – the surprises. “That’s often where learning comes from,” says Prof Anthony. For instance, it’s what a young person in an organisation says that sounds crazy, or the business model, which, when you see it for the first time, you say: “I would never do that.”

Airbnb is an example – allowing a stranger to sleep in a spare room. Or getting into a car that has no driver. It just doesn’t sound right the first time you hear it. But that’s where a lot of innovation and disruption come from.

Epic Disruptions by Scott D Anthony (Harvard Business Review Press) is available at Kinokuniya Books and on Amazon.sg

Decoding Asia newsletter: your guide to navigating Asia in a new global order. Sign up here to get Decoding Asia newsletter. Delivered to your inbox. Free.

Copyright SPH Media. All rights reserved.